Table of Contents

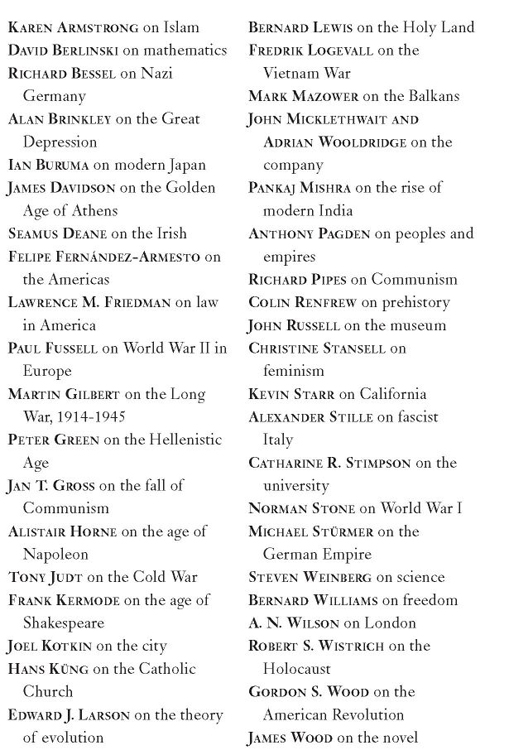

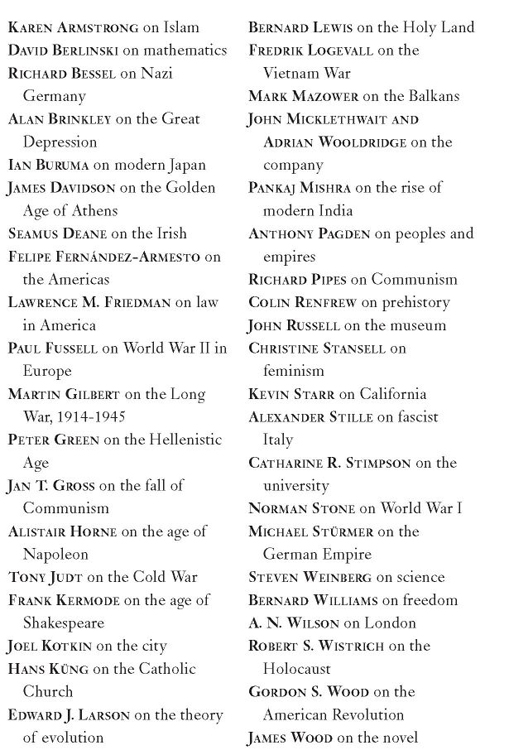

Modern Library Chronicles

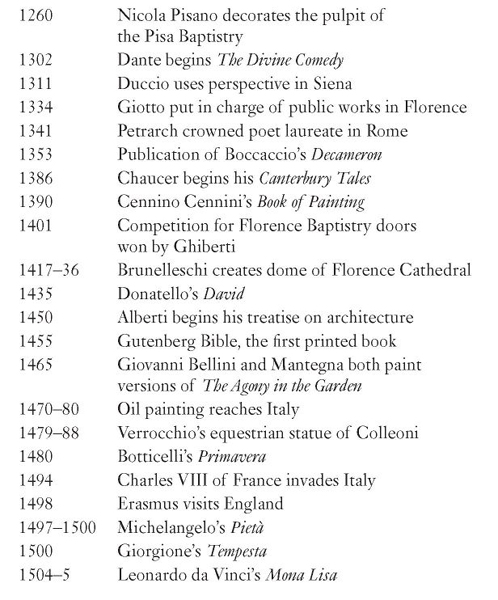

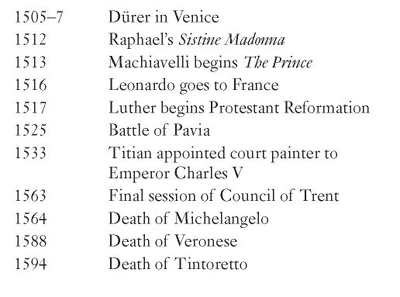

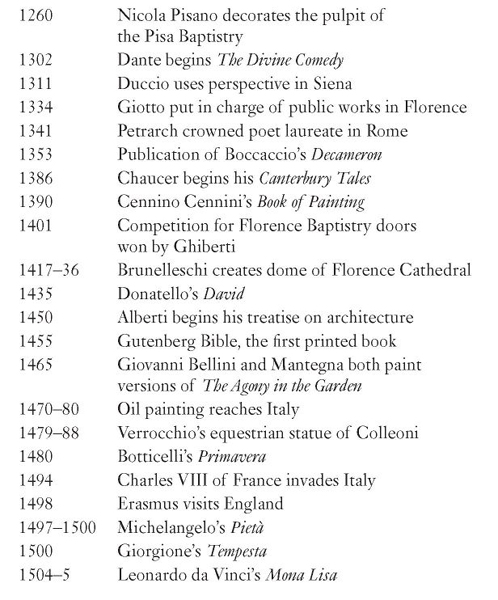

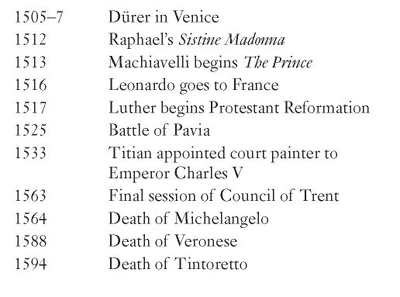

CHRONOLOGY

Please note that some dates are approximate or speculative.

