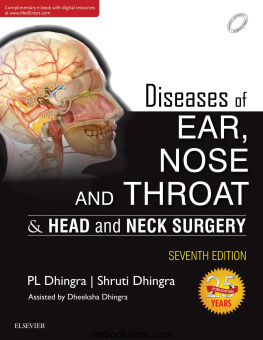

EAR, NOSE, AND

THROAT

THE HUMAN BODY

EAR, NOSE, AND

THROAT

EDITED BY KARA ROGERS, SENIOR EDITOR, BIOMEDICAL SCIENCES

Published in 2012 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.)

in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright 2012 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica,

and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All

rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2012 Rosen Educational Services, LLC. All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor

J.E. Luebering: Senior Manager

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

Kara Rogers: Senior Editor, Biomedical Sciences

Rosen Educational Services

Alexandra Hanson-Harding: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Matthew Cauli: Designer, Cover Design

Introduction by Monique Vescia

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ear, nose, and throat / edited by Kara Rogers.1st ed.

p. cm.(The human body)

In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61530-709-8 (eBook)

1. OtolaryngologyPopular works. I. Rogers, Kara.

RF59.E17 2012

617.51dc23

2011013432

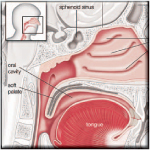

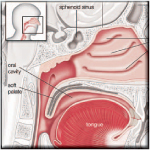

On the cover: A side view of the ear, nose, and throat. SuperStock, Inc.

On page : Dr. Maura Shea examines a patients ear through an otoscope at the Codman Square Health Center April 11, 2006, in Dorchester, Massachusetts. Joe Raedle/Getty Images

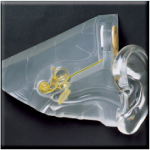

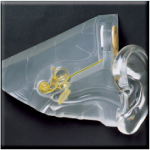

On pages : The human inner ear. Shutterstock.com

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

W hen an airplane begins its initial descent, passengers often chew gum or yawn to clear their ears because they feel bothered by changes in air pressure. The common cold is notorious for obscuring our ability to taste food. Common experiences such as these demonstrate the close physiological relationships shared by the ear, nose, and throat. These tissues, however, also perform separate functions within the human body. As youll discover in this book, the ear, nose, and throat play key roles in the respiratory and alimentary systems and are essential to the bodys health. At the same time, each of these tissues performs a unique function. For example, the structures of the throat enable vocal expression, the ear enables hearing and balance, and the nose is central to the senses of taste and smell. Until the late 19th century, however, physicians considered each organ separately. For example, otologists specialized exclusively in the ear, and laryngologists diagnosed and treated disorders of the throat and larynx. Once the interdependence of the ear, the nose, and the throat came to be better understood, the medical sciences of otology and laryngology were unified in a specialized fieldotolaryngologydevoted to the study and treatment of diseases and disorders associated with all three organs. Today, otolaryngology is often referred to simply as ENT (short for ear, nose, and throat).

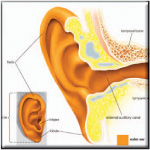

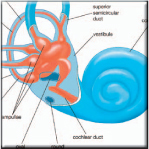

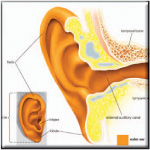

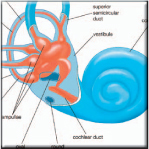

When scientists began studying the design of the human ear, they often used architectural terms to describe its features. Hence, the human ear is said to have walls and windows, a vestibule, and a ceiling. In William Shakespeares play Hamlet, one character kills another by pouring poison into the porches of his ears. The inner ear even includes two labyrinths, one inside the other. This highly developed organ is responsible for two entirely different functions: the sense of hearing and the sense of equilibrium. The latter is governed by the vestibular system and enables an individual to maintain his or her balance. For hearing, the ear transforms the vibrations of sound waves into nerve impulses, which the brain then interprets as sound. Scientists do not fully understand the extremely complex process by which vibrations in mediums such as air and water are ultimately recognized by the brain as sound. They do know, however, that in the ear the energy of sound experiences a unique transformation from wave vibration to nerve impulse. This impulse is responsible for relaying information about sound waves to the sound-processing centre of the brain.

The process of hearing begins in the outer ear, where vibrations in the air are channeled toward the tympanic membrane, or eardrum, in the middle ear. There, the vibrations are transferred to the eardrum and to minute ear bones known as ossicles. These movements create vibrations in the fluid of the cochlea, a structure in the inner ear that contains the sensory organ of hearing and that is distinguished by its coiled shape, which resembles a snails shell. The vibrations in the cochlear fluid create waves that travel along the basilar membrane (one of three membranes in the cochlea). These waves then stimulate hair cells in a structure known as the organ of Corti. The hair cells convert the waves to nerve impulses, which are then transmitted to the brainstem for processing.

The ear bones found in the middle ear are present in the ears of all mammals. These bones consist of the malleus, the incus, and the stapes, which are commonly referred to as the hammer, the anvil, and the stirrup, respectively. The ear contains the smallest bones in the human body, and hearing would be impossible without them.

Next page