Contents

Landmarks

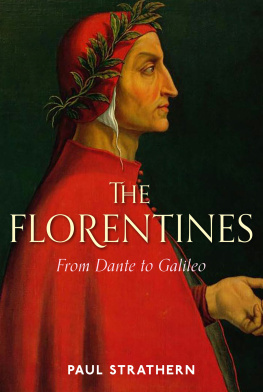

THE FLORENTINES

Also by Paul Strathern

The Borgias

Death in Florence

Spirit of Venice

The Artist, the Philosopher and the Warrior

Napoleon in Egypt

The Medici

THE

FLORENTINES

From Dante to Galileo

PAUL STRATHERN

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright Paul Strathern, 2021

The moral right of Paul Strathern to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978-1-78649-872-4

Trade paperback ISBN: 978-1-83895-385-0

E-book ISBN: 978-1-78649-873-1

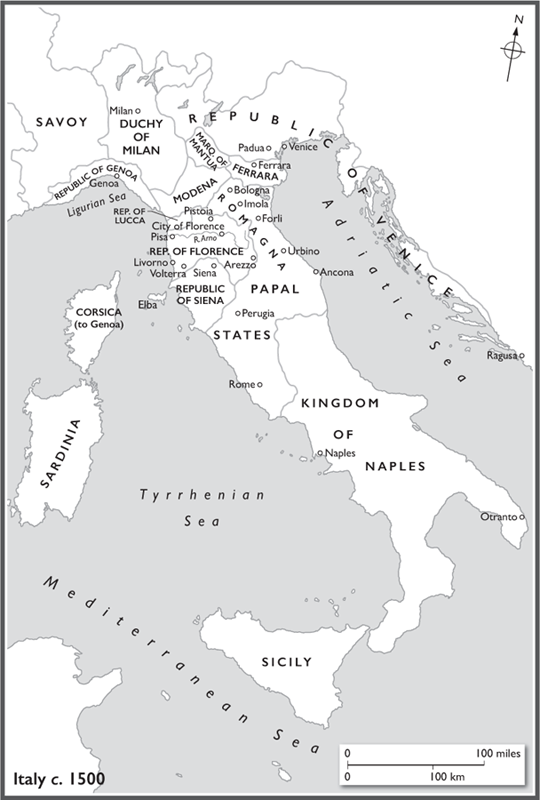

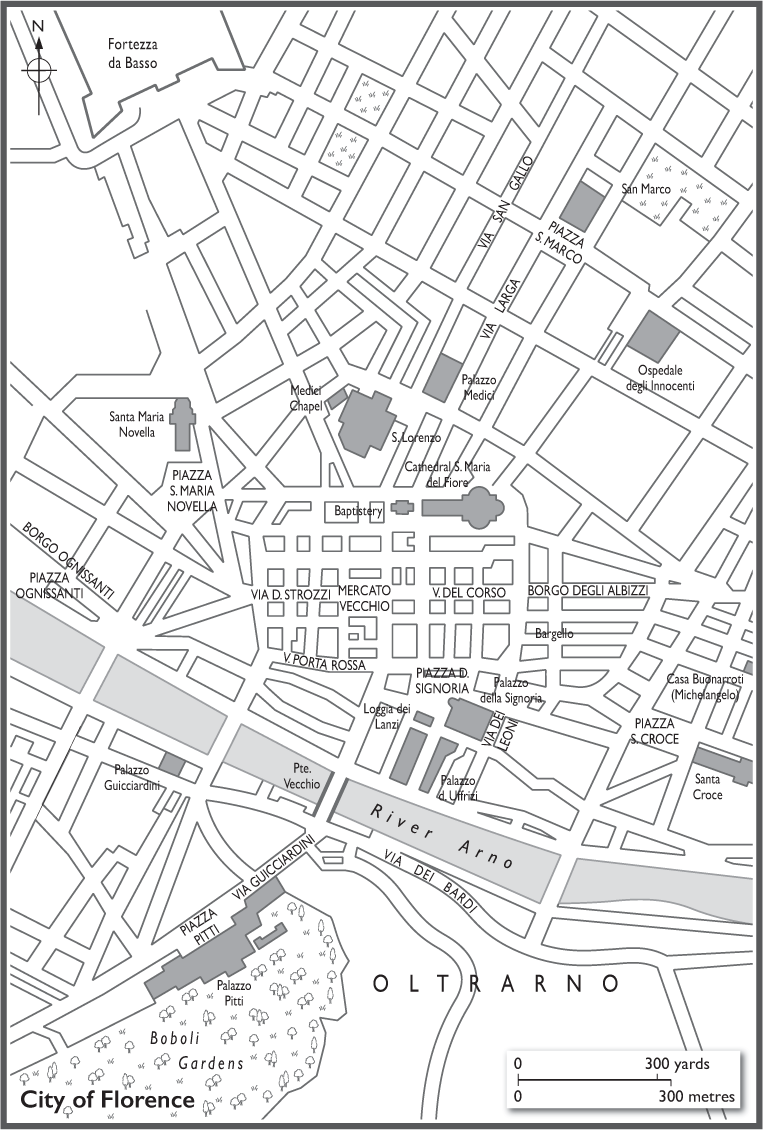

Map artwork by Jeff Edwards

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

To

Arabella

CONTENTS

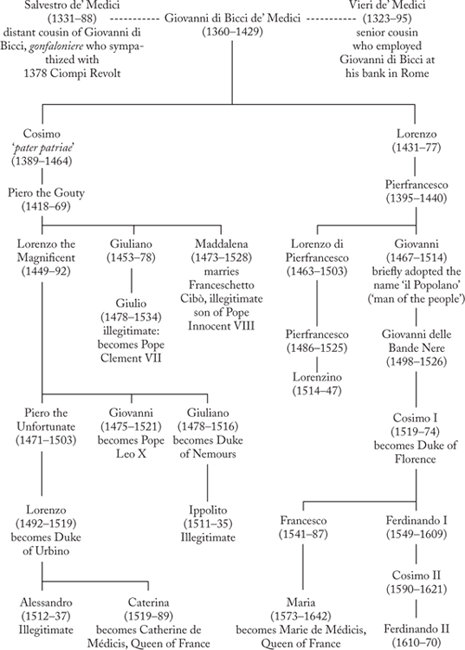

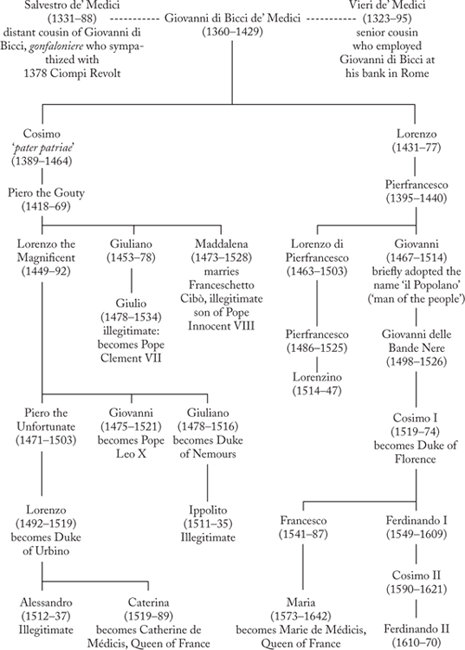

MEDICI FAMILY TREE

PROLOGUE

B ETWEEN THE BIRTH OF Dante in 1265 and the death of Galileo in 1642, something happened which would transform the entire culture of western civilization. Painting, sculpture and architecture would all visibly change in such a striking fashion that there could be no going back on what had taken place. Likewise, the thought and self-conception of western European humanity would take on a completely new aspect. Sciences would be born, or emerge in an entirely new guise. Part of this cultural transformation would be influenced by the rediscovery of the pre-Christian literature of Ancient Greece and Rome, but much of it would result from how the novelty of this earlier essentially pagan outlook came into conflict with, and was assimilated by, the society in which it was rediscovered.

