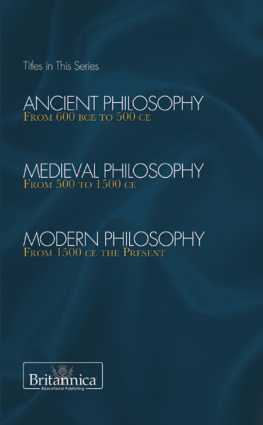

The History of Philosophy

MEDIEVAL

PHILOSOPHY

FROM 500 TO 1500 CE

EDITED BY BRIAN DUIGNAN, SENIOR EDITOR, PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION

Published in 2011 by Britannica Educational Publishing

(a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.)

in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010.

Copyright 2011 Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Educational Services materials copyright 2011 Rosen Educational Services, LLC.

All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services.

For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor

J.E. Luebering: Senior Manager

Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control

Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies

Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor

Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor

Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition

Brian Duignan: Senior Editor, Philosophy and Religion

Rosen Educational Services

Alexandra Hanson-Harding: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager

Matthew Cauli: Designer, Cover Design

Introduction by Brian Duignan

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Medieval philosophy : from 500 to 1500 ce / edited by Brian Duignan. 1st ed.

p. cm. -- (The history of philosophy)

In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61530-244-4 (eBook)

1. Philosophy, Medieval. I. Duignan, Brian.

B721.M459 2011

189dc22

2010008836

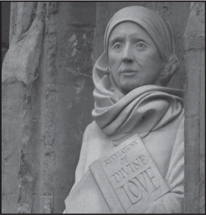

On the cover:Thomas Aquinas Hulton Archive/Getty Images

On :Medieval manuscript showing a page from the works of Albertus Magnus DEA/G. Dagli Orti/De Agostini/Getty Images

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

This 14th century painting shows, from left to right, Boethius, St. John Damascene, St. Dionysus the Areopagite (Pseudo-Dionysis), and St. Augustine. The figures behind them represent (left to right) Practical Theology, Hope, Faith, and Charity. Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy/The Bridgeman Art Library/Getty Images

A ccording to a view that was once conventional among historians, the European Middle Ages was an enormous setback to the intellectual progress of Western civilization. After the Western Roman Empire fell to invading barbarian armies in about 500 CE, most of the intellectual achievements of the Greco-Roman worldin philosophy, science, technology, art, literature, law, and governmentwere lost, forgotten, or destroyed, and Europe entered a millennium-long period (lasting to 14001500 CE) of intellectual and material decay. During much of this time, these scholars claimed, the vast majority of the European population lived in ignorance, superstition, poverty, and brutishness; virtually the only literate people on the continent were churchmen. Even the few universities, founded from the 11th century, reflected the continued stagnation of European society. The scholarship conducted in them was stale and unoriginal, consisting of dry commentaries on ancient texts and endless debate on insignificant problemsepitomized by the overdeveloped angelology (the study of the nature of angels) of the 13th century.

Philosophy throughout the Middle Ages, according to this view, was hampered, if not completely thwarted, by the imperative of conformity to the doctrines of the Roman Catholic Church. The role of philosophy was to justify or make rational sense of these doctrines using ancient concepts and methods as they were then understood. In later centuries the terms Scholasticism and Scholastic, referring to the philosophy of the schoolmen, were used in a justly pejorative sense to suggest pedantry, obsessive formalism, obscurity, and slavish adherence to intellectual authority.

Such was the common perception of medieval society and philosophy until about the mid-20th century. But it is now regarded as fundamentally mistaken. To be sure, many intellectual and artistic treasures of the ancient world were lost during the early Middle Ages (the period from 500 to about 1000 CE), but many also were preserved, notably through the painstaking efforts of monastic copyists. (Even much of what was lost did not actually disappear but was merely inaccessible, because almost no one could read Greek.) Although it is fair to say that the first few centuries of the Middle Ages were intellectually stagnant, the ensuing Carolingian period, named for the Frankish king and emperor Charlemagne (747814 CE) and his immediate successors, was marked by a renewal of Latin education and scholarship, as well as by creative developments in architecture and the visual arts. During a second and much broader intellectual revival in the 11th and 12th centuries, the number monastic, ecclesiastical, cathedral, and private schools increased substantially.

Philosophy too was much richer than the conventional view assumed. Although most of its practitioners were theologians, and although most of them regarded philosophy as a tool for understandingnot challengingthe basic tenets of the Christian faith, in their hands ancient philosophy was developed and transformed in novel and sophisticated ways, and eventually it was applied to problems well beyond the realm of religion.

The medieval period in the history of Western philosophy is now recognized for its outstanding contributions

to metaphysics, logic, and ethics, as well as to the philosophy of religion. In metaphysics, medieval philosophers explored the problem of universals (the question of whether there are independent entities corresponding to general terms such as red or round) in unprecedented depth, developing theoretical alternatives that remain influential in contemporary discussions, and they produced intricate solutions to the problem of free will (the problem of reconciling human free will and divine foreknowledge of human actions). In logic, the medieval period is regarded as one of the three most productive and original in the history of the disciplinethe other two being the ancient and Hellenistic periods and the late-19th to 20th centuries.

Next page