Published by TAJ Books International LLC 2014

5501 Kincross Lane

Charlotte, North Carolina, USA

28277

www.tajbooks.com

www.tajminibooks.com

Copyright 2014 TAJ Books International LLC

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publisher and copyright holders.

All notations of errors or omissions (author inquiries, permissions) concerning the content of this book should be addressed to .

ISBN 978-1-84406-260-7

Printed in China

1 2 3 4 5 18 17 16 15 14

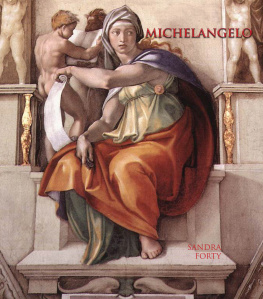

MICHELANGELO

14751564

M ichelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni is considered by many art experts to be the greatest Renaissance artist, surpassing even Leonardo da Vinci. Not only was he an exceptional sculptor but also a formidable painter, architect, and poet. His grandiose style completely complemented the expectations and opulent taste of his wealthy patrons, both secular and religious, who were eager to glorify themselves through grand artistic projects such as only Michelangelo could deliver.

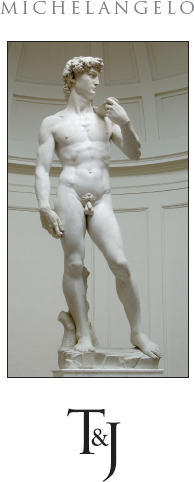

Michelangelos primary material was marble, and the most beautiful white stone in the world was mined from the Tuscan hills in Carrara. His magic was to turn this form of the purest limestone into living, breathing figures of exceptional beauty.

Michelangelo was obsessed with the perfect male physique and used the nude male figure in almost all of his sculptures and paintings. With unshakable religious faith, he believed that God shared his grace with humanity by giving them physical perfection and that it was his personal religious calling to reveal the spiritual significance of physical beauty through his work. Remarkably, Michelangelo also secured exceptional permission from the Catholic Church to study cadavers from which he learned about the musculature and skeletal human form in a way that even close observation of living men could not have taught him.

He was a complicated man, living his life in constant emotional turmoil and agony, misunderstood by virtually everyone around him. All his life he was moody and difficult, even surly and crude, openly struggling with his inner demons. Quick-tempered and confrontational, he would argue with his patrons and only got away with his outrageous behavior because of his outrageous talent.

Michelangelo was his own greatest critic, sensing his own imperfections: mental, spiritual, and physical. He was continually frustrated with his perceived inability to achieve the perfection in his work that he saw in his minds eye. Nevertheless, he worked at a feverish pace until a few days before he died.

Sadly, Michelangelo chronically lacked self-belief and self-confidence, and this tainted his relationships. He seems to have led a morally virtuous love life with a few select personal friends. He was genuinely fond of Urbino, his faithful servant of 24 years, and also became close to a number of his pupils, especially Giorgio Vasari and Ascanio Condivi, both of whom wrote biographies about him.

Michelangelo was genuinely inspired by Tommaso de Cavalieri, a young Roman nobleman with incomparable beauty, to whom he wrote poems and drawings. The only woman he is known to have admired was the widowed poetess Vittoria Colonna, whom he met in 1538, and with whom he had a spiritually passionate but platonic relationship for the 10 years he knew her before her death. He had a difficult relationship with his father and brothers, but he loved them and did all he could to support them. He once wrote, I will send you what you demand of me, even if I have to sell myself as a slave.

Portrait of Michelangelo by Marcello Venusti

Although Michelangelo had a photographic memory, he kept a collection of figure models that he referred to when looking for ideas. After deciding on his subject, he made an initial bozzetto (model) out of clay or wax, and then a more detailed terra-cotta maquette to show his client. After approval, the maquette was used to cast a wax model on which any changes and greater detail were incorporated.

The marble at Carrara was famed for its flawless white beauty and had been quarried since Roman times. During his lifetime Michelangelo must have visited the quarries well over 20 times. He would spend considerable time there, sometimes months, choosing exactly the right piece before getting it transported to his studio. When the stone eventually arrived, he painted the outline shape of the piece onto it and started blocking out the marble; unlike other sculptors, Michelangelo refused to allow anyone else to work on his pieces, even to do the blocking out. He then immersed his wax model in water and slowly lifted it out as he carved the marble. Referring to his sketches and models he free-carved the statue starting with the torso, using claw chisels in cross-hatching movements.

The results speak for themselves: Can anything compare to his statue of David or the Piet he carved at the age of 24?

Michelangelo Buonarroti was bom on March 6, 1475, in the small village of Caprese, in the Republic of Florence, at a time when a united Italy was not even a distant idea. He was bom into a respectable family of local fiscal merchants, and his father, Leonardo di Buonarrota Simoni, was at the time working as a podest (local magistrate or minor official). His mother, Francesca Neri, was his fathers second wife, and although frail she gave him five sons of which Michelangelo was the second. Within a few weeks of Michelangelos birth, his father moved the family to Florence where his mother fell ill. Michelangelo was sent to a wet nurse in a family of stonecutters. He later remarked, With my wet-nurses milk, I sucked in the hammer and chisels I use for my statues. His mother went on to have three more sons but died in 1481 when Michelangelo was six years old.

Michelangelo was clearly an intelligent little boy and his ambitious father saw in him the potential to become a businessman, so he sent him to the school of master linguist Francesco Galeota. But Latin studies and the like held little attraction and interest for Michelangelo who, despite being shy, was much more enthused by the painters and craftsmen working in the local churches. His sketches of them alerted his father to his true interests. His father was most discouraged. He wanted a respectable business career for his son, not a socially demeaning laboring job such as an artist, so that he could uphold the family standing in Florence. Father and son fell out and Michelangelo felt the hurt for the rest of his life. He was tormented by their estrangement, but was adamant that he would become an artist.

In 1487 his father remarried for the third time and fathered another four children. By then Michelangelos precocious artistic ability had convinced his father that his second son was not going to follow him into the family business. So at the age of 13 Michelangelo was sent to be an apprentice at the most fashionable painters workshop in Florence, the workshop of Domenico Ghirlandaio where he learned the art of fresco.

After only a year, Ghirlandaio was more or less commanded by the powerful and much- feared Lorenzo de Medici to send him his two best pupilshe recommended Michelangelo and Francesco Granaccito work in the Medici family sculpture workshops. The palace of Lorenzo de Medici was one of the leading cultural centers in Italy, and Michelangelo was offered the desirable opportunity to study anatomy and classical sculpture in the Medici palace gardens. He went there between 1489 and 1490. Lorenzo de Medici was immediately impressed and soon invited the young sculptor to live in his palace, to be a part of his court, and to be educated beside his own children.

Next page