For Steve

Contents

Chapter 1:

Black and White Identity Politics

Chapter 2:

An Erotics of Race

Chapter 3:

Let My People Go: Lillian E. Wood Passes for Black

Chapter 4:

Josephine Cogdell Schuyler: The Fall of a Fair Confederate

Part Three:

REPUDIATING WHITENESS: POLITICS, PATRONAGE, AND PRIMITIVISM

Chapter 5:

Black Souls: Annie Nathan Meyer Writes Black

Chapter 6:

Charlotte Osgood Mason: Mother of the Primitives

Chapter 7:

Imitation of Life: Fannie Hursts Sensation in Harlem

Chapter 8:

Nancy Cunard: I Speak as If I Were a Negro Myself

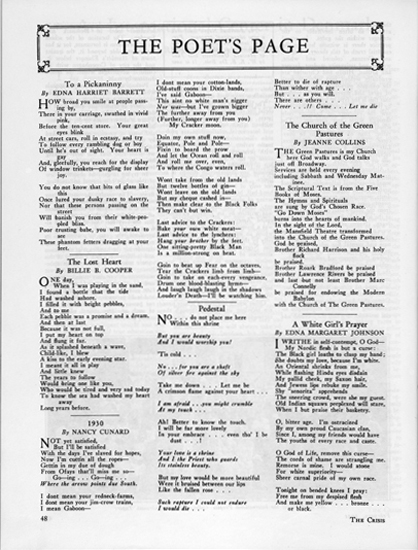

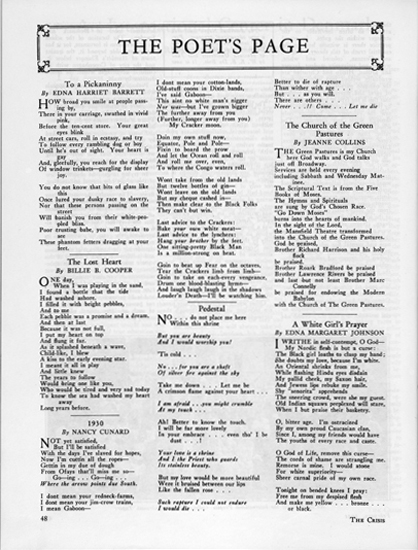

A White Girls Prayer in The Poets Page, The Crisis

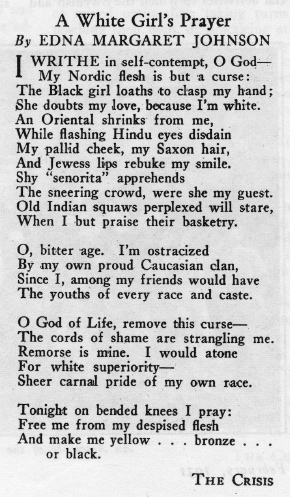

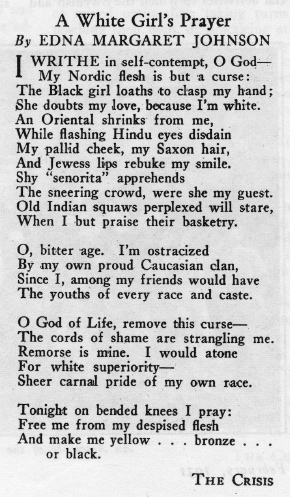

Fania Marinoff in Harlem

Harlem After Dark cartoon

Amy Spingarn

Opportunity awards invitation

Tourist map of Harlem

Harlem street scene

Newspaper composograph of Alice Jones Rhinelander at her 1925 trial

Etta Duryea

Etta Duryea and Jack Johnson

Miguel Covarrubias cartoon

Libby Holman and Gerald Cook

Harlem street scene

Blanche Knopf in drag

Libby Holman

NAACP benefit program, close-up

Mary White Ovington

Helen Lee Worthing and Dr. Nelson

Nancy Cunard, dancing

Lillian Wood and the Morristown College faculty

The Franklin sisters

Morristown College memorial bust

Morristown College for sale

The Schuyler family at home

The Cogdell family home in Granbury, Texas

Josephine Cogdell and the family cook

Josephine Cogdell as a pinup girl

John Garth, self-portrait

Josephine Cogdell as an artists model

Josephine Cogdell Schuyler

Josephine Cogdell Schuyler on a Harlem rooftop

Ernestine Rose

The Schuylers at home, reading

Josephine Cogdell Schuylers scrapbook

Josephine Cogdell Schuyler, photographed by Carl Van Vechten

Opportunity cover

Detail of program for Annie Nathan Meyers Black Souls

Annie Nathan Meyer

Program for Black Souls

Charlotte Osgood Mason

Charlotte Osgood Mason

Cudjo Lewis

Miguel Covarrubias cartoon

Nancy Cunard, holding Negro

Fannie Hurst at her desk

Fannie Hursts apartment

Fannie Hurst

Nancy Cunard, 1924

Nancy Cunard, with John Banting and Taylor Gordon, 1932 press conference

Nevill Holt

Nancy Cunard

Nancy Cunard, with a mask from Sierra Leone

Nancy Cunard, solarized by Barbara Ker-Seymer

Ruby Bates and the Scottsboro mothers

Toward the end of the 1920s, the NAACP journal, The Crisis, began to transform its Poets Page into a forum for white views of race, ranging from verses in the minstrel tradition to radical antiracist odes, often printed on the same page and without editorial comment. Although extreme, A White Girls Prayer spoke for many who longed for the exotic utopia they imagined Harlem could offer, just as Nancy Cunards 1930 voiced the belief of some white women that they could speak for, or as, blacks.

There were many white faces at the 1925 Opportunity awards dinner. So far they have been merely walk-ons in the story of the New Negro, but they became instrumental forces in the Harlem Renaissance.

Steven Watson, The Harlem Renaissance

You know it wont be easy to explain the white girls attitude, that is, so that her actions will seem credible.

Carl Van Vechten, Nigger Heaven

Fania Marinoff in Harlem.

