CONTENTS

ABOUT THE BOOK

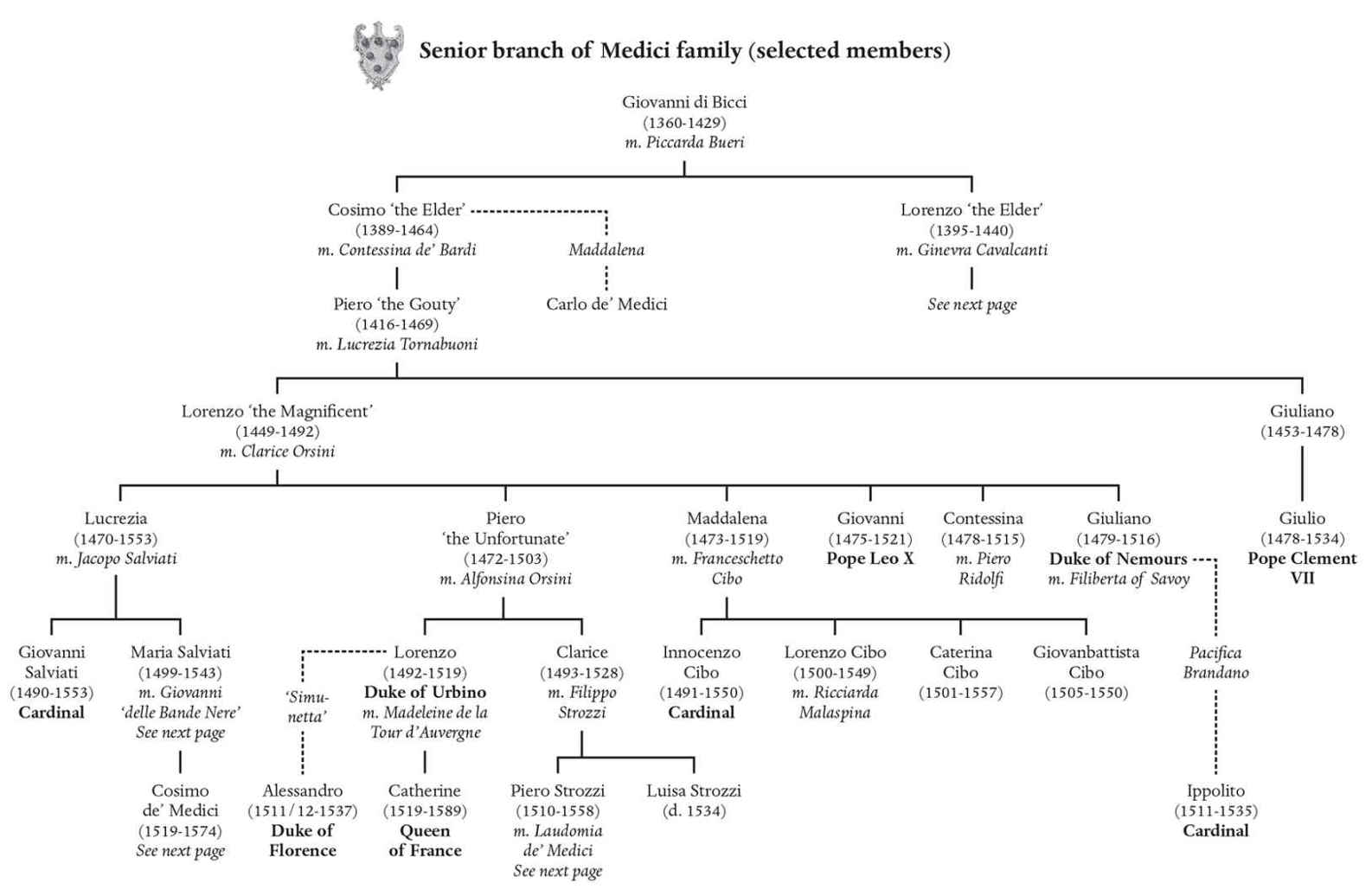

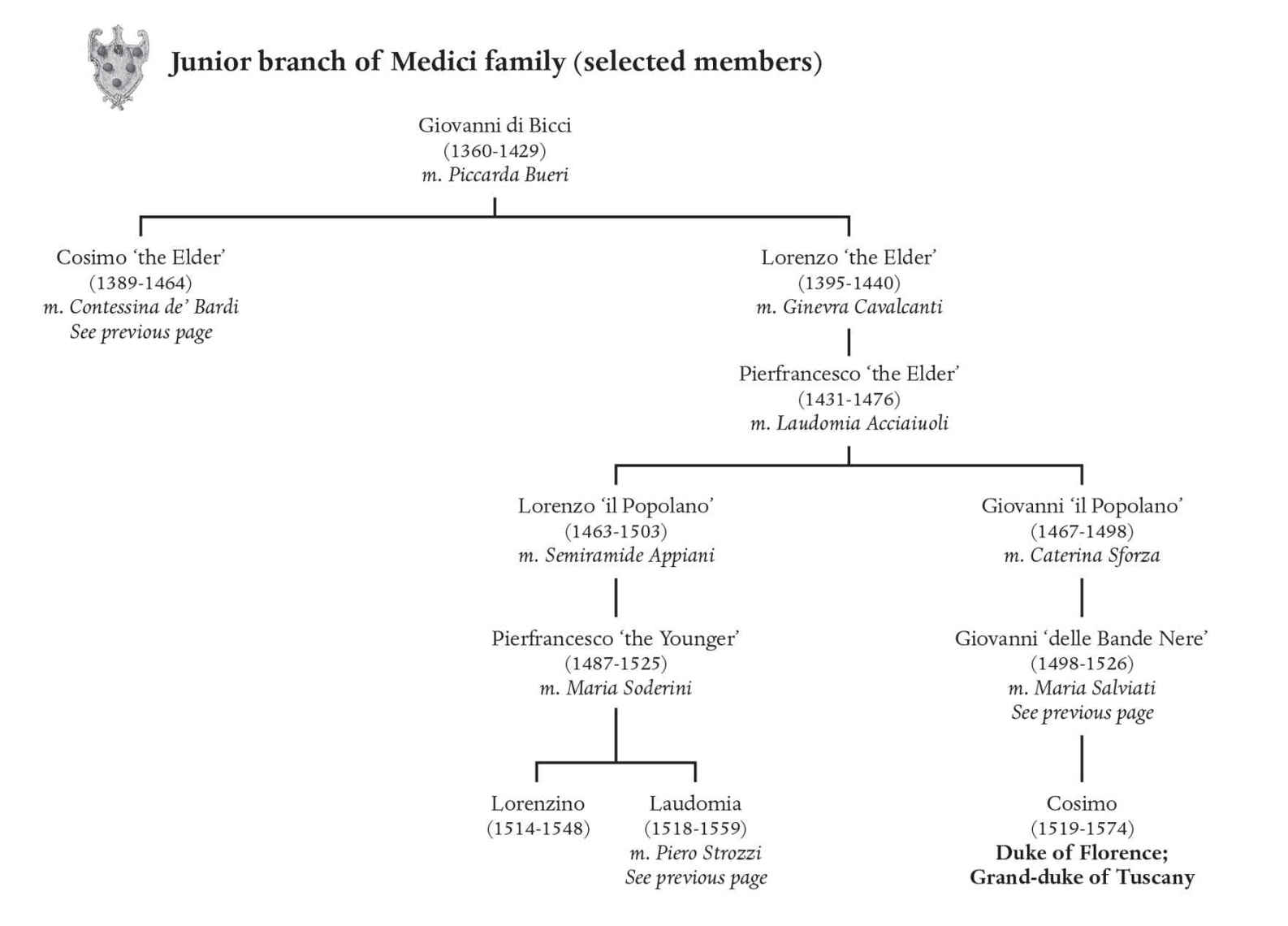

The year is 1531. After years of brutal war and political intrigue, the bastard son of a Medici duke and a half-negro maidservant rides into Florence. Within a year, he rules the city as its Prince.

Backed by the Pope and his future father-in-law, the Holy Roman Emperor, the ninteeen-year-old Alessandro faces down bloody family rivalry and the scheming hostility of Italys oligarchs to reassert the Medicis faltering grip on the turbulent city-state. Six years later, as he awaits an adulterous liaison, he will be murdered by his cousin in another mans bed.

From dazzling palaces and Tuscan villas to the treacherous backstreets of Florence and the corridors of papal power, the story of Alessandros spectacular rise, magnificient reign and violent demise takes us deep beneath the surface of power in Renaissance Italy a glamorous but deadly realm of spies, betrayal and and vendetta, illicit sex and fabulous displays of wealth, where the colour of ones skin meant little, but the strength of ones allegiances meant everything.