The collapse of the Roman Empire just under a millennium previously had left Europe largely in a state of historical and intellectual desolation often referred to as the Dark Ages, with the few persisting centres of learning mainly confined to isolated monasteries. Gradually, with the encouragement of Christianity, this dark age evolved into the medieval world. Consequently, the combination of intellect and faith came to be regarded as such a precious commodity, preserving civilization itself, that a widespread orthodoxy prevailed in order to protect it. However, over the centuries this orthodoxy permeated all aspects of life to the point where it dominated intellectual debate, and a state of cultural stasis began to prevail.

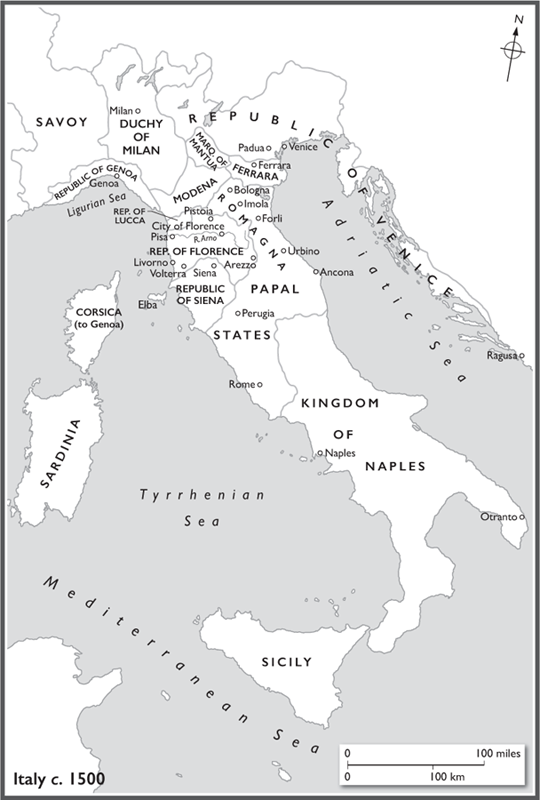

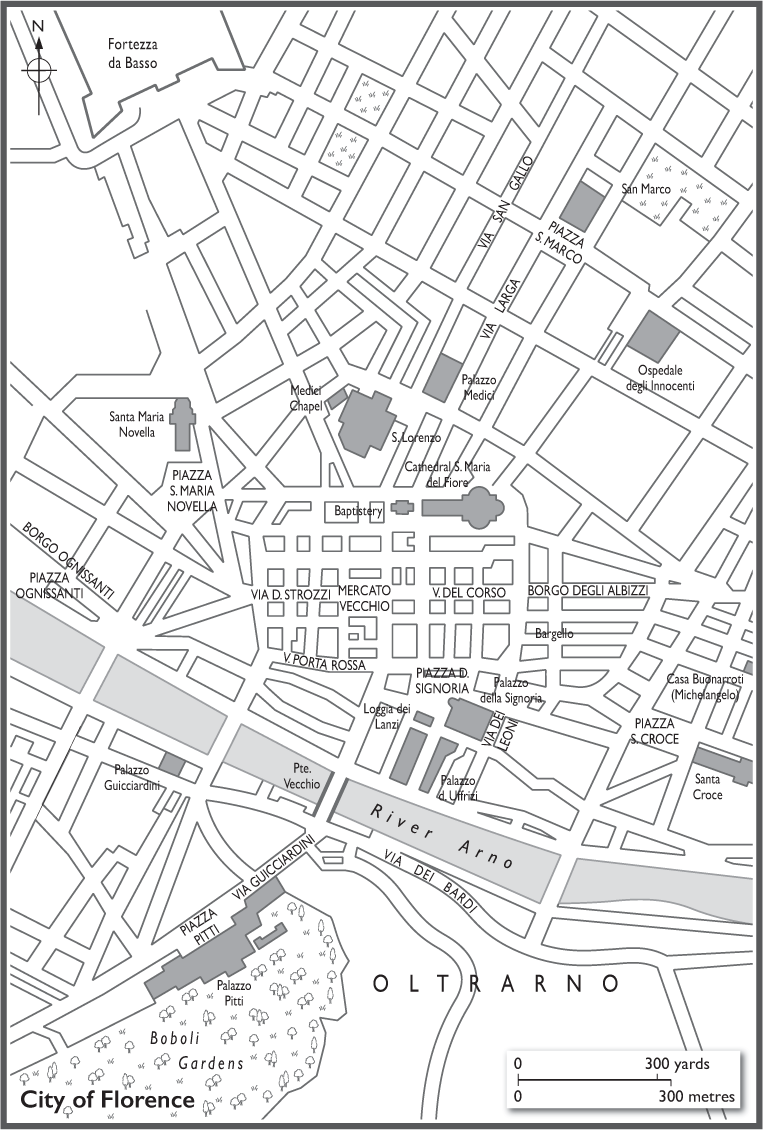

The ideas which broke this mould largely began, and continued to flourish, in the city of Florence, in the region of Tuscany in northern central Italy. Such novel concepts, which placed an increasing emphasis on the development of our common humanity rather than otherworldly spirituality would coalesce into what came to be known as humanism. As its name suggests, this philosophical attitude emphasizes our individual humanity and its central place in our lives, rather than relying upon divine providence and concentrating on metaphysical matters. Its founding insight can be seen in the assertion by the fifth-century BC Greek philosopher Protagoras: Man is the measure of all things. As such, humanism led to an increased self-understanding, and a radical extension of our psychological self-knowledge. We gained a clearer picture of ourselves, and in doing so were inclined to seek more rational solutions to our problems rather than reverting to the power of prayer.

This philosophical outlook would eventually spread across Italy, yet wherever it took root it would retain an element essential to its origin. And as it spread further across Europe, this element would remain. Inevitably, other ingredients also entered this rich mix. Amongst the trading cities of northern Europe humanism would flourish and develop, absorbing local characteristics. In less cosmopolitan kingdoms it would take on a more static element of empty show. At the same time, more abstemious, narrow-minded populations could not, or would not, tolerate such ostentation and luxury. Despite such apparent resistance, elements of the new humanism would also subtly permeate even their repressive mental outlook. This was in many ways the period in which the modern era began. The way we think, the way in which we regard ourselves, our modern notion of progress these, and much more, originated from the humanist era.

