Harlem Renaissance Artists and Writers

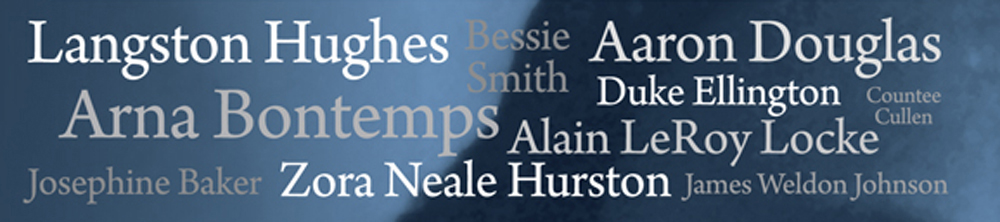

Harlem, New York in the early 1920s and 1930s was the backdrop for an outpouring exploration if black identity through music, writing, poetry, and social commentary. This period in history became known as the Harlem Renaissance. Ignited by a great migration from the rural South to the industrial North, the Harlem Renaissance celebrated the unique aspects of African- American culture and attracted audiences throughout the world.

About the Author

Wendy Hart Beckman is an award-winning freelance writer, editor, college instructor, and corporate writer. She has published over 250 freelance articles in regional and national magazines and newspapers, and has received 13 awards for her writing. Some of her other published books for Enslow Publishers Inc. include National Parks in Crisis: Debating the Issues and Robert Cormier: Banned, Challenged, and Censored.

In the early 1900s, there arose a remarkable period of creativity in the black community centered in the Harlem section of New York City. African-American art, literature, music, and social commentary flourished during the 1920s and 1930s. Attracting both black and white sponsors and audiences, this cultural movement became known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Sterling Brown [a Renaissance writer], has identified five themes animating the movement: (1) Africa as a source of race pride, (2) black American heroes, (3) racial political propaganda, (4) the black folk tradition, and (5) candid self-revelation.

At the core of the Harlem Renaissance was a group of older African Americans from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the National Urban League (NUL), and various universities and journals. Around this group were the writers and artists who represented the young heart and soul of the New Negro movement. In addition, there was another group made up of other writers and artists who participated at various times but were not pivotal to the movement.

W.E.B. Du Bois, the influential editor of the NAACP magazine The Crisis, coined the term Talented Tenth, referring to the elite tenth of a percent of the black community. The Talented Tenth was one of the major forces of the Harlem Renaissance.

According to historian David Levering Lewis, two things made the Harlem Renaissance possible: demography and repression. A great black migration had begun from the rural South to the industrial North as African Americans sought new jobs and new freedom. Racial tensions rose and race riots occurred across northern cities in 1919.

The Talented Tenth of Harlem reacted by seeking to create the image of the New Negro. The founding fathers of the Harlem Renaissance realized that blacks access to commerce, politics, and property was blocked. Two paths remained opened to them: arts and letters. There were, however, opposing forces within the Harlem Renaissance with differing philosophies as to the role of black art and literature. Although many of the writers and artists did not share a common purpose, their work all reflected black life from a black point of view.

There were three major phases of the Harlem Renaissance. The first phase, which ended around 1923, was highly influenced by white artists and writers who were interested in black culture.

The second phase, from about 1924 to 1926, began when more blacks began to express their creativity and philosophy themselves. The NUL and the NAACP and their magazines, Opportunity and The Crisis, dominated this phase. Both these organizations believed that arts and letters were only good as propaganda tools for the advancement of blacks. The second phase also marked collaboration between the Talented Tenth and the white Negrotarians (as writer Zora Neale Hurston called them).

The third phase, from mid-1926 to March 1935, was dominated by what Hurston called the Niggeratiprolific black writers and artists. This last phase marked a rebellion against the civil rights leaders and pushed art for arts sake.

During the Renaissance, Harlem became the place to see and be seen. Langston Hughes, a leading Renaissance writer, described the atmosphere in his first autobiography, The Big Sea:

It was the period when the Negro was in vogue.... But I thought it wouldnt last long.... For how could a large and enthusiastic number of people be crazy about Negroes forever? But some Harlemites... thought the race problem had at last been solved.... They were sure the New Negro would lead a new life from then on in green pastures of tolerance.... I dont know what made any Negroes think thatexcept that they were mostly intellectuals doing the thinking.

To celebrate the voices of this new Harlem creative movement, the NAACP threw a benefit party. There Langston Hughes met the influential Charles S. Johnson, editor of the NULs new magazine Opportunity. Mr. Johnson, I believe, did more to encourage and develop Negro writers during the 1920s than anyone else in America, said Hughes. Jessie Fauset at The Crisis, Charles Johnson at Opportunity, and Alain Locke in Washington were the three people who midwifed the so-called New Negro literature into being.

In 1924, Charles S. Johnson threw a party at New York Citys Civic Club. He invited a group of influential white writers, editors, publishers, and businessmen to introduce them to a comparable group of equally talented African Americans. Such a mingling between the races was virtually unheard of at the time. Johnson believed that the white publishing world knew very little about the wealth of talent among blacks. The exchange was phenomenal and electrified the African-American literary community. Suddenly it became fashionable to be an African-American artist.

In 1931, at the funeral of ALelia Walker, a famous black party hostess, Langston Hughes noted, That was really the end of the gay times of the New Negro era in Harlem, the period that had begun to reach its end when the crash [Great Depression] came in 1929 and the white people had much less money to spend on themselves, and practically none to spend on Negroes, for the depression brought everybody down a peg or two. And the Negroes had but few pegs to fall.

