CHRISTOPHER HIBBERT

THE RISE AND FALL OF THE HOUSE OF MEDICI

FOR EVE WEISS AND IN MEMORY OF ROBERTO

Christopher Hibbert was born in Leicestershire in 1924 and educated at Radley and Oriel College, Oxford. He served as an infantry officer during the war, was twice wounded and was awarded the Military Cross in 1945. Described in the New Statesman as a pearl of biographers, he is, in the words of The Times Educational Supplement, perhaps the most gifted popular historian we have. His many highly acclaimed books include the following titles, most of which are published by Penguin: The Destruction of Lord Raglan (which won the Heinemann Award for Literature in 1962), London: The Biography of a City, The Rise and Fall of the House of Medici, The Great Mutiny: India 1857, The French Revolution, Garibaldi and His Enemies, Rome: The Biography of a City, Elizabeth I: A Personal History of the Virgin Queen, Florence: The Biography of a City, Nelson: A Personal History, George III: A Personal History and The Marlboroughs: John and Sarah Churchill 1650 1744.

Christopher Hibbert is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and an Hon. D. Litt. of Leicester University. He is married with two sons and a daughter, and lives in Henley-on-Thames.

ALTHOUGH THERE are very many books on the lives and times of the Medici, not since the appearance of Colonel G.F. Youngs two-volume work in 1909 has there been a full-length study in English devoted to the history of the whole family from the rise of the Medici bank in the late fourteenth century under the guidance of Giovanni di Bicci de Medici to the death of the last of the Medici Grand Dukes of Tuscany, Gian Gastone, in 1737. This book is an attempt to supply such a study and to offer a reliable alternative, based on the fruits of modern research, to Colonel Youngs work, which Ferdinand Schevill has described as the subjective divagations of a sentimentalist with a mind above history.

I cannot pretend to be an expert in any of the wide-ranging fields covered in the book; and I am, of course, deeply indebted to those writers and scholars upon whose publications I have been able to rely. I would like to mention in particular Sir Harold Acton, Miss Eve Borsook, Professor Eric Cochrane, Mr Vincent Cronin, Professor J.R. Hale, Dr George Holmes, Professor Lauro Martines, Marchesa Iris Origo, Marchese Ridolfi, Professor Raymond de Roover, Professor Nicolai Rubinstein and Mr Ferdinand Schevill. I am also extremely grateful to Dr Brian Moloney of the Department of Italian in the University of Leeds and to Dr George Holmes of St Catherines College, Oxford, for having read the book in proof and for having made several valuable suggestions for its improvement. Parts of the book have also been read by Signor Fabio Naldi who has been good enough to place his wide knowledge of Tuscan topography and architecture at my disposal. For their great kindness and help when I was working in Florence I want to thank Signorina Patrizia Naldi and the staffs of the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale and of the Museo di Firenze ComEra.

For their help in a variety of other ways I am much indebted to Dr Roberto Bruni, Mrs Maurice Hill, Mrs Geraldine Norman, Conte Francesco Papafava, Mrs John Rae, Mrs Joan St George Saunders, Mr Meaburn Staniland and the staffs of the British Museum, the London Library and the Bodleian Library, Oxford.

Finally I want to say how grateful I am, once again, to my friends Mr Hamish Francis and Mr George Walker for having read the proofs, and to my wife for having compiled the index.

C.H.

