Measuring the Harlem Renaissance

Measuring the Harlem Renaissance

The U.S. Census, African American Identity, and Literary Form

Michael Soto

University of Massachusetts Press

Amherst and Boston

Copyright 2016 by University of Massachusetts Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-1-61376-486-2

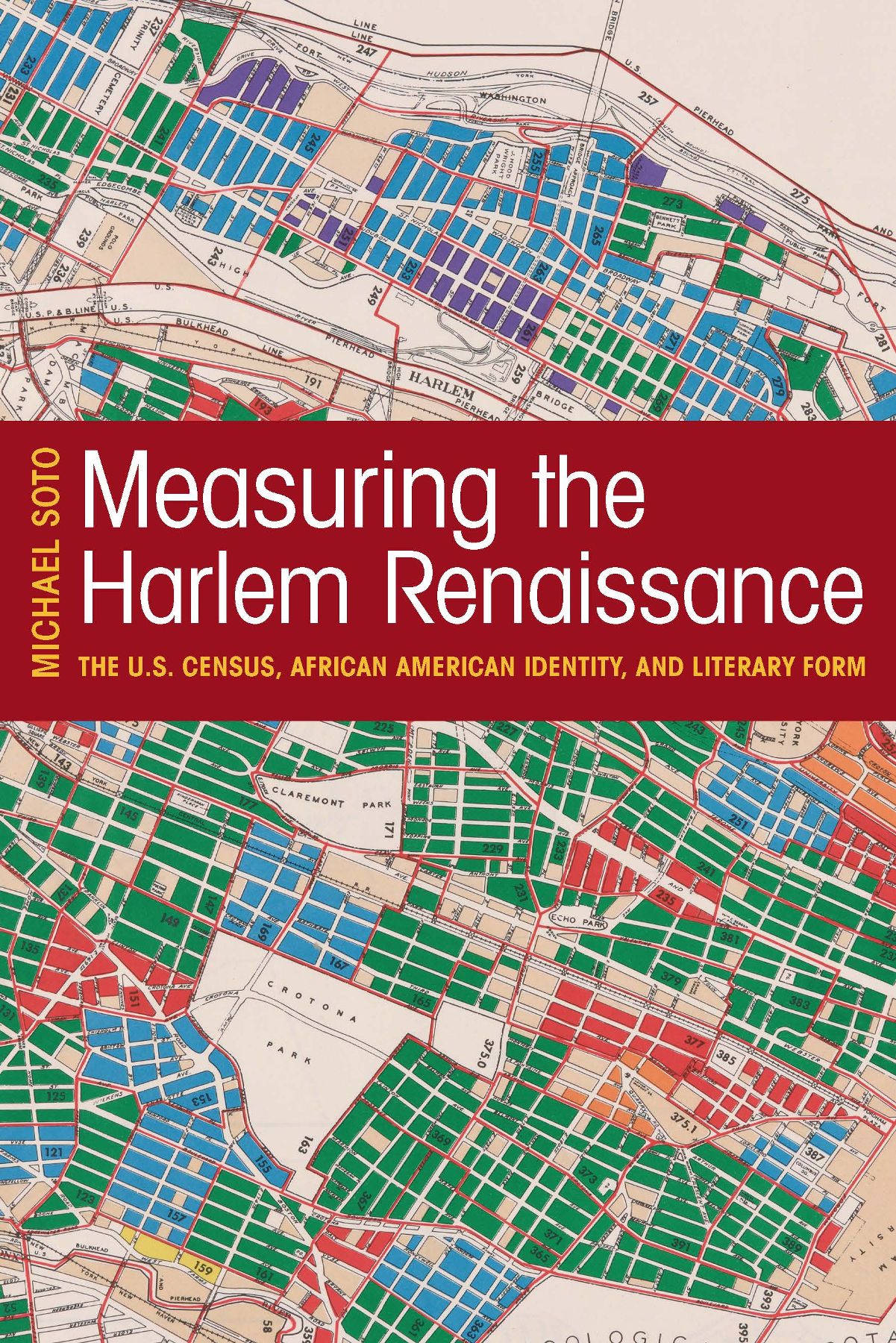

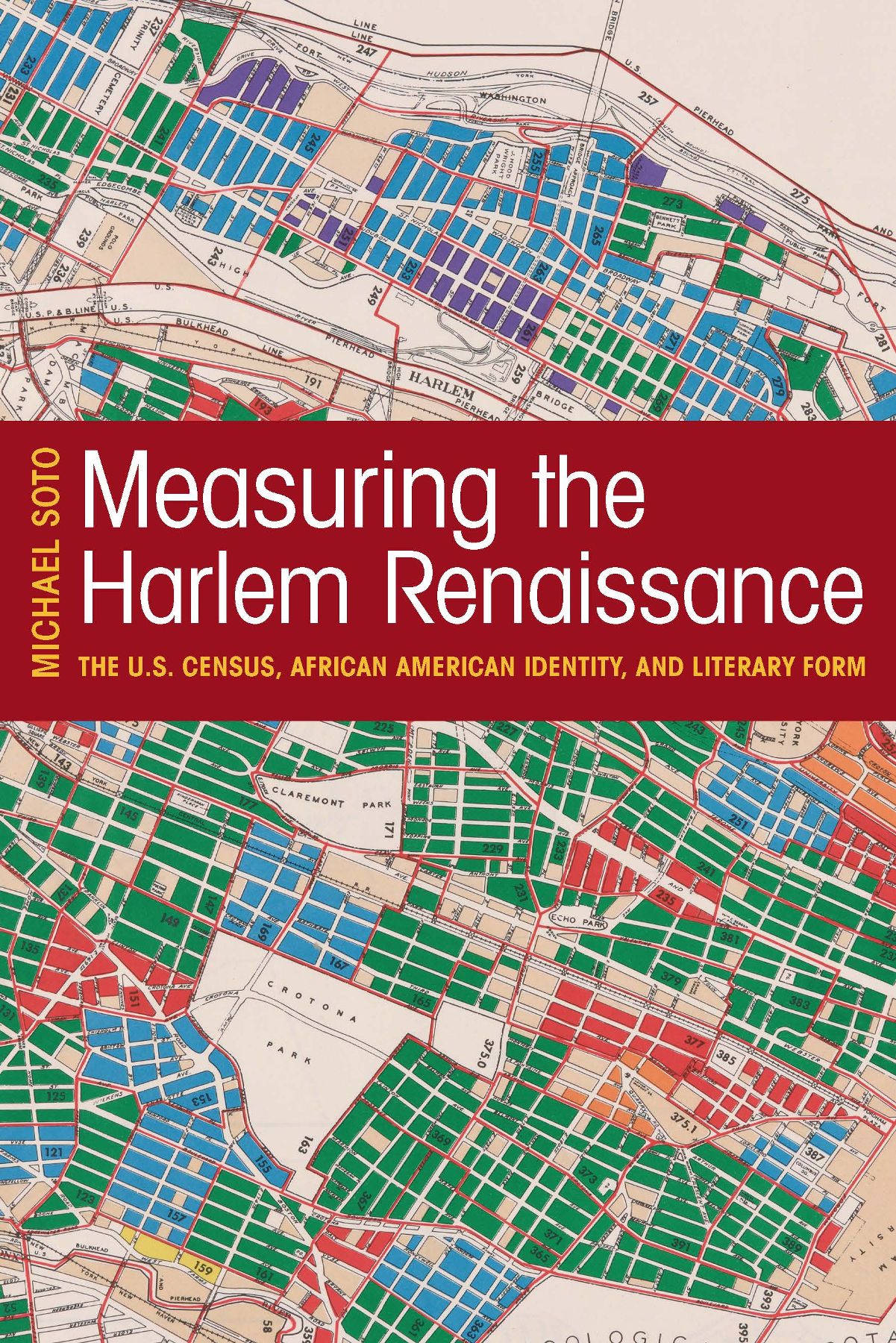

Cover design by Sally Nichols

Cover art: Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. Population distribution map. The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1945. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/b9f2b588-8fb6-d39b-e040-e00a180679bc

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Soto, Michael, 1970 author.

Title: Measuring the Harlem Renaissance : the U.S. Census, African American

identity, and literary form / Michael Soto.

Description: Amherst : University of Massachusetts Press, [2016] | Includes

bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016031027| ISBN 9781625342508 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN

9781625342492 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: American literatureAfrican American authorsHistory and

criticism. | American literature20th centuryHistory and criticism. |

Harlem Renaissance. | United StatesCensusHistory. | Harlem (New York,

N.Y.)Intellectual life20th century. | Modernism (Literature)United

States. | African Americans in literature.

