Copyright 2013 by Alexander Lee

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies. Originally published in Great Britain by Hutchinson, a division of the Random House Group Limited, London, in 2013.

www.doubleday.com

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Book design by Michael Collica

Jacket design by John Fontana

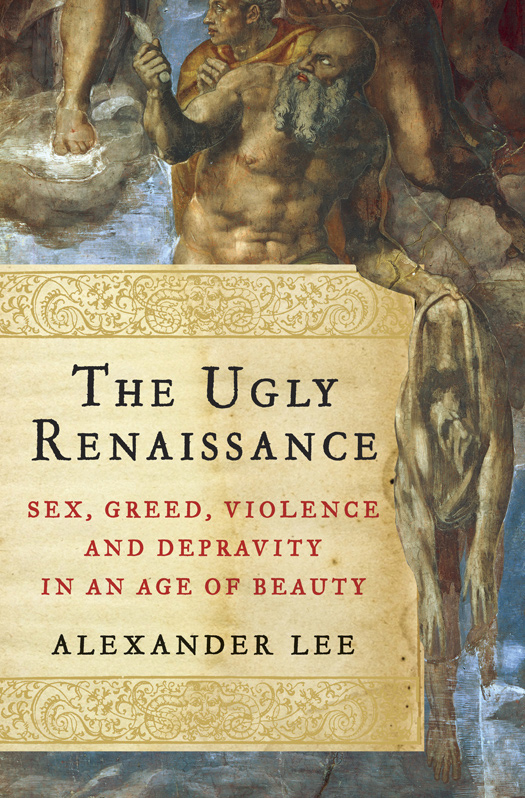

Front-of-jacket painting: Last Judgement, detail of Saint

Bartholomew by Michelangelo/Scala/Art Resource, NY

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lee, Alexander (Historian)

The ugly Renaissance / Alexander Lee. First American edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. RenaissanceItaly. 2. ItalySocial life and customsTo 1500.

3. DegenerationSocial aspectsItalyHistoryTo 1500.

4. ItalyCivilization12681559. I. Title.

DG 445. L 44 2014

945.05dc23

2013015480

ISBN 978-0-385-53659-2 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-0-385-53660-8 (eBook)

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

First American Edition

v3.1

For

James and Robyn OConnor

and

Pit Pport and Marian van der Meulen

with much love and best wishes for their future together

AUTHORS NOTE

It is necessary to address a few questions of method.

First, a note on geography. This book concentrates exclusively and unashamedly on the Renaissance in Italy, and I am conscious that this geographical focus may be subject to some reasonable question. There was, after all, no Italy before 1871, and though humanists such as Petrarch did have a certain concept of what Italy meant, the notion was fairly amorphous. On the one hand, boundaries of any kindleast of all the hard-and-fast borders beloved of modern political debatesimply did not exist, and that which contemporaries might have thought Italian in some vague way quickly shaded off into other species of identity, particularly in places like Naples, Trent, and Genoa. On the other hand, even within those territories that might be defined as certainly Italian, the existence of dialects (there was, after all, no such thing as the Italian language yet), independent statelets, and strong local loyalties makes any geographical generalizations somewhat dangerous. This is particularly true when it comes to the great North/South divide, a division that is so intense it continues to dominate Italian political debate today but is no less troublesome when applied even to the states of early Renaissance Tuscany, for example. Yet despite these reservations, it is possible to talk of Italy in relation to the Renaissance with some degree of useful meaning. As scholars have readily acknowledged, the cultural developments that occurred in the Italian peninsula (broadly conceived) between ca. 1300 and ca. 1550 do indeed seem to have certain common features that stand apart from the culture of the rest of Europe and that justify talk of Italy in this context. I cannot help but suspect that Renaissance humanists of Petrarchs stripe might have approved, if not on scholarly grounds, then at least for emotive reasons.

