The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

to

Marji Campi

and

Anthony Vivis

My guide and I came on that hidden road

to make our way back into the bright world;

and with no care for any rest, we climbed

he first, I following until I saw,

through a round opening, some of those things

of beauty heaven bears. It was from there

that we emerged, to see once more the stars.

Dante, The Divine Comedy, Inferno; Canto XXXIV

The marble not yet carved can hold the form

Of every thought the greatest artist has,

And no conception ever comes to pass

Unless the hand obeys the intellect.

Michelangelo, Sonnet (opening quatrain)

Foreword

Many people and organisations have helped me with this book. I have to thank the staffs of the Archive of Florence Cathedral, of the British Library, the Buonarroti House and the London Library. I should also like to thank Marji Campi for providing moral support, and for her patient reading and welcome constructive criticism of the manuscript; Heather Holden-Brown, editor and friend, for helping me develop the original idea; Jo Roberts-Miller; Sarah Ahmed; Anthony Vivis for his unfailing friendship, and Sophia Wickham for helping me with certain unsolved questions regarding the Medici. I must also thank all those Michelangelo scholars whose work has informed this effort.

I have tried to cover every possible established fact in an area where there is still much, sometimes enormous, disagreement about dates, names and events. Even the earliest chroniclers, Michelangelos contemporaries and first biographers Ascanio Condivi and Giorgio Vasari, are often far from accurate. I have been obliged to make certain choices with which some academics may disagree; but I have done so in good faith. In other words, I have done my best to check my facts. This is not a book, however, for those already in the know. It is designed to give people who do not already know it a taste of a world in which great creativity lived alongside political realism.

All dates conform to the modern Christian calendar.

A select bibliography at the end gives indications of sources, and pointers for further reading. Included in it are the publications from which the translated verses of Dante, Lorenzo de Medici and Michelangelos sonnets have been taken.

List of Illustrations

Prelude

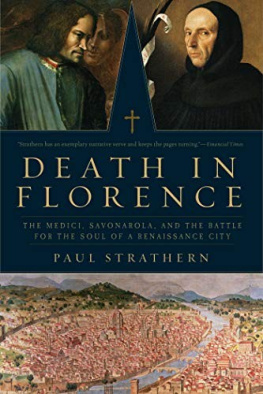

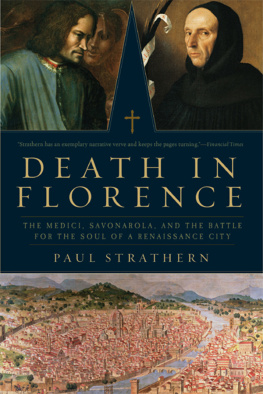

The subtitle of this book indicates that it covers twelve years in Florence, between the death of Lorenzo de Medici in April 1492 and the placing of Michelangelos early masterpiece of sculpture, his David, in the Piazza della Signoria in summer, 1504. But history doesnt stop and start at arbitrary dates, so this book will go back earlier than 1492 and go forward a little later than 1504 though the latter date is a good one to end on, since it more or less coincides with Michelangelos departure from Florence for Rome, where his genius would climb to ever greater heights. Here we are concerned with the flower in bud, not with the flower in bloom: but the former is seldom less exciting than the latter.

