THE EYE: THE PHYSIOLOGY OF HUMAN PERCEPTION

THE HUMAN BODY

THE

EYE

THE PHYSIOLOGY OF HUMAN PERCEPTION

EDITED BY KARA ROGERS, SENIOR EDITOR, BIOMEDICAL SCIENCES

Published in 2011 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.)

in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright 2011 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2011 Rosen Educational Services, LLC.

All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor

J.E. Luebering: Senior Manager

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

Kara Rogers: Senior Editor, Biomedical Sciences

Rosen Educational Services

Alexandra Hanson-Harding: Senior Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Matthew Cauli: Designer, Cover Design

Introduction by Sean Price

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The eye: the physiology of human perception / edited by Kara Rogers. 1st ed.

p. cm. (The human body)

In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61530-255-0 (eBook)

1. EyePopular works. 2. PerceptionPhysiological aspectsPopular works. I. Rogers, Kara.

QP475.5.E94 2010

612.84dc22

2009051116

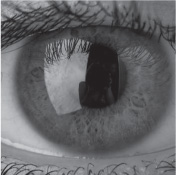

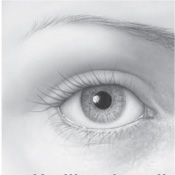

On the cover: The adult human eye is only 24 mm (1 inch) high and slightly wider. This organ receives an astonishing amount of information and conveys it to the brain for processing. http://www.istockphoto.com / Mads Abildgaard (head), Nurbek Sagynbaev (eye)

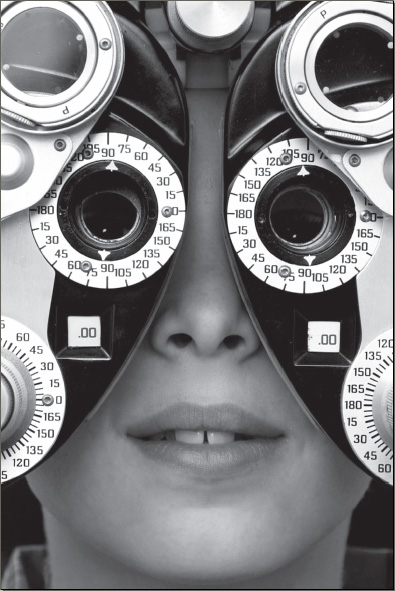

Introduction: Patient being fitted for glasses by an eye specialist. Shutterstock.com

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

The scientific study of the eye is believed to have originated with the Greek physician Herophilus, who lived from about 335 to 280 BCE. Indeed, from his work came the words that we use today to describe the various parts of the eye, including the words retina and cornea. In Herophilus day, scientists believed that we could see because beams of light came out of our eyes and fixed on objects. In the centuries since, doctors and anatomists have discovered that vision relies on just the opposite effect. Human eyes are actually light collectors. Light rays travel from objects around us and stimulate the light-sensitive cells in our eyes. This book takes a look at these amazing organs and how they function to allow us to see the world.

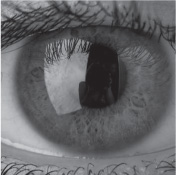

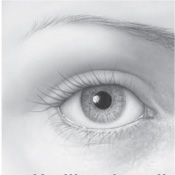

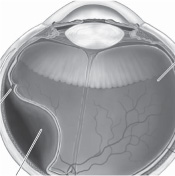

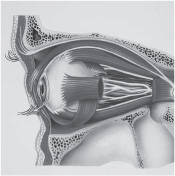

Anyone staring into another persons eye would notice that its exterior is mostly white. This part of the human eye, the sclera, is made up of fibrous tissue and provides a tough protective coating around the whole eyeball. The most noticeable part of any eye is the coloured iris and the dark pupil that it surrounds. The iris, which works much like the aperture of a camera, expands in darkness to let more light into the pupil and contracts in bright light to keep the light-sensitive cells from being overwhelmed. The colour of the iris comes from melanin, a substance that protects the eye from absorbing strong light. In the centre of the iris is the pupil, which allows light and other visual information into the interior of the eye. The iris and pupil are protected by a transparent, domelike cover called the cornea.

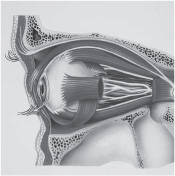

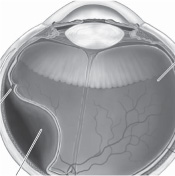

Light enters the interior of the eye by passing through a crystalline lens, which bulges or flattens, depending on how far away an image is, and then through a semisolid gel-filled chamber called the vitreous body. The vitreous body gives the eye shape and flexibility. Finally, the light reaches the retina, a membrane made up of layers of cells, which receive visual information and transmit this information to the brain.

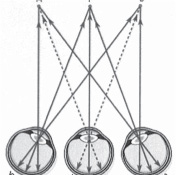

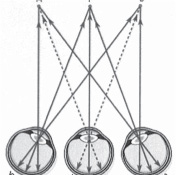

The eyes would not be able to receive this information if they did not move. How they move is a complicated process. Eyeballs are set into protected parts of the skull called eye sockets. Between the sockets and the eyeballs are layers of fat and six thin muscles that gently tug the eyeball in one direction or another. Most of the actual movements of the eyes are carried out without awareness. For example, when a person sees bright light at the edge of the field of vision, he or she is immediately drawn to look at it. This response is called the fixation reflex. Scientists have also learned that the eyes move a number of times within a single second. These tiny movements help keep the eyes focused on a world that is constantly in motion and stimulate the retina to take in fresh visual information even with stationary objects.

Eyes are delicate and precise organs that are vulnerable to problems. There are, however, a number of mechanisms in place to protect the eyes. Eyebrows and eyelashes keep out dust, sweat, and other irritants. Eyelids lubricate the surface of the eyeball and protect against the introduction of foreign bodies into the eye. Lacrimal glands at the outside upper corner of each eye create a steady supply of tears to keep the eyeballs moist. Tearsproduced by irritation, yawning, and cryingalso contain bacteria-killing enzymes that destroy infections. To keep the eyes moist, we blink, often involuntarily.

Next page