I did not set out to write this book. Some years back, in the course of writing Zora Neale Hurston: A Life in Letters, I needed, but could not find, information on the many white women Hurston knew and befriended in Harlem: hostesses, editors, activists, philanthropists, patrons, writers, and others. There was ample material about her black Harlem Renaissance contemporaries: midwife Alain Locke; leading intellectual W. E. B. Du Bois; educator Mary McLeod Bethune; activists Walter White and Charles S. Johnson; actors Paul Robeson, Charles Gilpin, and Rose McClendon; and the array of Harlem Renaissance writers and artists from the cohort with whom she edited the radical journal Fire!!Wallace Thurman, Langston Hughes, Gwendolyn Bennett, Richard Bruce Nugent, Aaron Douglas, and John Davisas well as satirist George Schuyler, novelists Jessie Fauset and Nella Larsen, and poets Claude McKay and Counte Cullen, among others. The white men associated with the Harlem Renaissancewriter and honorary insider Carl Van Vechten; writers Sherwood Anderson and Waldo Frank; playwrights Eugene ONeill, Paul Green, and Marc Connelly; editor/satirist H. L. Mencken; activist Max Eastman; folklorists Roark Bradford and John Lomax; German artist Winold Reiss; anthropologists Franz Boas and Melville Herskovits; philanthropists Arthur and Joel Spingarn and Edwin Embreealso proved easy to research. But the white women were a problem. It seemed that there was virtually no information available about some of them. Many, such as Charlotte Osgood Mason, a wealthy patron known as the dragon lady of Harlem, were described with the same few sentences in every source on the Harlem Renaissance, sentences that I eventually learned were wrong (although not before I too had committed some of them to print).

We have documented every other imaginable form of female identity in the Jazz Agethe New Woman, the spinster, the flapper, the Gibson Girl, the bachelor girl, the bohemian, the twenties mannish lesbian, the suffragist, the invert, and so on. But until now, the full story of the white women of black Harlem, the women collectively referred to as Miss Anne, has never been told. White women who wrote impassioned pleas such as A White Girls Prayer (see frontispiece) about their longings to escape the curse of whiteness have rarely been regarded seriously.

Some believed they should not be. The press sexualized and sensationalized Miss Anne, often portraying her as either monstrous or insane. To blacks she was unpredictable, as likely to sentimentalize a gleeful, trusting, eye-rolling pickaninny, as Edna Barrett did on The Poets Page, or to claim that she could speak for black desires to murder Crackers, as Nancy Cunard did there also (see frontispiece), as she was to question or criticize her own status. And so, blacks did not necessarily welcome her presence either, although they often sidestepped saying so publicly or in print. Miss Anne crops up in Harlem Renaissance literature as a minor charactera befuddled dilettante or overbearing patron whose presence in cabarets or political meetings spawns outbreaks of racial violence. Occasionally, she is caricatured in black newspapers, as in this cartoon image of white women flocking to throw gold, jewels, and cars at one sexy young black man, known in those days as a sheik. Relying on these stock characters, we might believe that she was found only in cabarets, drinking and jig-chasing (pursuing black lovers), or enthroned on New Yorks Upper East Side, bankrolling black writers. Historians and critics such as Kevin Mumford, Susan Gubar, and Ann Douglas dismiss these women as slummers guilty of sinister... vampirism and pronounce their incursions into Harlem undeserving of serious inquiry. Even Baz Dreisingers recent

Next page