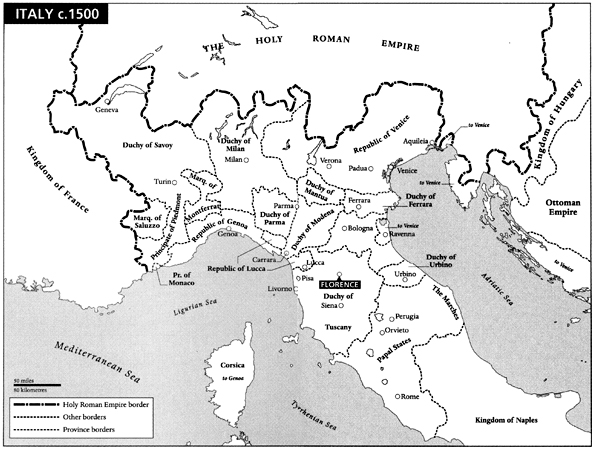

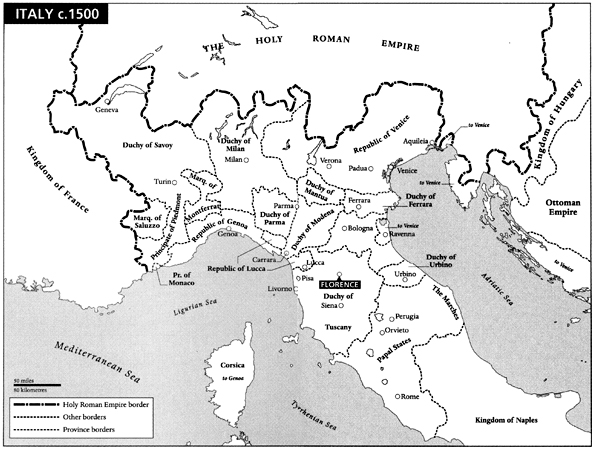

The theme here is not only focused on an artist of genius a man who from his early teens displayed a talent which outstripped his peers and has continued (with honorable exceptions) to outstrip their successors for five hundred years. The intertwined stories in this book are of a man and a city or rather, of two cities, because there is a space of several years within the chosen period when Michelangelo was absent from his native Florence, working in Rome. Family ties and political and religious preoccupations, however, kept him close to home emotionally, so that for the time between approximately 1494 and 1501 the aim has been to follow the separate, though connected, fortunes of Rome and Florence, and the artist who was to become in later life the honorary son of the former, but would in his heart always remain the true son of the latter not least because these were not simply separate towns within a country, but in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries the capitals of distinct and rival states, whose very usage and pronunciation of Italian differed.

One of the main reasons for reaching farther back in time than 1492 is Lorenzo de Medici. The year of his death may have been 1492 (Michelangelo had just turned seventeen), but this great citizen of Florence, who was Michelangelos first major patron, deserves a place near the centre of the stage. His short life and the political and social changes it witnessed are a vital ingredient of the scene-setting for the years which succeeded his early and agonising demise. This astute politician, connoisseur, sportsman and ineffective banker was one of the great diamonds in the crown of the early Renaissance. His role, even as a ghost hovering over the action, cannot be ignored in the short, intense story that follows.

Lorenzo the Magnificent (144992) towards the end of his life (engraving after Vasari)

The reason for choosing these twelve years is simple: they were among the most dramatic in the history of Florence, and they were the most dramatic of Michelangelos life the brief years during which he grew from an apprentice of thirteen to a master of twenty-five. After the David, he would develop into an artist of awesome maturity, but there would never quite be that rush of blood again, that acceleration of talent which those twelve years witnessed. His contemporaries in Florence at the time included some of the greatest luminaries of the age: Ghirlandaio the master of frescoes; the painters Dom Bartolommeo, Piero di Cosimo and Sandro Botticelli; the philosophers and Neoplatonists Angelo Poliziano, Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola; and Girolamo Savonarola, the overweening but influential critic of the decadent Borgia Papacy. An influential member of the citys administration was Niccol Machiavelli; and, a hugely valued and influential presence following his return to Florence in 1500 after an absence in Milan of nearly twenty years, was the great universal genius, Leonardo da Vinci, handsome, tall, dandified and worldly, whose rivalry with the much younger, short, unkempt, ugly and religious Michelangelo would place a strain on the short period that they knew each other during the early 1500s.

Florence, with its long history of republican government and uninterrupted prosperity (principally based on textiles and banking), had never forgotten the classical past of Italy. For a time, during the period of the Great Schism, between 1378 and 1417, when two rival popes each claimed to be sole head of the Church, and Rome was in abeyance, Florence was the principal city of Italy; and it had been a cradle of genius for at least a century before Michelangelos birth in 1475. Its eminent children could be traced back to the thirteenth century to the great, arrogant religious painter Cimabue, and after him Giotto and Dante, exact contemporaries, and their younger associate, the storyteller Giovanni Boccaccio, whose Decameron provided the principal inspiration for Geoffrey Chaucers Canterbury Tales, one of the first long narrative poems in English.