Transformations of human culture throughout western history have remained indelibly stamped by their origins, no matter how they have evolved beyond these local beginnings. The Reformation would always retain something of central and northern Germany in its many variations. The Industrial Revolution soon outgrew its British origins, yet also retained something of its original template. Closer to the present, the Digital Revolution which began in Silicon Valley remains indelibly coloured by its Californian roots. It is my aim to show how Florence, and the Florentines, played a similar role in the nurture and evolution of the Renaissance.

CHAPTER 1

DANTE AND FLORENCE

I N 1308, THE EXILED Florentine poet Dante Alighieri described how, midway through his life, he found himself lost amidst a dark wood, with no sign of a path. He had no idea how he had arrived where he was. His mind was fogged; it was as if he had woken from a deep slumber. After walking for a while, filled with trepidation, he came to the foot of a hill at the end of a valley. Raising his gaze, he saw the high upland bathed in the rays of the dawning sun. He began to climb the barren slope, finally pausing for a while to rest his weary limbs. Not long after restarting, he found his way blocked by a gambolling leopard, its dappled fur rippling as it skipped before his feet. By now the sun had begun to rise in the heavens, and the sight of this fine frisking beast in the morning sunlight inspired Dante with hope. But this suddenly vanished when he caught sight of a roaring lion charging towards him. No sooner had he escaped from this fearful beast than he encountered a lean and slavering, hungry she-wolf, which caused him to retreat in terror down the slope, back towards the dark silence of the sunless wood. As he stumbled headlong downwards, he saw before him a ghostly form.

Help me! cried Dante. Whatever you are man or spirit.

The shadowy figure replied, No, I am not a man. Though once I was. I lived in Rome, during the reign of the good Augustus Caesar, in a time of false and lying gods. I was a poet, who sang of Troy