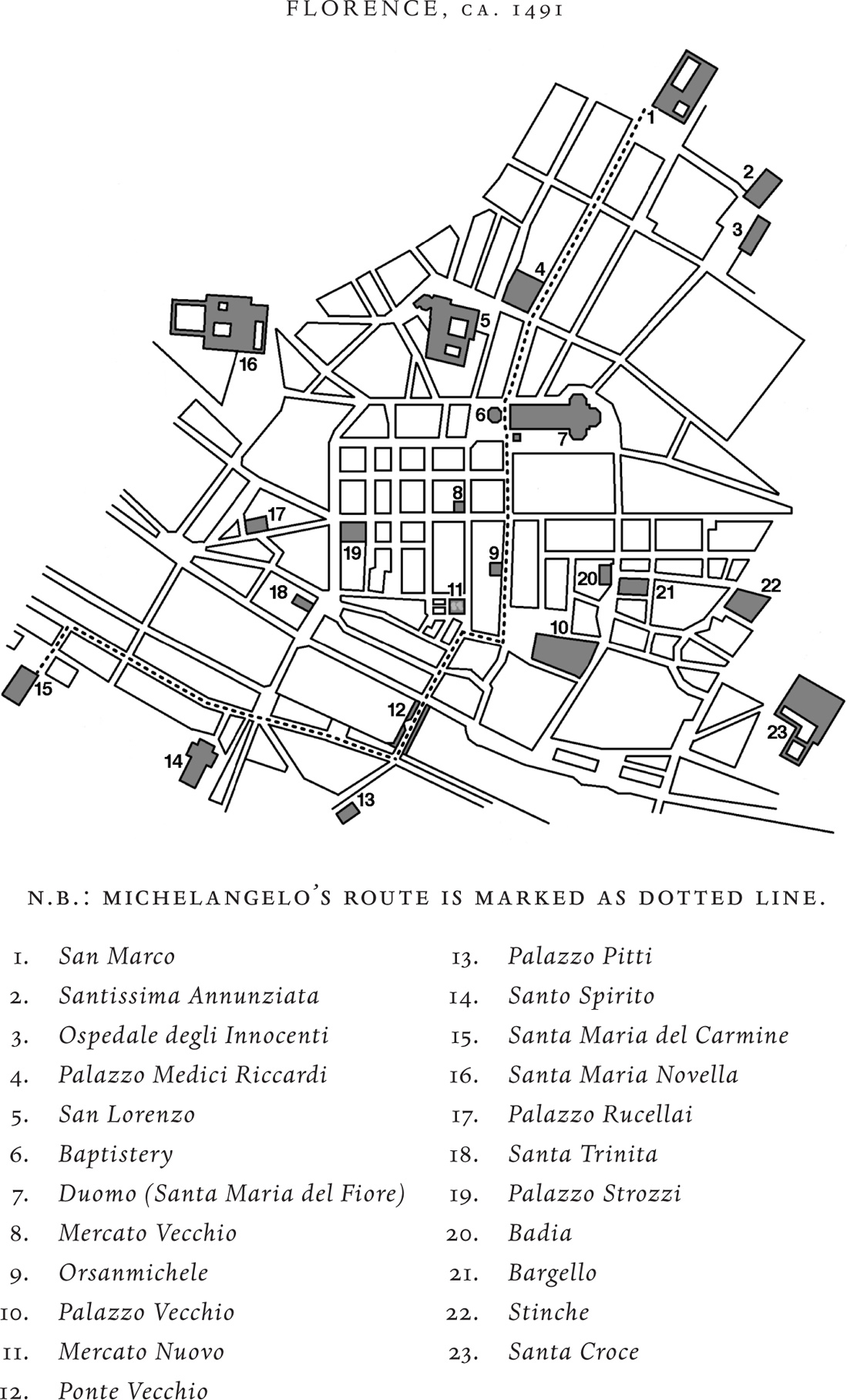

Having set out my Italian stall, I must point out that this book focuses most heavily on two or three major citiesthat is, Florence, Rome, and (to a lesser extent) Urbino. This is not to say that other centers do not get a look in. Venice, Milan, Bergamo, Genoa, Naples, Ferrara, Mantua, and a whole host of other cities all appear in the narrative where appropriate, and it would certainly not be accurate to pretend that the Renaissance did not touch every single town and city in Italy to one extent or another. But the focus on Florence, Rome, and Urbinowith a particular accent on Florenceis, I think, justified on two main grounds. First, Florence constitutes the historical and spiritual home of the Renaissance as a whole. Both contemporaries and modern historians have generally agreed that it was in Florence that the Renaissancehowever we might wish to define itbegan and grew to maturity. In their different ways, and to very different degrees, Rome and Urbino constituted major focal points for artistic and literary endeavor, albeit at a later stage. Second, any narrative has to have some measure of order, and a completely comprehensive study that showed no more favor to one city than another would be both inaccurate and unwieldy.

Second, a note on chronology. Anyone with even a passing knowledge of the subject of this book will be aware of how enormously difficult it is to put dates on the Renaissance. Given how very troublesome it has proved to define what the Renaissance actually was, it is perhaps unsurprising that historians have agonized not only over where the termini of the period lie but also over whether it is useful to think of it in terms of a period (in the true sense) at all. The chronological bounds I have chosen to use for this bookthat is, the years between ca. 1300 and ca. 1550are not intended to be either authoritative or definitive, but instead reflect the general sense of scholarly consensus and are meant simply to give a measure of structure to what is already a complex enough series of phenomena. I will not deny that such vagueness is rather ugly, but since it is something that all Renaissance historians have to deal with at some stage, I cant help but feel it is just one more example of why the ugly Renaissance is with us all in one way or another.

Introduction

B ETWEEN H EAVEN AND E ARTH

G IOVANNI P ICO DELLA Mirandola (146394) lived deep and sucked all the marrow out of life. There was nothing that did not interest and excite him. Having mastered Latin and Greek at an unfeasibly young age, he went on to study Hebrew and Arabic in Padua while still in the first flower of youth and became an expert on Aristotelian philosophy, canon law, and the mysteries of the Kabbalah before he was out of his twenties. Surrounded by the art of Brunelleschi, Donatello, and Piero della Francesca in Florence and Ferrara, he became a close friend of many of the most glittering stars of his day. A cousin of the poet Matteo Maria Boiardo, he was an intimate acquaintance of the enormously wealthy litterateur Lorenzo de Medici, the classical scholar Angelo Poliziano, the Neoplatonic trailblazer Marsilio Ficino, and the firebrand preacher Girolamo Savonarola. He was, moreover, a writer and a thinker of breathtaking originality. Quite apart from penning a multitude of charming verses, he dreamed of uniting all the various branches of philosophy into a single, inspiring whole and longed to bring the religions of the world together.