Rich with character and drama, The Black Prince of Florence is the first retelling of Alessandros life in two hundred years, shining a brilliant new light on this opulent, cut-throat world.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Catherine Fletcher is a historian of Renaissance and early modern Europe. Her first book, The Divorce of Henry VIII, brought to life the world of the Papal court at the time of the Tudors. Subsequently, Catherine worked with the set team on the BBCs adaptation of Wolf Hall, advising the production on the historical detail of religious ceremony, dress and furnishings. She broadcasts frequently for BBC Radio 4 on Italian Renaissance history and is currently a BBC New Generation Thinker. Catherine now holds the position of Associate Professor in History and Heritage at Swansea University, has previously held fellowships at the British School at Rome and the European University Institute, and has taught at Royal Holloway, Durham and Sheffield universities.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Divorce of Henry VIII: The Untold Story

TIMELINE

| 1511/12 | Alessandro born |

| 1513 | Giovanni de Medici elected Pope Leo X |

| 1519 | Birth of Alessandros half-sister, Catherine de Medici |

| 1519 | Death of Alessandros father, Lorenzo, duke of Urbino |

| 1521 | Death of Pope Leo X; succeeded by Adrian VI |

| 1522 | Alessandro made duke of Penne |

| 1522 | Birth of Margaret of Austria, illegitimate daughter of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V |

| 1523 | Death of Adrian VI; Giulio de Medici elected Pope Clement VII |

| 1524 | Alessandros cousin Ippolito made family figurehead in Florence |

| 1525 | Alessandro and Catherine sent to Florence; Alessandro lives at Poggio a Caiano villa, just outside city |

