MODERN PHILOSOPHY

FROM 1500 CE TO THE PRESENT

The History of Philosophy

MODERN PHILOSOPHY

FROM 1500 CE TO THE PRESENT

EDITED BY BRIAN DUIGNAN, SENIOR EDITOR,

PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION

Published in 2011 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.)

in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright 2011 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2011 Rosen Educational Services, LLC.

All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor

J.E. Luebering: Senior Manager

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

Brian Duignan: Senior Editor, Philosophy and Religion

Rosen Educational Services

Heather M. Moore Niver: Rosen Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Matthew Cauli: Designer, Cover Design

Introduction by Brian Duignan

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Modern philosophy : from 1500 CE to the present / edited by Brian Duignan.1st ed.

p. cm. -- (The history of philosophy)

In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61530-245-1 (eBook)

1. Philosophy, Modern. I. Duignan, Brian.

B791.M655 2011

190dc22

2010011553

On the cover: Preeminent Western philosophers such as Friedrich Nietzsche enriched modern philosophy, making it more pertinent than ever. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

On page : Sir Isaac Newton was the paramount figure of the scientific revolution of the 17th century. Photos.com

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

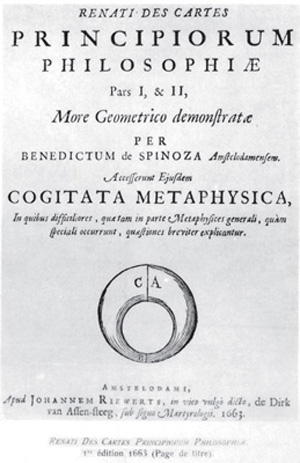

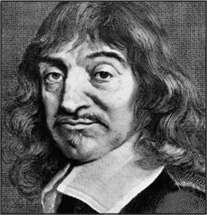

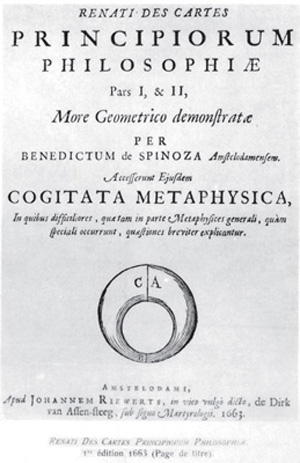

In 1664 Ren Descartes published Principles of Philosophy, a compilation of his physics and metaphysics. Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

D uring the 14th century, European society suffered an unprecedented series of natural and human-made disasters, including famine, the Black Death, and numerous devastating and expensive wars. By the end of the century, the continent was a great deal poorer and much less populous than it had been in 1300. According to some historians, these calamities were the death knell of the Middle Ages: the drastic changes they brought about hastened the disappearance of characteristically medieval forms of political authority and social organization. More important, they also served to undermine confidence among late-medieval thinkers in dogmatic Christian and Aristotelian doctrines concerning the principles of the natural world, the proper structure and governance of human society, and the capacities and moral worth of human beings.

Other scholars see the 14th century as merely a temporary interruption in processes of social and intellectual transformation that had begun several centuries earlier and would have continued as they did whether or not the disasters of the period had ever occurred. However this may be, it is clear that by the late-15th century European society and intellectual culture had changed in significant ways. The national monarchies had completely eclipsed the power of the German Holy Roman Empire, whose leader had been crowned by the pope since the early Middle Ages as the supreme secular authority on earth. In Italy, independent city-states such as Florence, Venice, and Milan were economically and militarily powerful, and elsewhere the growth of commerce and manufacturing further increased the importance of cities and the merchant classes at the expense of the landed nobility.

This period was also marked by the rise of humanism, an intellectual movement that emphasized the dignity of the human individual. The humanists were responsible for the rediscovery and translation of a wealth of ancient Greek and Roman literary and philosophical texts, including the complete dialogues of Plato. They revered the ancients, as they called the Greeks and Romans, for their intellectual rigour and integrity and for the freedom with which they pursued philosophical and scientific problems. In the latter respect ancient philosophers, in the estimation of the humanists, were far superior to the academic philosophers of previous centuries, the Schoolmen or Scholastics, who had been bound in their investigations to support, or at least not to contradict, the theology of the Roman Catholic Church. Indeed, the humanists regarded the Middle Ages (a term they invented) as a long period during which significant philosophical and literary activity had simply ceased. They understood themselves as the inheritors and standardbearers of Classical ideals against stultifying medieval orthodoxies. The term Renaissance was the somewhat judgmental invention of humanist sympathizers of the 19th century; nevertheless, it aptly conveys the intellectual renewal and reawakening that the humanists brought about.

Thus the humanists self-consciously took up where the ancients had left off. In philosophy, this is apparent not only in the new influence of ancient philosophical doctrines such as atomism and Stoicism but also in the revival of whole areas of philosophy that had been well developed in ancient times but relatively neglected during the Middle Agesparticularly political philosophy, epistemology (the study of knowledge), and ethics.

Modern Western philosophy conventionally begins in about 1500 and continues to the present day. This span of more than 500 years comprises four or five smaller periods: the Renaissance (15001600), the early modern period (16001700), the modern period (17001900)sometimes subdivided into the Enlightenment (17001800) and the 19th centuryand the contemporary period (1900present).

Next page