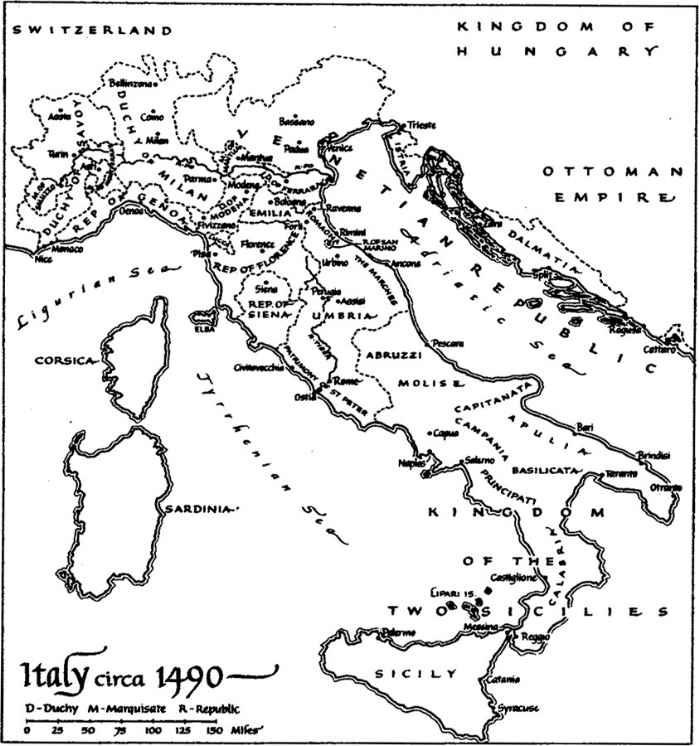

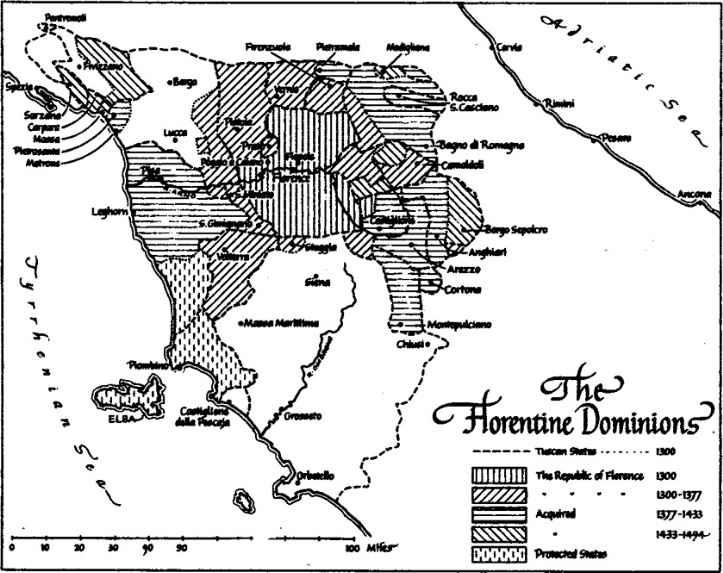

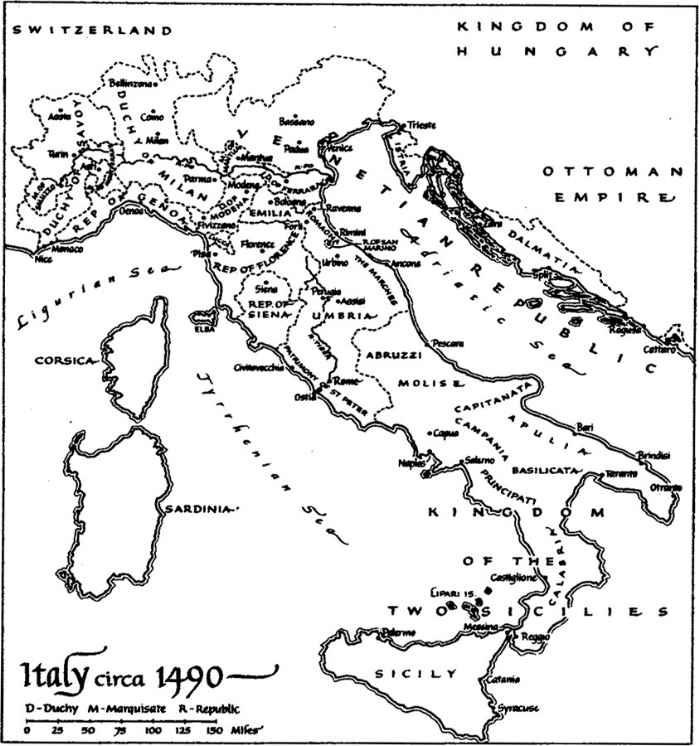

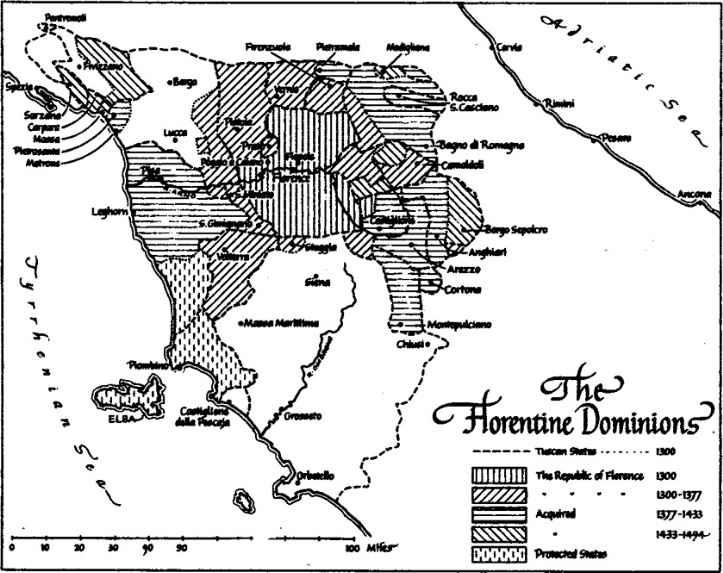

Maps and Genealogical Tables by Leo Vernon

I

FLORENCE AND THE FLORENTINES

A Florentine who is not a merchant enjoys no esteem whatever

ONE SEPTEMBER morning in 1433, a thin man with a hooked nose and sallow skin could have been seen walking towards the steps of the Palazzo della Signoria in Florence.1 His name was Cosimo de Medici; and he was said to be one of the richest men in the world. As he entered the palace gate an official came up to him and asked him to wait in the courtyard: he would be taken up to the Council Chamber as soon as the meeting being held there was over. A few minutes later the captain of the guard told him to follow him up the stairs; but, instead of being shown into the Council Chamber, Cosimo de Medici was escorted up into the bell-tower and pushed into a cramped cell known as the Alberghettino the Little Inn the door of which was shut and locked behind him. Through the narrow slit of its single window, so he later recorded, he looked down upon the city.

It was a city of squares and towers, of busy, narrow, twisting streets, of fortress-like palaces with massive stone walls and overhanging balconies, of old churches whose facades were covered with geometrical patterns in black and white and green and pink, of abbeys and convents, nunneries, hospitals and crowded tenements, all enclosed by a high brick and stone crenellated wall beyond which the countryside stretched to the green surrounding hills. Inside that long wall there were well over 50,000 inhabitants, less than there were in Paris, Naples, Venice and Milan, but more than in most other European cities, including London though it was impossible to be sure of the exact number, births being recorded by the haphazard method of dropping beans into a box, a black bean for a boy, a white one for a girl.

