STERLING and the distinctive Sterling logo are registered trademarks of

Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Available

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Published by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

387 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016

Published by arrangement with Oxford University Press, Inc.

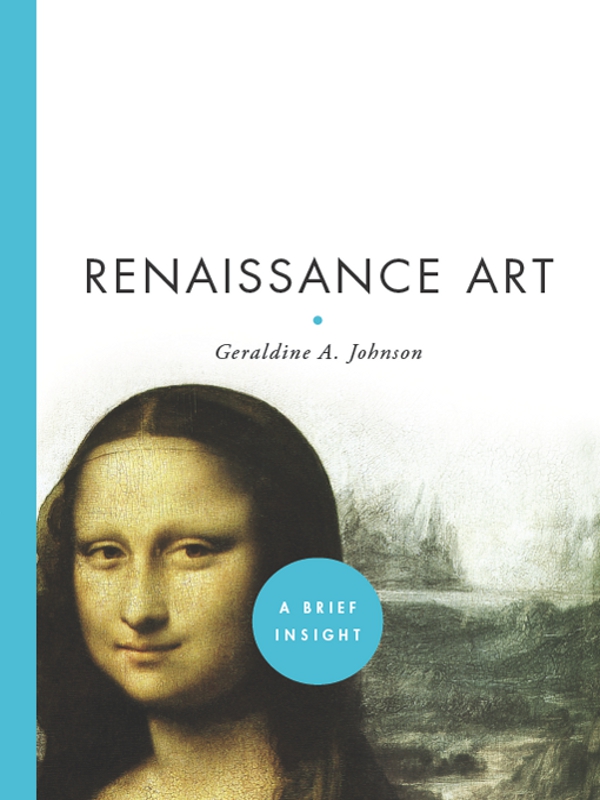

2005 Geraldine A. Johnson

Illustrated edition published in 2010 by Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Additional text 2010 Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

Distributed in Canada by Sterling Publishing

c/o Canadian Manda Group, 165 Dufferin Street

Toronto, Ontario, Canada M6K 3H6

Book design: The DesignWorks Group

Please see picture credits on page 183 for image copyright information.

Printed in China

All rights reserved

Sterling ISBN 978-1-4027-7540-6

For information about custom editions, special sales, premium and corporate purchases, please contact

Sterling Special Sales Department at 800-805-5489 or .

Frontispiece: Detail of Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors, oil on panel, 1533.

RENAISSANCE ART

Geraldine A. Johnson

New York / London

www.sterlingpublishing.com

To Chris, my Renaissance man

CONTENTS

FOR THEIR HELP AND SUPPORT while planning and writing this book, I would like to thank my fellow students at Christ Church, Oxford, and especially my colleagues in the Department of History of Art at the University of Oxford. Staff and colleagues in the History Faculty and the Sackler Library in Oxford were also invaluable in completing this volume, as were my editors at Oxford University Press, Marsha Filion and Katharine Reeve, and my copy editor, Alyson Lacewing. This new edition by Sterling Publishing has benefitted greatly from Rebecca Springers picture research. My graduate students at Oxford served, perhaps unwittingly, as guinea pigs on which to test some of the ideas presented here, for which I am very grateful.

My wise and wonderful parents, R. Stanley Johnson and Ursula Gustorf Johnson, have always been my greatest champions. In the case of the present book, they were also the first to read the manuscript and very kindly provided a key illustration, both reflections of their own deep appreciation and understanding of art. My family and friends, both near and far, gave me much enthusiastic support during the preparation of the original Oxford University Press volume and this new Sterling Publishing edition. I am especially thankful to: Gregoire and Kristine Klees-Johnson; Doris and Hans Schmeling; Peter, Judy, Sarah, and Jane Martin; Tatiana String; and my lively nieces and nephews in Oxford and Chicago. The arrival of my two beloved daughters, Olivia Beatrix and Isabelle Rosamund, since the original edition of this book was published has provided renewed inspiration and countless moments of joy. Last but certainly not least, my amazing husband, Chris Martin, was absolutely crucial to my completing this volume, not only by providing much love and encouragement, but also by patiently listening to my latest half-baked ideas for the text and making sure that a steady supply of high-energy snacks was available while it was actually being written. It is to him, a true Renaissance man for the twenty-first century, that I dedicate this little book con tantissimo amore.

Raphael Sanzio, The Sistine Madonna, oil on canvas, c. 151214.

ONE

Introduction: Whose Renaissance?

Whose Art?

Art in the Renaissance

The year is 1768. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, at the time a mere law student, but soon to become Germanys most famous poet-philosopher, steps into Dresdens new art museum for the first time and describes the scene:

the profound silence that reigned, created a solemn and unique impression, akin to the emotion experienced upon entering a House of God, and it deepened as one looked at the ornaments on exhibition which, as much as the temple that housed them, were objects of adoration in that place consecrated to the holy ends of art.

One of the works he would have admired was Raphaels Sistine Madonna (page viii), acquired in 1754 by Dresdens ruler, Augustus III of Saxony, but familiar to us today from countless Christmas cards, posters, and knickknacks featuring the paintings cherubic pair of plump child-angels. For Goethe, seeing such works in the hushed atmosphere of Dresdens picture gallery was a quasi-religious experience in which paintings were worshipped as the aesthetic relics of semi-divine artistic geniuses. Still today, when we gaze reverentially at paintings, sculptures, and drawings by Renaissance masters such as Raphael displayed in the temple-like surroundings of art museums, we continue to treat them like objects worthy of aesthetic worship and almost mystical visual contemplation.

The Sistine Madonnas original 16th-century beholders, however, did not see religion merely as a kind of metaphor for the appreciation of art, but rather encountered such paintings within the context of actual religious rituals. For the Sistine Madonna was not really a work of art as Goethe or, indeed, any of us today would understand the term. Instead, it was first and foremost a devotional image with very specific ritual purposes. It was, in short, an .

We will be considering the altarpiece as a objects with carefully selected iconographies produced for defined sacred or secular purposes that had evolved from venerable and often still-ongoing traditions. At the same time, it is precisely during the Renaissance that the modern concept of Art (with a capital A) first began to emerge, together with related notions about the status of the artist as creative genius, the importance of originality (rather than craftsmanship) in assessing the merit of art objects, and the significance of using aesthetic criteria to judge works of artsubjects that we will consider briefly below and, at greater length, in several of the following chapters.

Reconsidering the Renaissance

However, it is not only the term Art that we need to consider carefully. In fact, the first part of this volumes title, Renaissance, is also more complex than may appear at first glance. The word literally means rebirth, but has come to be associated more generally with revival and innovation, often in a variety of fields of endeavor. So, for example, we speak of the Harlem Renaissance when describing the new flourishing of art, music, dance, and literature in New York Citys African-American community in the 1920s, while everyone from Benjamin Franklin to Apples Steve Jobs has been called a Renaissance man thanks to having multifaceted interests and innovative ideas.

Next page