Published in 2013 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright 2013 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2013 Rosen Educational Services, LLC.

All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Senior Manager

Adam Agustyn: Assistant Manager

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

Kathleen Kuiper: Senior Editor, Arts and Culture

Rosen Educational Services

Jeanne Nagle: Senior Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Brian Garvey: Designer, Cover Design

Introduction by Laura Loria

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Painters of the Renaissance/edited by Kathleen Kuiper.

pages cm(The Renaissance)

In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61530-883-5 (eBook)

1. Painting, Renaissance. 2. PaintersEuropeBiography. I. Kuiper, Kathleen, editor.

ND170.P35 2012

759.03dc23

2012029042

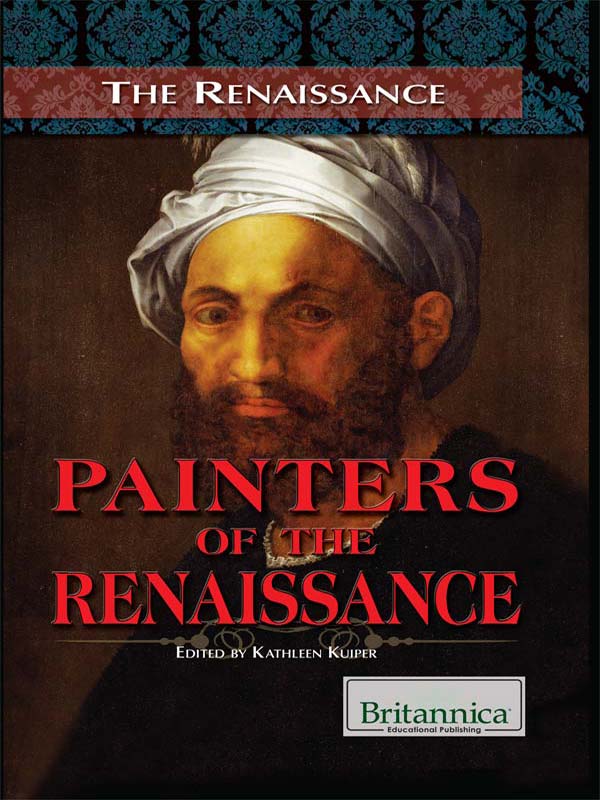

On the cover, p. iii: Portrait of Michelangelo. Imagno/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Cover (background pattern), pp. i, iii, 1, 20, 50, 105, 140, 160, 210, 211, 213, 216

iStockphoto.com/fotozambra; p. x (sun) Hemera/Thinkstock; remaining interior graphic elements iStockphoto.com/Petr Babkin

T he European Renaissance was more than an era of new ideals. It was the end of a struggle to survive in the Middle Ages. Plague, war, and famine had weakened the region for centuries. By the late 14th century, Europe had recovered sufficiently to be in a position to move forward, artistically and otherwise. Changing political, religious, and social thought was reflected in the artwork of the 15th and 16th centuries. While borrowing heavily from ancient Western civilizations, Renaissance art also was unique in its realism, use of technique, and enduring beauty. The major artists of the time are considered masters because their work was and continues to be admired, revered, studied, and copied to this day. Painters of the Renaissance explores progress in the art world at this time, as well as the artists who moved the craft forward.

For all intents and purposes, the period of artistic rebirth that scholars have named the Renaissance began in Italy, spreading across the continent over time. Paintings had a decidedly humanistic bent. Portraits of common (versus noble) individuals and the towns and villages in which they resided became the focus of the art world. Artists themselves were no longer considered mere craftsmen, but intellectual, creative technicians who were known by name.

The defining boundaries of Renaissance art vary from region to region, but the era is sometimes divided into three periods: early (1420-95); High, or classic (1495-1520) and Late, or Mannerist (1520-1600). Artists of the Early Renaissance, centred chiefly in Florence, Italy, were unified by their humanist approach, although they employed a variety of styles. Even paintings with religious subject matter were grounded in earthly terms; they highlighted the humanity of figures within a sacred scene rather than presenting static or remote objects of worship. The paintings of Fra (Brother) Angelico, the Dominican friar who is credited with initiating the genre of painting known as sacra conversazioneMary and the Christ Child with saints (and sometimes donors) surrounding, depicted in a single panel of an altarpiece as if in conversationserve as an example of the humanist touch pervading early Renaissance devotional works.

Thanks largely to the writings of Italian architect Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446), the use of perspective, wherein an artist incorporates linear convergence to provide the illusion of depth and distance, as well as spatial relationships between objects in a painting, was on the rise at this time. By manipulating light and shadow, and employing geometric lines and set proportions, the artist could draw the viewers eye in a specific direction, and create something of a three-dimensional effect. Paolo Uccello was an especially adroit practitioner of perspective, but some of his most famous pieces, including Battle of San Romano, also incorporate multiple perspectives, rather than the single, linear perspective popular with other artists of the time.

Masaccio, who is considered the father of Renaissance painting, pioneered the use of one-point perspective to make works such as The Trinity appear three-dimensional, and thus extremely realistic. Masaccios career was briefcovering a span of time from his entrance in a painters guild at 21 until his death six years laterbut his works are, in many ways, the epitome of early Renaissance art, with their emphasis on simplicity and humanism. His impact was felt during his lifetime and on through the mid-15th century. Madonna and Child by Fra Filippo Lippi, a contemporary of Masaccio, shows the influence of the latter artist in the sculptural quality of its figures. Piero della Francesca, a younger painter, incorporates the styles of Masaccio and Fra Angelico in his works, with the added touch of a unique light colour palette all his own. Later in the 15th century, artists began to incorporate more movement in their works through depictions of detailed musculature and flowing fabric.

Self-portrait by Sofonisba Anguissola, shown at work. The Bridgeman Art Library/Getty Images

These new artistic ideals spread throughout Italy during the early Renaissance period; other cities began to rival Florence in artistic achievement. Andrea Mantegna borrowed spatial concepts from the Florentines, but put his unique stamp on his frescoes by lowering the perspective lines, an innovation that gave his figures a certain monumentality and increased the illusion of height. Mantegnas early years in Padua, a university town that hosted scholars from across Europe, heightened his interest in all things classical, which was reflected in his art. His brother-in-law, Giovanni Bellini, combined the influence of Mantagna with that of others, including his father, Jacopo, letting his media dictate the approach to each piece. His change from tempera to oil paint, which gave him a greater ability to experiment with shading, allowed him to refine his depiction of the fall of natural light and to create a particular mood.