Conoscersi il miglior modo per capirsi

capirsi il solo modo per amarsi

(To know each other is the best way to

understand each otherto understand each

other is the only way to love each other.)

This wise and ancient maxim spoke directly to my heart as soon as I began to read this most fascinating book by Rabbi Benjamin Blech and Roy Doliner.

This adage is a valuable observation not only for relationships between human beings; it speaks perhaps even more profoundly with reference to interactions between religions as well as to dealings among nations.

In order to truly know each other, it is indispensable to know how to listen to each other, and above all to want to listen to each other.

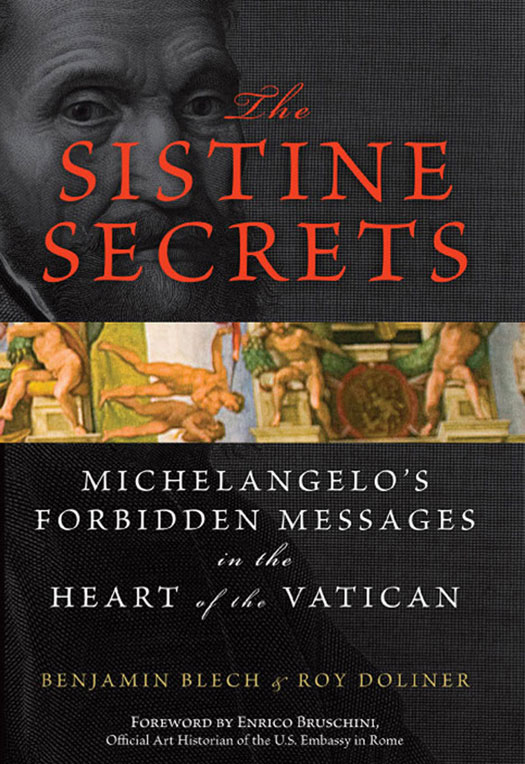

It seems to me that one of the important achievements of this groundbreaking book, among many others, is that it powerfully and clearly fulfills this mission. It pierces through the veil of countless puzzlements and hypotheses that, along with indisputable admiration, have always accompanied any visit to the Sistine Chapel. By filling in blanks resulting from a lack of understanding of teachings foreign to Christianitybut well known to Michelangelothe Sistine Chapel can now speak to us in a way it has never been understood before.

We have always known that Pope Sixtus IV wanted the Sistine Chapel to have the same dimensions as the Temple of Solomon, just as they were recorded by the prophet Samuel in the Bible in the book of Kings I (6:2). In the past, art and religion experts explained that this was purposely done to demonstrate that there is no contradiction between the Old and New Testaments, between the Bible and the Gospels, between the Jewish and the Christian religions.

Only now, through reading this remarkable book, have I learnedwith wonder, as an art historian, and with a certain embarrassment and sorrow as a Catholicthat this construction was considered a religious offense by the Jews. The Talmud, the collection and explication of the rabbinic traditions, clearly legislated that no one could build a functioning copy of the Holy Temple of Solomon in any location other than the holy Temple Mount in Jerusalem.

It is well to remember that this took place six centuries ago. In more recent times, many outdated insensitivities have thankfully been replaced with understanding and mutual respect. In this light, Pope John Paul II visited the Great Synagogue of Rome on April 13, 1986, and during that historic event the pontiff turned to the Jewish people, calling them for the first time, with respect and love, our elder brothers and sisters!

In January 2005, this very same great pontiff, feeling himself nearing the end of his earthly existence, made a gesture as historic as it was unique. He invited to the Vatican one hundred and sixty rabbis and cantors from all over the world. Organizing the encounter was Pave the Way Foundation, an international, interreligious association born out of the idea of creating and reinforcing bridges between the Jewish world and the Christian world. The purpose of the meeting was for the pope to receive a final blessing from the representatives of our elder brothers and sisters, while at the same time further strengthening the humanitarian ties between the two faiths.

This historic encounter turned out to be the very last audience of Pope Wojtila with any group. Three Jewish religious leaders had the privilege of being the first and only rabbis in the world to give a blessing to a pope in the name of the Jewish people. One of them was Benjamin Blech, coauthor of this volume, a professor of Talmud at Yeshiva University, an internationally noted teacher, lecturer, spiritual leader, and author of numerous books on spirituality read by people of all faiths.

I had the pleasure to personally meet the other author of this book, Roy Doliner, the day of the world premiere of the film The Nativity Story. It was the first time the Vatican had officially granted the use of the majestic Hall of Audiences for an artistic-cultural event.

Because of his profound knowledge of Jewish doctrine and history, and as a noted proponent of Talmudic study, Roy had been selected by the films producers and its director, Catherine Hardwick, as the official Judaicreligioushistorical consultant. For the historical consultant dealing with Rome and the life of Herod the Great, they had chosen yours truly. Through the production of The Nativity, Roy and I became friends.

That is how on several occasions Roy and I have been able to visit the Sistine Chapel in a very special wayafter closing hoursand each visit has been a chance to see the masterpiece of Michelangelo in a new and different way.

For these reasons, when I was asked to present this book, I accepted with pleasure. Having now read this work I find myself awed not only by the great scholarship of the authors, but also by the enormous and extremely interesting amount of new historic, artistic, and religious ideas contained within.

I had always wondered why, every time I entered the Sistine Chapel, not even one figure from the New Testament appeared on that splendid ceiling. I have finally found the most convincing answers here in this book.

The authors lead us on a true journey of discovery of other meanings, of diverse ways of seeing and understanding that which had always been right in front of our eyes and that now seems completely different.

With their guidance, we come to realize that Michelangelo performed an immense and ingenious act of concealment within the Sistine Chapel in order to convey numerous messages, veiled but powerful, that preach reconciliationreconciliation between reason and faith, between the Jewish Bible and the New Testament, and between Christian and Jew. Incredibly, we discover how the artist felt the need to communicate these dangerous concepts under perilous conditions at great personal risk to himself.

How was Michelangelo able to accomplish this daring act? The authors reveal that at times, Michelangelo uses codes or symbolic allusions that are partially hidden; at times, signs that can only be picked up and understood by certain religious, political, or esoteric groups. Still other times, all one needs is a mind free from preconceptions and open to new suggestions or ideas in order to understand his messages. It is even more interesting to realize that these symbols and allusions were done without being recognized by his papal patron. They were audaciously conceived in order to alleviate the frustration of the artist who, unable to openly have his say, wanted somehow to declare his message.

The book leads us, almost by the hand, in a documented but captivating style, to decode the hidden symbols. It gave me great pleasure to join with them, albeit with a bit of perplexity at the outset. It is certainly not easy to have to take a second look at the reassuring certainties that have accompanied us through life; but we cannot close our eyes, our mind, or our heart to those who have seen, from a different perspective, that which we have always taken for granted. Even if I might not share all of the interesting, intriguing, and at times stupefying new ideas, I am certain that this book is truly a new way to view the Sistine Chapel. It will be appreciated and treasured by all those who are seriously interested in the great ideas of religion, art, and the history of civilization. It will cause heated debates to spread forth for years to come.