The Harlem riot of March 19, 1935, brought the Renaissance to an end. As a result of tensions leading to boycotts and picketing, violence erupted after a young boy was beaten for shoplifting. Three people were killed that night, and $2 million worth of damage was done.

It is difficult to quantify the effect of the Harlem Renaissance, but one can start by looking at what was produced during this period. In the area of literature alone, twenty-six novels were written as well as ten volumes of poetry, five Broadway plays, numerous nonfiction books, essays and short stories, and three performed ballets. This was in addition to the contribution of artistic works in the form of musical compositions, concerts, paintings, sculptures, murals, and photographsan amazing record of creative accomplishment!

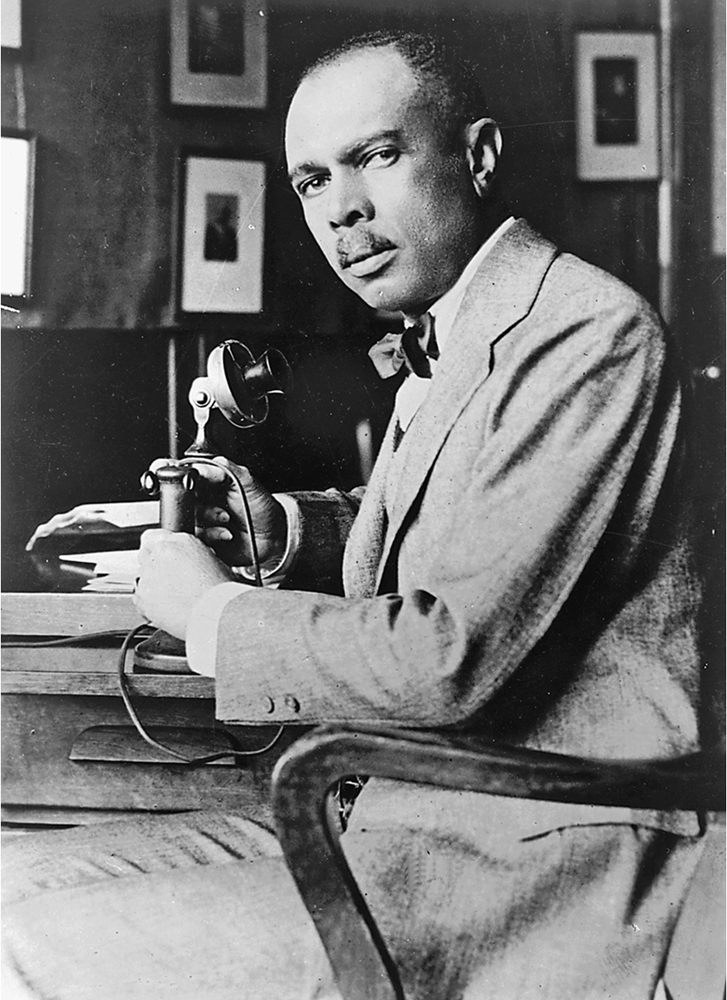

Image Credit: Library of Congress

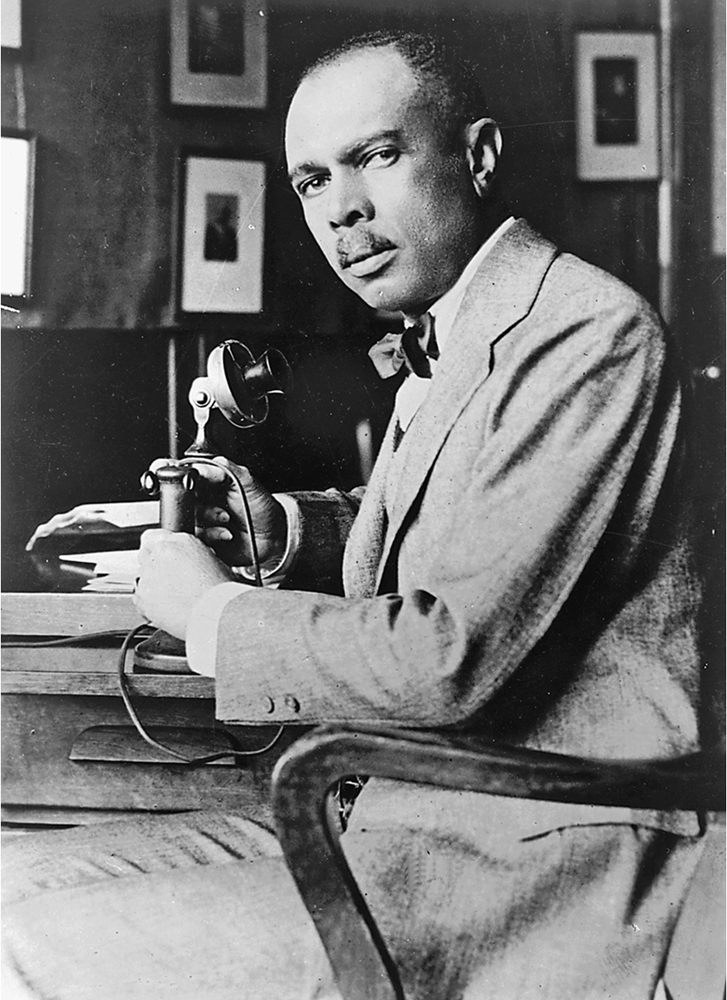

James Weldon Johnson

The success of the Harlem Renaissance was due, in part, to the older and established writers like James Weldon Johnson who helped and encouraged younger artists and writers. Johnson influenced many young black writers to come to Harlem to be part of the Renaissance movement. He provided them with contacts with his white editors working in white publications. Although Johnson was already in his fifties when the Harlem Renaissance began to bloom, he bloomed right along with it.

Next page