Contents

About the Author

Paul Strathern studied philosophy at Trinity College, Dublin. He is a Somerset Maugham prize-winning novelist; the author of the series of books Philosophers in 90 Minutes and The Big Idea: Scientists who Changed the World; and most recently, Mendeleyevs Dream (shortlisted for the Aventis Science Book Prize), Dr Strangeloves Game: A History of Economic Genius and Napoleon in Egypt. He lives in London.

About the Book

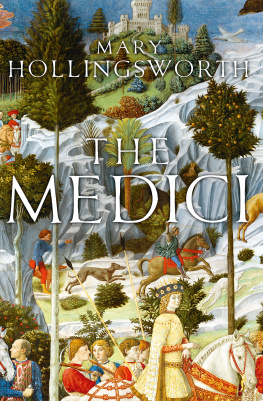

A dazzling history of the modest family which rose to become one of the most powerful in Europe, The Medici is a remarkably modern story of power, money and ambition. Against the background of an age which saw the rebirth of ancient and classical learning, Paul Strathern explores the intensely dramatic rise and fall of the Medici family in Florence, as well as the Italian Renaissance which they did so much to sponsor and encourage.

Strathern also follows the lives of many of the great Renaissance artists with whom the Medici had dealings, including Leonardo, Michelangelo and Donatello; as well as scientists like Galileo and Pico della Mirandola; and the fortunes of those members of the Medici family who achieved success away from Florence, including the two Medici popes and Catherine de Mdicis, who became Queen of France and played a major role in that country through three turbulent reigns.

The Medici

Godfathers of the Renaissance

Paul Strathern

to Kathleen

Acknowledgements

I WOULD PARTICULARLY like to acknowledge the assistance provided to me in the writing of this book by Jrg Hensgen, whose meticulous editing contributed so much to the style and content of this work. I would also like to thank his readers, whose advice on matters of fact proved invaluable. Any remaining infelicities of style or content remain my own doing.

I would also like to take this opportunity to offer long overdue thanks to the ever-helpful and friendly staff of the British Library, and the Science Museum Library on Imperial College Campus, who have for many years assisted me in my researches.

P. S.

Illustrations

COLOUR PLATES

Cosimo de Medici, painting by Jacopo da Pontormo, c. 151819, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence (akg-images/Erich Lessing).

Federigo da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, painting by Piero della Francesca, c. 146075, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence (akg-images/Erich Lessing).

Madonna and Child by Fra Filippo Lippi, 1452, Palazzo Pitti, Florence (akg-images/Orsi Battaglini).

Primavera (Allegory of Spring) by Sandro Botticelli, c. 147778, Galleria degli Uffizi (akg-images/Erich Lessing).

Pope Leo X, with Cardinals Luigi de Rossi and Giulio de Medici by Raphael, 151718, Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence (akg-images/Rabatti-Domingie).

The Last Judgement by Michelangelo Buonarroti, 153641, Sistine Chapel, Vatican, Rome (akg-images).

Marie de Mdicis, painting by Peter Paul Rubens, c. 162225, Museo del Prado, Madrid (akg-images).

Ferdinando II de Medici, painting by Justus Sustermans, Galleria Palatina, Florence ( 1990Galleria Palatina/Photo Scala, Florence; courtesy of the Ministero Beni e Att. Culturali).

BLACK AND WHITE ILLUSTRATIONS

@vintagebooks

penguin.co.uk/vintage

1

Ancient Beginnings

THE MEDICI FAMILY is said to have been descended from a knight called Averardo, who fought for Charlemagne during his conquest of Lombardy in the eighth century. According to Medici family legend, Averardo was travelling through the Mugello, a remote valley near Florence, when he heard tell of a giant who was terrorising the neighbourhood. Averardo went in search of the giant, and challenged him. As they faced each other, the giant swung his mace. Averardo ducked and the iron balls from the giants mace smashed into his shield; but eventually Averardo managed to slay the giant. Charlemagne was so impressed when he heard of Averardos feat that he decreed that henceforth his brave knight could use his dented shield as his personal insignia.

The Medici insignia of red balls (or palle) on a field of gold is said to derive from Averardos dented shield. Others claim that the Medici were, as their name suggests, originally apothecaries dispensing medicines to the public, and that the balls of their insignia were in fact pills. This story was always denied by the Medici, and their denial is supported by historical evidence, as the medical use of pills did not become commonplace until some time after the appearance of the Medici insignia. The most likely origin of their insignia is the sign that medieval money-changers hung outside their shops, depicting coins. Money-changing was the initial Medici family business.

The legendary knight Averardo settled in the Mugello, the fertile valley of the River Sieve, which runs through the mountains twenty-five miles by road to the north-east of Florence. Even today, the region remains a picturesque spot with vineyards and olive groves either side of the curving river, beneath steep wooded hills and the mountains beyond. This isolated region of less than twenty square miles must have had an exceptional gene pool: not only did it produce the multi-talented Medici, but also the families of geniuses as disparate as Fra Angelico, Galileo and Giotto.The Medici family came from the village of Cafaggiolo, and was always to retain strong links with this spot.

Some time before the turn of thirteenth century the Medici family appears to have left Cafaggiolo to try their luck in Florence. They were not the only country people to seek their fortune in Florence at around this time, and between the mid-twelfth and mid-thirteenth centuries the population of Florence is said to have increased fivefold to more than 50,000. Medieval methods of ascertaining the population were notoriously fanciful, which leaves such figures open to question. The census-taking methods of Florence were a case in point: births were registered by the simple method of counting beans when a child was born, the family was expected to drop a bean into the local census box: black for a boy or white for a girl. However, we know that Florence experienced an unprecedented increase in population during this period, making it larger than Rome or London, though it remained smaller than the great medieval centres of Paris, Naples and Milan.

The Medici settled in the neighbourhood of San Lorenzo, clustered about the church of San Lorenzo, the earliest part of which had been consecrated in the fourth century. As a result, San Lorenzo would become the patron saint of the Medici, and some of the familys most illustrious sons would be named after him. From San Lorenzo it was just a few minutes walk to the Mercato Vecchio (Old Market), the hub of the citys commercial life (now the large central Piazza della Repubblica). Here visitors came from miles around to buy the cloth for which the city was famous, with bolts of brightly coloured material laid out on the trestle stalls, cut to measure against the customer as he bargained. Early in the morning the streets leading to this large square would be filled with the carts of farmers bringing their wares to market, the squeals of driven pigs, bleating sheep, the mooing of milk cows. Amidst the cries of the sellers and animals, there were stalls selling freshly caught fish from the Arno, slices from hooked slabs of bloody meat, varieties of cheeses, wine from the barrel. Along the walls were neatly stacked piles of coloured vegetables and fruit onions and withered greens in the spring; fennel and figs, cherries and oranges in summer; and in winter, meagre piles of earthy root vegetables. Amidst the throng of townsfolk and yokels, the mendicant friars in their threadbare robes begged from passers-by. The blare of a heralds trumpet, and the crowd would throng the entrance to the Via del Corso to watch a bloodied, stumbling criminal in rags and chains being whipped through the street amidst jeers, on his way to the Bargello and a public hanging on the morrow.