Nature, Human Nature, & Human Difference

Nature, Human Nature, & Human Difference

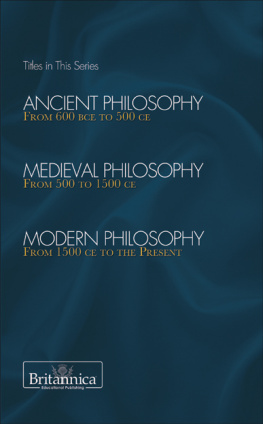

Race in Early Modern Philosophy

Justin E. H. Smith

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2015 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smith, Justin E. H.

Nature, human nature, and human difference : race in early modern philosophy / Justin E. H. Smith.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-15364-3 (hardback : acid-free paper)

1. RacePhilosophy. 2. EthnicityPhilosophy. 3. Philosophy of nature. 4. SciencePhilosophy. 5. Evolution (Biology) I. Title.

GN269.S65 2015

305.8001dc23

2014048310

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Sabon LT Std

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Again, we may decry the color prejudice of the South, yet it remains a heavy fact. Such curious kinks of the human mind exist and must be reckoned with soberly.

W.E.B. DuBois, The Souls of Black Folk (1903)

I am black. At the same time, I have always held the religion of science to be the only true one, the only one worthy of the constant attention and the infinite devotion of any man who allows himself to be guided by nothing but free reason. How could I reconcile the conclusions that seem to be drawn from this same science against the aptitudes of the Blacks with this passionate and deep veneration that is for me a profound need of the intellect?

Antnor Firmin, On the Equality of the Races (1885)

Whatever is killed and can be killed, necessarily lives.

Anton Wilhelm Amo, On the Impassivity of the Human Mind (1734)

Contents

Acknowledgments

This book was written with the support of a research grant for the period 200912 from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. It came together in its present form during a research sabbatical as a member at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, in the winter and spring of 2011. Parts of previously appeared in History of Science 50, 4 (December 2012). Material that later found its way into the book has been presented in more forums than I can document, including the Committee for Interdisciplinary Science Studies at the CUNY Graduate Center; the University of South Florida; the Humboldt University of Berlin; Universit Paris DiderotParis 7; the cole Normale Suprieure, Paris; the University of Helsinki; the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton; Villanova University; and the Montreal Interuniversity Workshop in the History of Philosophy. The present version of the book has benefitted from inspiring discussions with, and from the careful readings and helpful comments of, Delphine Antoine-Mahut, Matthew Barker, Magali Bessone, D. Graham Burnett, Nathaniel Adam Tobias Coleman, Harvey Cormier, James Delbourgo, Claude-Olivier Doron, Franois Duchesneau, Beth Epstein, Victor Emma-Adamah, Dan Garber, Bryce Huebner, Julie Klein, Antoine Leveque, David Livingstone Smith, Koffi Maglo, Stephen Menn, Adriaan Neele, Anne-Lise Rey, Jason Stanley, Tzuchien Tho, Catherine Wilson, Charles T. Wolfe, and two anonymous and extremely insightful referees for Princeton University Press. Particular gratitude and admiration are reserved for Adina Ruiu, from whom I learn so much. The employees of La Prsence Africaine bookstore in the rue des coles have generously helped me over the past year to discover many remarkable books and authors. In so doing they have greatly expanded the scope of my reading, and helped me, at just the right time, to range still further, here, from the intellectual village in which I grew up.

This book is dedicated, hook, line, and sinker, to the memory of Kyle Tracker Brown (19712007).

Paris, September 2014

A Note on Citations and Terminology

Unless otherwise indicated, translations from original-language texts are our own. In cases where there is an authoritative or influential English edition of a given text, this text is cited rather than the original non-English edition. Thus for example Pierre Gassendi, Franois Bernier, and J. F. Blumenbach are cited from period translations (or, in the last case, a later nineteenth-century translation), and thus we are reading them more or less in the same words an English-language reader would have read them in the era of their greatest influence. An attempt has been made to avoid anachronism and to stay true to actors categories, both in our own translations of citations and in the analysis that follows. There are important debates in and beyond scholarly circles about the suitability of the terms indigenous, New World, and native for describing the Americas and their original inhabitants. With sensitivity to the issues raised in these debates, these and related terms have nonetheless been retained, in the hope of using them as a conceptual conduit to the way the encounter with this half of the world was experienced and thought by early modern Europeans. One area in which the respect for actors categories poses considerable difficulties is in the discussion of racial categories. Terms such as Negro and Moor have been retained in citations, and when they occur in subsequent analysis they are wrapped in quotation marks that simultaneously function as scare quotes as well as indicating a classic use/mention distinction: these are never our own terms, but always refer back to a historical author under discussion. As for black, white, and related terms, these are used without quotation marks, though with a certain degree of discomfort. Since a key argument of the book concerns the historical contingency of these terms, scare quotes may be understood as implied throughout.

Nature, Human Nature, & Human Difference

Introduction

I.1. N ATURE

In 1782, in the journal of an obscure Dutch scientific society, we find a relation of the voyage of a European seafarer to the Gold Coast of Africa some decades earlier. In the town of Axim in present-day Ghana, we learn, at some point in the late 1750s, David Henri Gallandat met a man he describes as a hermit and a soothsayer. His father and a sister were still alive, Gallandat relates, and lived a four-days journey inland. He had a brother who was a slave in the colony of Suriname.

On a certain understanding, there have been countless philosophers in Africa, whose status as such required no recognition by European institutions, no conferral of rank. She then condemns him to a life of sorrow:

You, Amo, are mistaken; with your vile nature

Your heart will never be content.

The goddesss judgment, or rather that of the author who created her, marks a sharp contrast with everything we know about Amos earlier life. In his university education, in the appraisal of his works of philosophy and jurisprudence, in the esteem in which he was held as a teacher at Wittenberg and Jena, there is no evidence whatsoever of a perception on the part of the Germans that his African origins, let alone his skin color and other physical features, should serve as an impediment to his leading a full and rewarding life as a thinker and as a human being. To put this point somewhat differently, there was no evidence that Amos nature (Wesen) could be judged to be something distinct from his heart (where this is understood as a poetic substitution for soul or self, and not, obviously, as a bodily organ). How exactly a persons nature came to be associated with his or her external physical features, and how therefore a persons nature could be said to be vile simply as a result of the conformation, color, size, or shape of these features, has much to do with the very history of philosophy to which Amo devoted much of his life. The question of how race came to mean nature will be the principal focus of this book.

Next page