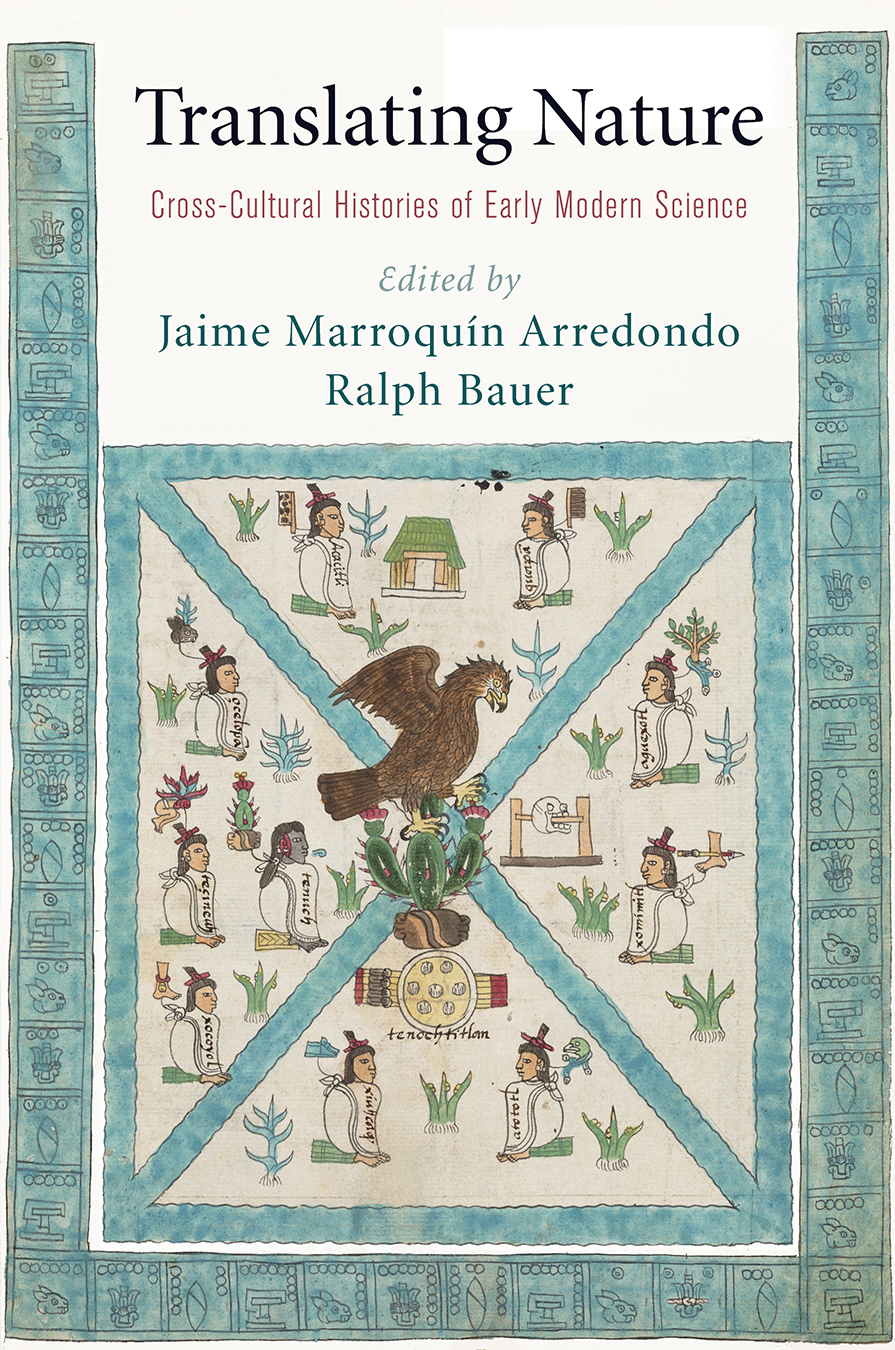

Translating Nature

THE EARLY MODERN AMERICAS

Peter C. Mancall, Series Editor

Volumes in the series explore neglected aspects of early modern history in the Western Hemisphere. Interdisciplinary in character, and with a special emphasis on the Atlantic World from 1450 to 1850, the series is published in partnership with the USC-Huntington Early Modern Studies Institute.