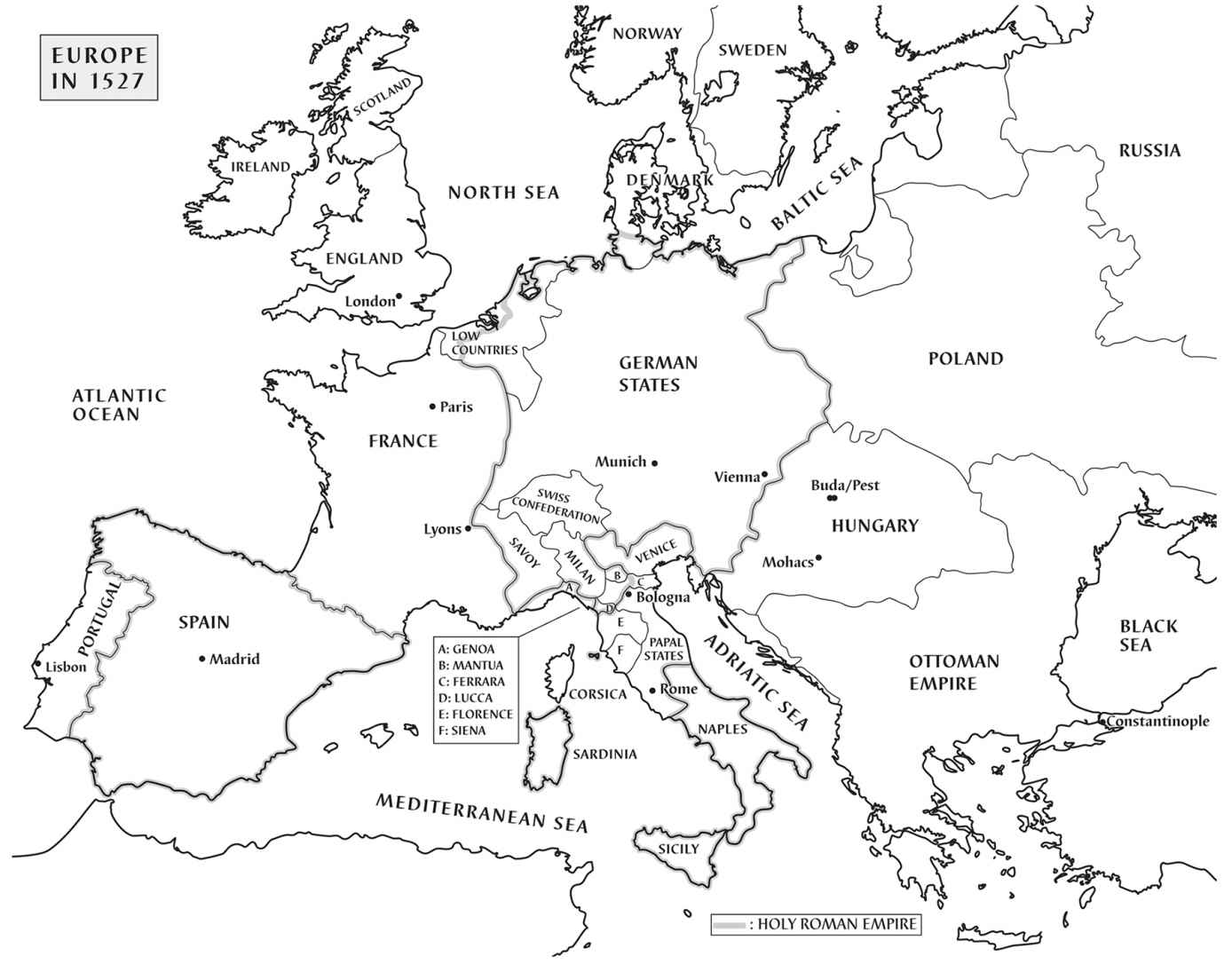

| 1527 | Sack of Rome; Medici family expelled from Florence and city government taken over by rivals |

| 1529 | January | Ippolito de Medici made a cardinal |

| June | Treaty of Barcelona between Clement VII and Charles V; Alessandro betrothed to Margaret of Austria |

| 1530 | February | Coronation of Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor in Bologna |

| August | Florentine regime falls after months of siege; pro-Medici faction takes over with Imperial backing |

| 1531 | OctoberMay | Alessandro travels around German states and Low Countries with court of Charles V |

| 1531 | July | Alessandro makes entry to Florence |

| 1532 | April | Ducal authority granted to Alessandro in constitutional reform of Florence |

| 1533 | April | Margaret of Austria visits Florence before going on to Naples |

| 1534 | July | Foundation stone of Fortezza da Basso laid |

| September | Death of Clement VII |

| 1535 | March | Delegation of Florentine exiles, Alessandros opponents, meets Charles in Barcelona |

| June | Ippolito de Medici implicated in plot to assassinate Alessandro |

| August | Ippolito de Medici poisoned |

| December | First garrison installed in Fortezza da Basso |

| 1536 | January | In Naples, Charles V hears cases of Alessandro and the exiled republicans on the government of Florence |

| February | Ring ceremony of Alessandro and Margaret |

| June | Marriage of Alessandro and Margaret |

| 1537 | January | Alessandro assassinated by cousin Lorenzino |

To my father

A NOTE ON MONEY

A range of coins and currencies circulated in Italy in the sixteenth century. The various city-states on the peninsula issued their own coinage, and exchange rates were not stable, particularly not during periods of war. Most day-to-day transactions were made in silver coins, known in Florence as grossi (groats); these were later replaced by the giulio. Major (and international) payments were denominated in gold coins such as ducats (the generic term for money of this type) and florins (the Florentine version). These were gradually superseded by the scudo, worth about 6 per cent less. A parallel system of lire, soldi and denari (pounds, shillings and pence) was often used for accounting purposes, though lire and soldi did not exist as coins. In the period covered by this book, a florin was worth somewhere between seven and eight lire.

Many people were not paid in cash alone, and reliable price indexes are lacking, so it is hard to estimate the purchasing power of particular sums of money. However, as a rough guide, unskilled labourers could expect to earn 2022 scudi in a year; skilled workers might make twice that. In 15045, Michelangelo had a stipend of 120 florins. Soldiers pay ranged from around thirty ducats a year to over 100 if they had to cover the cost of a horse and followers. Cardinals annual incomes, on the other hand, ranged in 1521 from 2,000 to 50,000 gold ducats. In 1528, it was estimated that around eighty Florentines had estates worth more than 50,000 florins: Jacopo Salviati, whose estate in Rome was valued at 350,000 florins in 1532, was one of the super-rich. Grain, a staple commodity, was considered expensive when in the 1530s the price of 200 kg reached five ducats, which gives some indication of how extraordinary the incomes of the wealthy were.

PROLOGUE

It was the eve of Epiphany, 1537, a night of the most dazzling moonlight. Alessandro de Medici, duke of Florence, had an assignation. His cousin Lorenzino, little Lorenzo, had promised him the favours of Caterina de Ginori.

Next page