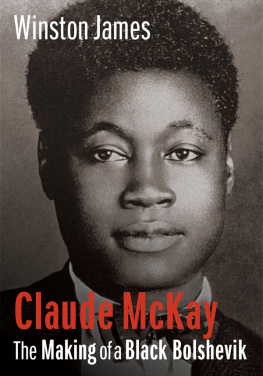

Claude McKay

Wayne F. Cooper

Claude McKay

Rebel Sojourner in the Harlem Renaissance

A Biography

Louisiana State University Press

Baton Rouge and London

To Jean

Copyright 1987 by Louisiana State University Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Designer: Laura Roubique

Typeface: Primer

Typesetter: G & S Typesetters, Inc.

Printer and binder: Thomson-Shore, Inc.

Louisiana Paperback Edition, 1996

05 04 03 02 01 00 99 98 97 96 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cooper, Wayne F.

Claude McKay: rebel sojourner in the Harlem Renaissance.

Revision of thesis (Ph.D.)Rutgers University, New Brunswick.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. McKay, Claude, 18901948Biography. 2. Authors, American20th CenturyBiography. 3. Authors, Jamaican 20th CenturyBiography. 4. Harlem Renaissance.

5. Afro-American arts. 6. Afro-AmericansIntellectual life. I. Title.

PS3525.A24785Z63 1987 818.5209[B] 8618505

ISBN 0-8071-1310-7 (cloth) ISBN 0-8071-2074-X (pbk.)

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Contents

Illustrations

Preface and Acknowledgments

I n this biography of Claude McKay I have attempted two things. One is to make clear McKays importance as a pioneer in twentieth-century black literature in the West Indies, the United States, and Africa. The second is to portray as accurately as possible the man and the artist from his birth in 1890 to his death in 1948. The first objective was more easily accomplished than the second.

There can be no doubt of McKays importance as a pioneering black writer. In 1912 he produced two volumes of Jamaican dialect poetry that have long been recognized as unique and important contributions to a distinctive West Indian literature. Throughout McKays career, Jamaica occupied a central, unifying place in his poetry and fiction, and he is today generally recognized as one of the earliest and most important black voices in the new West Indian literature that has developed in this century, largely since World War II.

His place as a forerunner to recent West Indian literature remains secure despite the fact that McKay left Jamaica in 1912 at the age of twenty-two and never returned. Like several other articulate West Indians in this century, he achieved his best work and won his largest audiences in the United States and Europe. During a lifetime of travel and observation, he produced penetrating commentaries on modern colonialism in which he clearly anticipated such later West Indian expatriates as George Pad more, C. L. R. James, Frantz Fanon, Derek Walcott, and V. S. Naipaul.

McKay also played an important role in the development of modern black American literature in the United States. In New York City, his militant protest poetry after World War I inaugurated a decade of intense black literary activity known as the Harlem Renaissance or the New Negro movement. His forthright declarations of alienation, anger, and rebellion after World War I gave early expression to themes that have since figured prominently in black American writing. And in his novels published in the late 1920s and early 1930s, he joined the other black writers of the 1920s who had begun to explore the continued relevance of their folk roots in Africa, the West Indies, and the rural Southa preoccupation that has by no means disappeared from recent black American literature.

McKays novels, particularly his second, Banjo, published in 1929, also exerted a profound catalytic influence upon certain young French West Indians and West Africans, notably Lopold Sdar Senghor from Senegal and Aim Csaire from Martinique. These two men would later acknowledge McKays strong influence in their development of the literary doctrine of Ngritude, which dominated black French writing in the years after World War II.

Finally, it must be said that McKays political and social commentary, embodied in his numerous articles over three decades (19181948) and in such books as A Long Way from Home (1937), Harlem: Negro Metropolis (1940), and The Negroes in America (1923), contained often prophetic statements on issues that later became increasingly important to black Americans and to the nation in general. In his articles and essays, McKay dealt at length with crucial black issues: the debate over traditional, civil rights-oriented integration versus strong, black, community-based ethnic development; and the importance of ethnic pluralism in American and world development. In addition, he commented intelligently on a range of historical problems associated with European imperialism, Western democracy, anticolonialism, and the rise of Russian communism.

In his essays, McKay came closest to developing a consistent stylistic excellence; in poetry and fiction he was never a stylistic innovator. But in all his works, he seized intuitively upon those themes of identity, alienation, rebellion, and community development that have dominated black literatureand much of Western literature in generalin this century.

In this study I have concentrated a good deal of attention on McKays literary works, because most of his adult life was concerned with their production, and they remain in fact the chief reason for his enduring importance. Nevertheless, this is primarily a biography, not a work of literary analysis; its central focus is McKays life, not simply his literature.

As an individual and as a literary artist, McKay was to an extraordinary degree deeply involved in the action and passion of his times. As a young Jamaican colonial, as an immigrant poet and political radical in the United States after World War I, as a doubly expatriated writer in Europe and North Africa from 1922 until 1934, as a politically conscious member of the Federal Writers Project in New York City in the 1930s, and finally as a disillusioned secular idealist and world-weary convert to Catholicism in the 1940s, he participated in and wrote about some of the major historical events of this century. At the same time, he maintained a curious detachment and stubborn independence that ultimately left him isolated and lonely.

In many ways, his was a paradoxical personality, characterized always by a deep-seated ambivalence. Yet, despite years of wandering and personal isolation in many lands, he remained always securely anchored to a positive identity as the proud son of Jamaicas independent black peasantry. This self-confidence in his essential identity existed side by side with his ambivalence and his need for support and reassurance from a succession of patrons. And coloring both was an ever-present ironic awareness that his humanity could never be defined entirely by the simple boundaries of color and race.

Personally he was a complex and often exasperating man, alternately charming and spiteful, noble and petty, wise and self-deceptive. Through all his moods, he tried to the very end of his life to maintain in his political and social criticism a dispassionate objectivity and intellectual honesty that would transcend whatever weaknesses he had as a man. This very attitude, however, often led to profound misunderstandings and bitter conflicts.

On the whole, of course, it must be remembered that writers and artists, especially in the rootless turmoil of recent times, have often had difficult personalities and lonely lives. Judged in relation to such contemporaries as Robert Frost, Ezra Pound, and Ernest Hemingway (to name only three), McKays personality was complex but stable, even engaging in its flexibility.

Next page