Translating Nature

Cross-Cultural Histories of Early Modern Science

EDITED BY

Jaime Marroqun Arredondo

and Ralph Bauer

Copyright 2019 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-8122-5093-0

Contents

Ralph Bauer and Jaime Marroqun Arredondo

Juan Pimentel

Jaime Marroqun Arredondo

Luis Millones Figueroa

Daniela Bleichmar

Marcy Norton

Sarah Rivett

Ralph Bauer

John Slater

Sara Miglietti

Christopher Parsons

Ruth Hill

William Eamon

Ralph Bauer and Jaime Marroqun Arredondo

The history of modern science has often been told as the history of discoverydiscovery in the sense of the finding of new facts and things by empirical means that overturns traditional or received conceptions of nature and the universe. The so-called discovery of America by Europeans in the fifteenth century has hereby become the paradigm of modern scientific discovery per se. The classic formulation of this was perhaps the declaration by English statesman and natural philosopher Francis Bacon in the early seventeenth century that Christopher Columbuss discovery of America had announced the coming of a new world of science beyond the book-bound circle of knowledge of the Scholastics. In this new world of science, knowledge would be gained not through the study of books (what Bacon called received philosophy), syllogistic reason, or dialectic disputation but instead by the discovery of the secrets of nature through direct observation and empirical experimentation. As William Eamon aptly notes in the afterword to the present volume, translation often precedes discovery, and in turn discovery is perhaps best characterized as an attribution. By focusing on translation, the history of science can better reckon with its truly global nature and also with the historical reality that scientific discoveries have always had quite different meanings and effects for peoples and ecosystems, often depending on their geopolitical proximity or remoteness from the hegemonic centers of economic, military, and scientific power.

This collection proposes to rethink the history of early modern science as a history not of discovery but of translation. Adopting a transcultural hermeneutics, the chapters assembled here pose the question of what role translation played not only in the history of early modern knowledge but also in the emergence of the modern (empiricist) idea of scientific discovery per se. By emphasizing the role that translation played in the history of early modern science, this volume means to highlight the contributions made by the knowledge of othersthose whose knowledge has often been erased in a historiography of science predicated on a logic of discoverymainly Native Americans and Catholic Iberians.

This volume thus contributes to current scholarship in the history of science that has challenged the notion of a scientific revolution that allegedly occurred in seventeenth-century Great Britain as the result of a radical break with tradition. But while historians have recently emphasized the considerable continuities of seventeenth-century natural philosophy with its medieval and Renaissance pasts, All too often, it is thereby forgotten that the translation and dissemination of Aristotelian and Arabic naturalism had Iberia as one of its main centers, that the Protestant Reformation was not the only (or even the earliest) reformation, and that the Catholic world, like its Protestant counterpart, was heir to the nominalist, Scotist, neo-Thomist, and humanist currents that gave rise to modern science.

There is now a growing body of scholarship countering the historiographic legacy of the Black Legend by asserting the evident modernity of sixteenth-century Spanish imperial knowledge production.the extent to which these institutions communicated with and learned from each other beyond national, imperial, and linguistic borders has not yet been fully considered. Her case in point is the history of climate theory during the seventeenth century, which, she shows, cannot be understood in isolation of any single one of these centers of knowledge production and must be seen in the context of their engagement with methodologies and ideas derived from Spanish travel accounts and natural histories written in the Americas.

One of our claims in this volume is thus that the epistemic developments that led to Francis Bacons programmatic elaboration of a new science were already a crucial part of the Iberian and, in general, Catholic scientific traditions emerging from their encounters with Native American ones. Nobody was more keenly aware of this than Bacon himself. He openly admired the sustained and extensive networks of Spanish imperial knowledge production, writing in his The Interpretation of Nature that an implementation of his proposals for collaborative, corporate, and state-sponsored production of knowledge leadeth us to an administration of knowledge in some such order and policy as the king of Spain in regard of his great dominions useth in state; who though he hath particular councils of State or last resort, that receiveth the advertisements and certificates from all the rest. One of the most important Spanish centers of this administration of knowledge admired by Bacon was the Casa de Contratacin (House of Trade), the clearinghouse in Seville instituted for the gathering and management of all information about the New World. In The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques & Discoveries of the English Nation (1598), Richard Hakluyt described the creation of the Spanish House of Trade in Seville:

[T]he late Emperour Charles the fifth, considering the rawness of his Seamen, and the manifolde shipwracks which they systeyened in passing and repassing betweene Spaine and the West Indies, with an high reach and great foresight, established not onely a Pilote Major, for the examination of such as sought to take charge of ships in that voyage, but also founded a notable Lecture of the Art of Navigation, which is read to this day in the Contractation house at Sivil. The readers of which Lecture have not only carefully taught and instructed the Spanish Mariners by word of mouth, but also have published sundry exact and worthy treatises concerning Marine causes, for the direction and incouragement of posteritie. The learned works of three of which readers, namely of Alonso de Chavez, of Hieronymo de Chavez,