For administrative purposes the city was divided into four quartieri and each quartiere was in turn divided into four wards which were named after heraldic emblems. Every quartiere had its own peculiar character, distinguished by the trades that were carried on there and by the palaces of the rich families whose children, servants, retainers and guards could be seen talking and playing round the loggie, the colonnaded open-air meeting grounds where business was also discussed.

The busiest parts of the city were the area around the stone bridge, the Ponte Vecchio, which spanned the Arno at its narrowest point and was lined on both sides with butchers shops and houses;2 the neighbourhood of the Orsanmichele, the communal granary, where in summer the bankers set up their green cloth-covered tables in the street and the silk merchants had their counting-houses;3 and the Mercato Vecchio, the big square where once the Roman Forum had stood.4 Here, in the Mercato Vecchio, the Old Market, were the shops of the drapers and the second-hand-clothes dealers, the booths of the fishmongers, the bakers and the fruit and vegetable merchants, the houses of the feather merchants and the stationers, and of the candle-makers where, in rooms smoky with incense to smother the smell of wax, prostitutes entertained their customers. On open counters in the market, bales of silk and barrels of grain, corn and leather goods were exposed for sale, shielded by awnings from the burning sun. Here also out in the open barbers shaved beards and clipped hair; tailors stitched cloth in shaded doorways; servants and housewives gathered round the booths of the cooked-food merchants; bakers pushed platters of dough into the communal oven; and furniture makers and goldsmiths displayed their wares. Town-criers marched about calling out the news of the day and broadcasting advertisements; ragged beggars held out their wooden bowls; children played dice on the flagstones and in winter patted the snow into the shape of lions, the heraldic emblem of the city. Animals roamed everywhere: dogs wearing silver collars; pigs and geese rooting about in doorways; occasionally even a deer or a chamois would come running down from the hills and clatter through the square.