Classification: LCC PS153.N5 S6465 2016 | DDC 810.9/896073dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016031027

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

for Amrico Benjamn

Contents

As I write this I can look out of my office window to see the downtown San Antonio skyline, a view dominated by high-rise bank buildings, River Walk hotels, the Tower of the Americas, and the Alamodome sports venue. The seventy-five-story Tower was completed in 1968, just in time for the HemisFair worlds fair, an event that endowed the city, finally, with a twentieth-century outlook. Twenty-five years later, the Alamodome was constructed to host large-scale concerts and sporting events and to house an as-yet-unrealized National Football League franchise. Between them, on the eastern edge of downtown, runs U.S. Interstate 37, carved out of the San Antonio geography during this same period in a process that displaced hundreds of families and that cemented, quite literally, the historical divide between downtown and the predominantly African American East Side area. Just northeast of downtown I can also see Fort Sam Houston, a large military outpost that for decades has done much to heal the citys racial fractures.

Beginning a book about the so-called long Harlem Renaissance with brief and incomplete reflections about the racialized geography of a South Texas city strikes no one, I hope, as too far misplaced. After all, Harlem holds a grip on the American cultural imagination as the paradigmatic African American urban enclave; its story shapes my view of San Antonio society in untold ways. Nor does it shape my view alone. In 2014, when the U.S. Department of Education awarded the local United Way with a Promise Neighborhood grant to support renewal in the East Side, numerous references to Harlem, and specifically to the Harlem Childrens Zone, which inspired the national program, seasoned homegrown reporting and political discourse. Similar rhetorical gestures by now look familiar: as Harlem went a century ago, so went the rest of black America in the following decadesnever mind that the facts of life in San Antonio bear little resemblance to those of New York City.

For at least a century, Harlem has been known by many metaphors, many symbolic restatementstest tube, Mecca, city of refuge, Negro metropolis, cultural capital of black America, a raisin in the sunthat recommend part (Harlem) for whole (black America) social and cultural analysis. Even when Langston Hughes, who gave us the raisin metaphor, lampooned the notion that creative literature might play a role in the day-to-day lives of Harlemitesordinary Negroes hadnt heard of the Negro Renaissance, he quipped in The Big Sea, And if they had, it hadnt raised their wages anyhe nonetheless looked forward to a day when his humorous dismissal might no longer apply, when serious literature might take on equally serious cultural work.

It is to Hughes and to his fellow creative writers that I look for guidance when taking up sociohistorical questions about Harlem and the wider American landscape. Measuring the Harlem Renaissance interrogates the basic assumption of most Harlem Renaissance scholarship and much of its literature: that a clear connection exists between social life and cultural production; that historical experience gives birth to literary and artistic expression. Part of the allure of Harlem Renaissance literature, for scholars and for more casual readers, is its constant engagement with questions of sociohistorical importance. Yet the social facts behind these questions are routinely taken for granted, with no recourse to empirical evidence that has been collected for decidedly nonliterary purposes.

Much closer at hand, stacked high on my desk, are the numerous Census Bureau volumes, photocopies of New York City and New York State government reports, and printouts of the computer spreadsheets that Ive assembled to better understand Harlem social life during the early part of the twentieth century. The novels, poems, short stories, and plays of the Harlem Renaissance line the bookshelves along my office walls; these are joined by decades of scholarship on the subject, beginning with Franck L. Schoells La renaissance ngre aux tats-Unis (1929), a Revue de Paris overview of the ongoing movement, and Melvin B. Tolsons The Harlem Group of Negro Writers (1940), his retrospective Columbia University masters thesis. Such early ventures are joined by Nathan Irvin Hugginss seminal Harlem Renaissance (1971), David Levering Lewiss feisty When Harlem Was in Vogue (1981), and too many of their scholarly heirs to count here.

As I look back and forth between my bookshelves and my desk and the view outside, Im tempted to yoke the images together with a sweeping rhetorical gesture. But Ill resist. What strikes me most about the birds-eye view of my adopted home city is the wide discrepancy between the facts on the ground and the hazy, romanticized versions of San Antonio handed down by such writers as Sidney Lanier or even Jack Kerouac. No such problem emerges from a consideration of Harlem, progenitor of what James de Jongh aptly describes as a vicious modernism. And yet the book that follows is no mere catalog of a doctrinaire realism that arose in response to urban squalor, nor does it imply (I hope) a narrow range of literary responses to social reality. Anyone familiar with more than a handful of Harlem Renaissance texts knows that they veer from social realism to avant-garde surrealism, from detached imagism to syrupy love sonnets. Heres why: there is no such thing as Hughess ordinary Negro. The social landscape of Harlem was so complex, so intriguing during the heyday of the renaissance that bears its name that no one approach, to literary representation or to social analysis, could ever hope to offer but a partial and provisional view of the facts on the ground.

Let me conclude here by thanking a number of kind people and institutions for their role in supporting this book along its winding path. Drafts of selected portions of

Next page