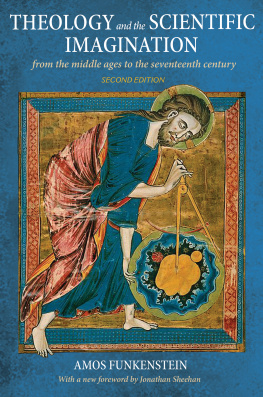

Gods Philosophers

HOW THE MEDIEVAL WORLD LAID THE FOUNDATIONS OF MODERN SCIENCE

JAMES HANNAM

ICON BOOKS

Published in the UK in 2009 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

3941 North Road, London N7 9DP

email:

www.iconbooks.co.uk

This electronic edition published in 2009 by Icon Books

ISBN: 978-1-84831-158-9 (ePub format)

ISBN: 978-1-84831-159-6 (Adobe ebook format)

Printed edition (ISBN: 978-1-84831-070-4)

Sold in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

7477 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asia

by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road

Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

This edition published in Australia in 2009

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd, PO Box 8500,

83 Alexander Street, Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in Canada by

Penguin Books Canada,

90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700,

Toronto, Ontario M4P 2YE

Text copyright 2009 James Hannam

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any

means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset by Marie Doherty

To Vanessa

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

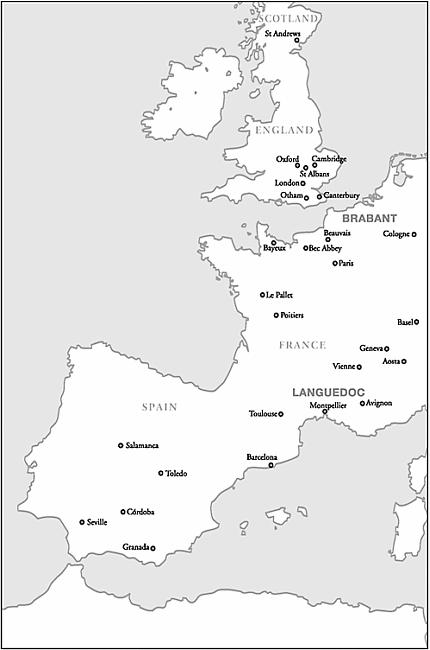

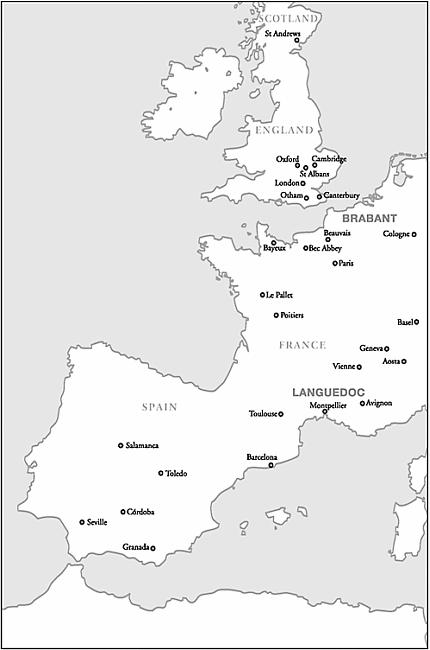

Map of medieval Europe

INTRODUCTION

The Truth about Science in the Middle Ages

The most famous remark made by Sir Isaac Newton (1642 1727) was: If I have seen a little further then it is by standing on the shoulders of giants. Even fewer are aware that Newtons science also has its roots embedded firmly in the Middle Ages. This book will show just how much of the science and technology that we now take for granted has medieval origins.

The achievements of medieval science are so little known today that it might seem natural to assume that there was no scientific progress at all during the Middle Ages. The period has had a bad press for a long time. Writers use the adjective medieval as a synonym for brutality and uncivilised behaviour. Recently, the word has affixed itself to the Taliban of Afghanistan whom commentators routinely describe as throwbacks to the Middle Ages, if not the Dark Ages. Even historians, who should know better, still seem addicted to the idea that nothing of any consequence occurred between the fall of the Roman Empire and the Renaissance. In 1988, Daniel Boorstins history of science The Discoverers referred to the Middle Ages as the great interruption to mankinds progress. William Manchester, in his 1993 book A World Lit Only by Fire, described the period as a mlange of incessant warfare, corruption, lawlessness, obsession with strange myths and an almost impenetrable mindlessness. Charles Freeman wrote in The Closing of the Western Mind (2002) that this was a period of intellectual stagnation. He continued, It is hard to see how mathematics, science, or their associated disciplines could have made any progress in this atmosphere.

Closely coupled to the myth that there was no science worth mentioning in the Middle Ages is the belief that the Church held back what meagre advances were made. The idea that there is an inevitable conflict between faith and reason owes much of its force to the work of nineteenth-century propagandists such as the Englishman Thomas Huxley (182595) and the American John William Draper (181182). Huxley famously declared: Extinguished theologians lie about the cradle of every science, as the strangled snakes beside that of Hercules. Draper was a participant in the notorious debate on evolution between Huxley and the bishop of Oxford, Samuel Wilberforce (180573), in 1860, when the question arose of whether Huxley was descended from an ape on his mothers or fathers side. Draper wrote the massively influential History of the Conflict between Religion and Science, which cemented the conflict hypothesis into the public imagination.

More recently, we have seen a real-life conflict between evolution and creationism. Conservative Christians and Muslims have launched an all-out assault on Darwinism. As this phenomenon shows, it is certainly true that particular religious doctrines can be in conflict with scientific theories. However, it does not follow that such hostility is inevitable. During the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church actively supported a great deal of science, but it also decided that philosophical speculation should not impinge on theology. Ironically, by keeping philosophers focused on nature instead of metaphysics, the limitations set by the Church may even have benefited science in the long term. Furthermore and contrary to popular belief, the Church never supported the idea that the earth is flat, never banned human dissection, never banned zero and certainly never burnt anyone at the stake for scientific ideas. The most famous clash between science and religion was the trial of Galileo Galilei (15641642) in 1633. Academic historians are now convinced that this had as much to do with politics and the Popes self-esteem as it did with science. The trial is fully explained in the last chapter of this book, in which we will also see how much Galileo himself owed to his medieval predecessors.

The denigration of the Middle Ages began as long ago as the sixteenth century, when humanists, the intellectual trendsetters of the time, started to champion classical Greek and Roman literature. They cast aside medieval scholarship on the grounds that it was convoluted and written in barbaric Latin. So people stopped reading and studying it. The cudgels were subsequently taken up by English writers such as Francis Bacon (15611626), Thomas Hobbes (1588 1679) and John Locke (16321704). The waters were muddied further by the desire of these Protestant writers not to give an ounce of credit to Catholics. It suited them to maintain that nothing of value had been taught at universities before the Reformation. Galileo, who thanks to his trial before the Inquisition was counted as an honorary Protestant, was about the only Catholic natural philosopher to be accorded a place in English-language histories of science.

In the eighteenth century, French writers like Voltaire (16941778) joined in the attack. They had their own issues with the Catholic Church in France, which they derided as reactionary and in cahoots with the absolutist monarchy. Voltaire and his fellow philosophes lauded progress in reason and science. They needed a narrative to show that mankind was moving forward, and the story they produced was intended to show the Church in a bad light. Medieval philosophy, bastard daughter of Aristotles philosophy badly translated and understood, wrote Voltaire, had caused more error for reason and good education than the Huns and the Vandals. But now, DAlembert said, in his own time rational men could throw off the yoke of religion.