PART 1

THE HISTORICAL AND ECONOMIC BACKGROUND

The past is infinitely complicated, composed as it is of events, big and small, beyond computation. To make sense of it, the historian must select and simplify and shape. One way he shapes the past is to divide it into periods. Each period is made more memorable and easy to grasp if it can be labeled by a word that epitomizes its spirit. That is how such terms as the Renaissance came into being. Needless to say, it is not those who actually live through the period who coin the term, but later, often much later, writers. The periodization and labeling of history is largely the work of the nineteenth century. The term Renaissance was first prominently used by the French historian Jules Michelet in 1858, and it was set in bronze two years later by Jacob Burckhardt when he published his great book The Civilization of the Renaissance inItaly. The usage stuck because it turned out to be a convenient way of describing the period of transition between the medieval epoch, when Europe was Christendom, and the beginning of the modern age. It also had some historical justification because, although the Italian elites of the time never used the words Renaissance or Rinascimento, they were conscious that a cultural rebirth of a kind was taking place, and that some of the literary, philosophical and artistic grandeur of ancient Greece and Rome was being re-created. In 1550 the painter Vasari published an ambitious work, TheLives of the Artists, in which he sought to describe how this process had taken place, and was continuing, in painting, sculpture and architecture. In comparing the glories of antiquity with the achievements of the present and recent past in Italy, he referred to the degenerate period in between as the middle ages. This usage stuck too.

Thus a nineteenth-century term was used to mark the end of a period baptized in the sixteenth century. But when exactly, in real chronological terms, did this end of one epoch and beginning of another occur? Here we come to the first problem of the Renaissance. Historians have for long agreed that what they term the early modern period of European history began at the end of the fifteenth century and the beginning of the sixteenth, though they date it differently in different countries. Thus, Spain entered the early modern age in 1492, when the conquest of Granada was completed with the expulsion of the Moors and the Jews, and Christopher Columbus landed in the Western Hemisphere on the instructions of Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand. England entered the period in 1485, when the last Plantagenet king, Richard III, was killed at Bosworth and the Tudor dynasty acquired the throne in the person of Henry VII. France and Italy joined Spain and England by virtue of the same event, in 1494, when the French king Charles VIII invaded Italy. Finally, Germany entered the new epoch in 1519, when Charles V united the imperial throne of Germany with the crown of Spain and the Indies. However, by the time these events took place, the Renaissance was already an accomplished fact, in its main outlines, and moving swiftly to what art historians term the High Renaissance, its culmination. Moreover, the next European epoch, the Reformation, usually dated by historians from Martin Luthers act of nailing his ninety-five theses to the door of the church in Wittenberg in 1517, had already begun. So we see that the connection between the Renaissance and the start of the early modern period is more schematic than chronologically exact.

The next problem, then, is defining the chronology of the Renaissance itself. If the term has any useful meaning at all, it signifies the rediscovery and utilization of ancient virtues, skills, knowledge and culture, which had been lost in the barbarous centuries following the collapse of the Roman Empire in the West, usually dated from the fifth century A.D. But here we encounter another problem. Cultural rebirths, major and minor, are a common occurrence in history. Most generations, of all human societies, have a propensity to look back on golden ages and seek to restore them. Thus the long civilization of ancient Egypt, neatly divided by modern archaeologists into the Old Kingdom, the Middle Kingdom and the New Kingdom, was punctuated by two collapses, termed intermediate periods, and both the Middle and the New kingdoms were definite and systematic renaissances. Over three millennia, the cultural history of ancient Egypt is marked by conscious archaisms, the deliberate revival of earlier patterns of art, architecture and literature to replace modes recognized as degenerate. This was a common pattern in ancient societies. When Alexander the Great created a world empire in the fourth century B.C., his court artists sought to recapture the splendor of fifth-century Athenian civilization. So Hellenistic Greece, as we call it, witnessed a renaissance of classic values.

Rome itself periodically attempted to recover its virtuous and creative past. Augustus Caesar, while creating an empire on the eve of the Christian period, looked back to the noble spirit of the Republic, and even beyond it to the very origins of the city, to establish moral and cultural continuities and so legitimize his regime. The court historian Livy resurrected the past in prose, the court epic poet Virgil told the story of Romes divinely blessed origins in verse. The empire was never quite so self-confident as the Republic, subject as it was to the whims of a fallible autocrat, rather than the collective wisdom of the Senate, and it was always looking over its shoulder at a past that was more worthy of admiration and seeking to resurrect its qualities. The idea of a republican renaissance was never far from the minds of Romes imperial elites.

Naturally, after the fall of the Western empire in the fifth century A.D., the longing for the recovery of the majestic past of Rome intensified among the fragile or semibarbarous societies that succeeded the imperial order. In the Vatican Library there is a codex, known as the Vatican Virgil, which dates from the fifth or sixth century. It is written in a monumental Capitalis Rustica, a self-conscious attempt to revive the Roman calligraphic majuscule, which had largely fallen out of use during the degenerate times of the third and fourth centuries. The artist-scribe, perhaps from Ravenna, who illustrated the text with miniatures, including one of Virgil himself, evidently had access to high-quality Roman work from a much earlier date, which he imitated and simplified to the best of his ability. Here is an early example of an attempted renaissance of lost Roman skills. There were many such.

Next page