Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

We hope you enjoyed reading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster.

ALSO BY MILES J. UNGER

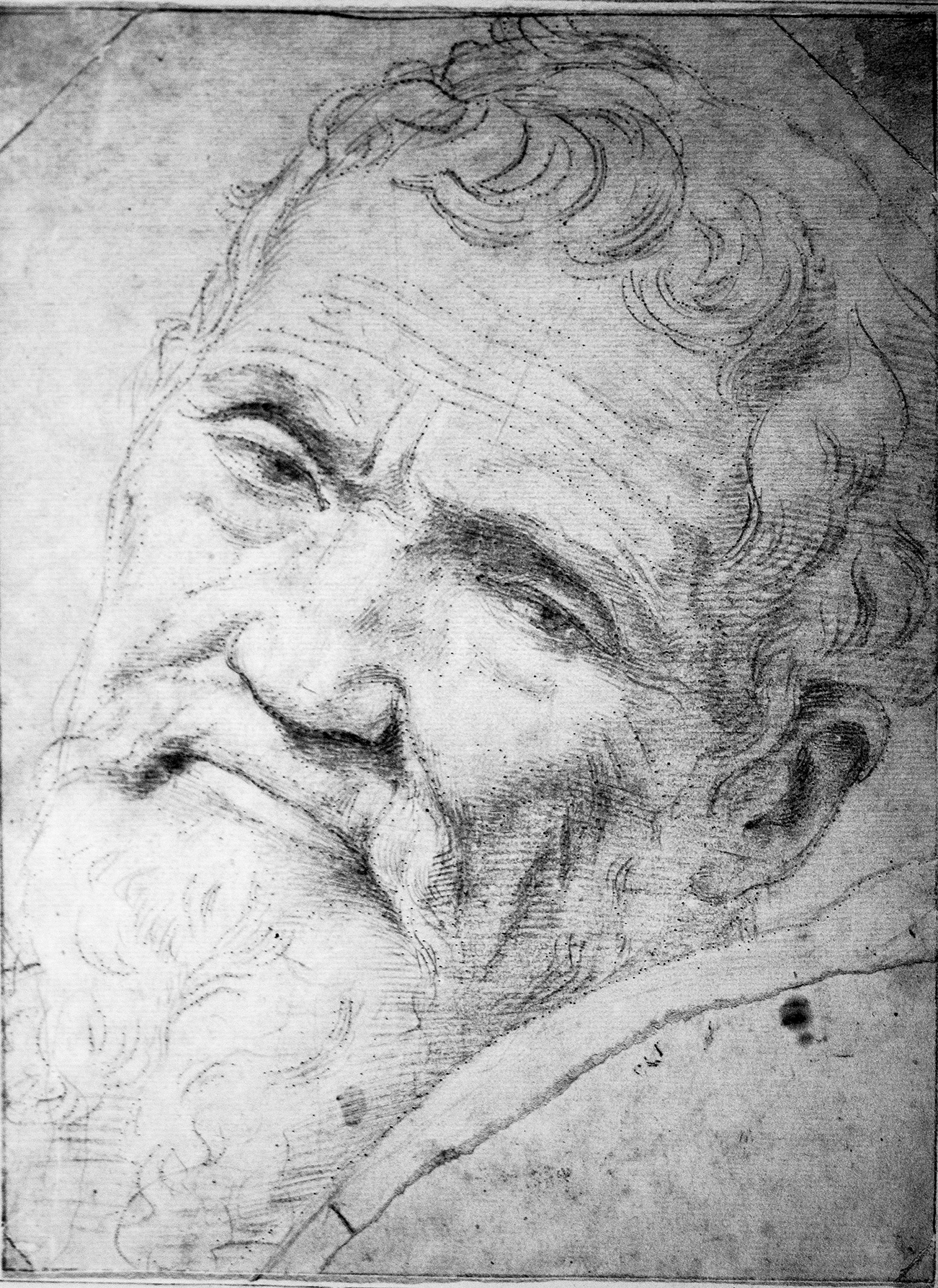

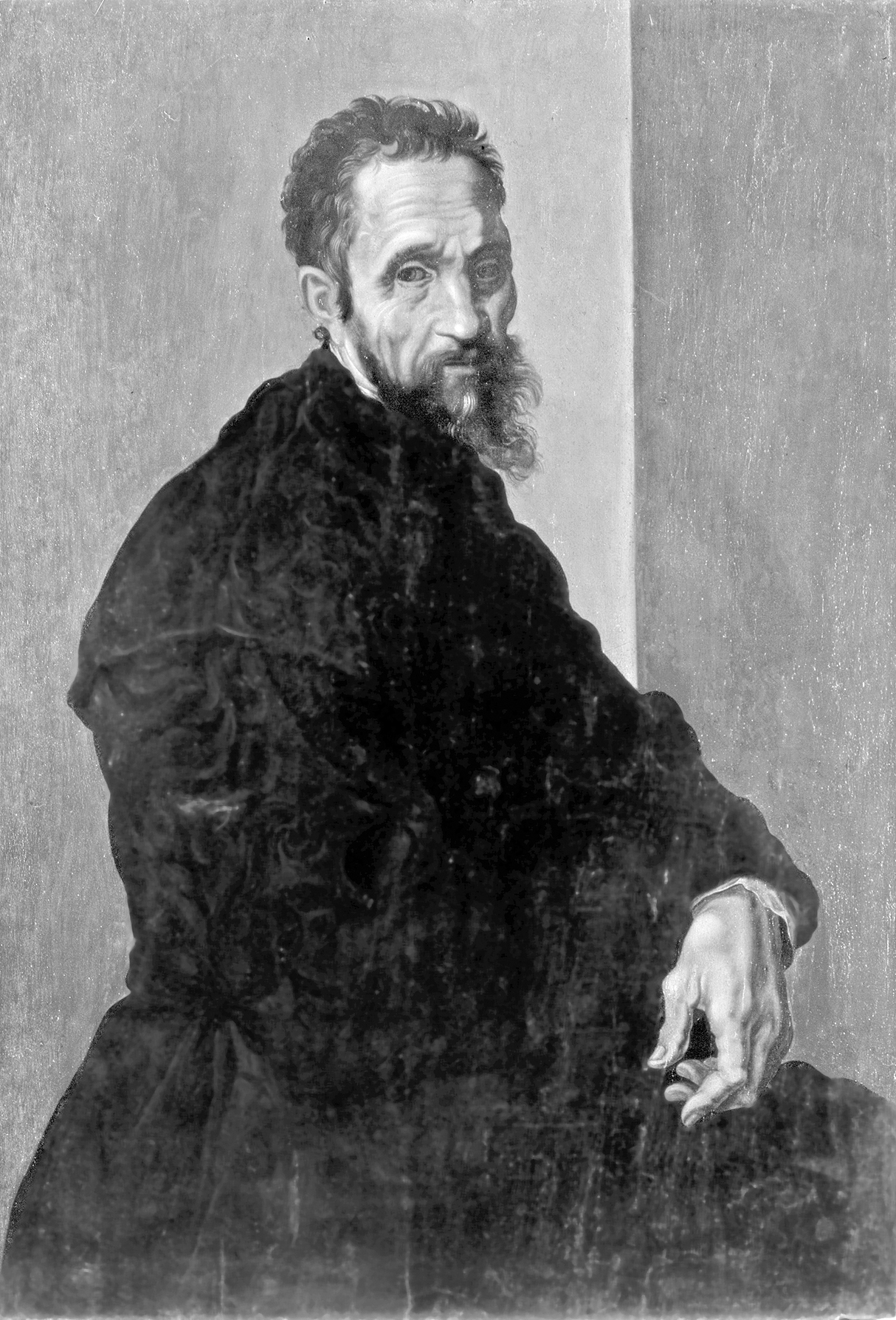

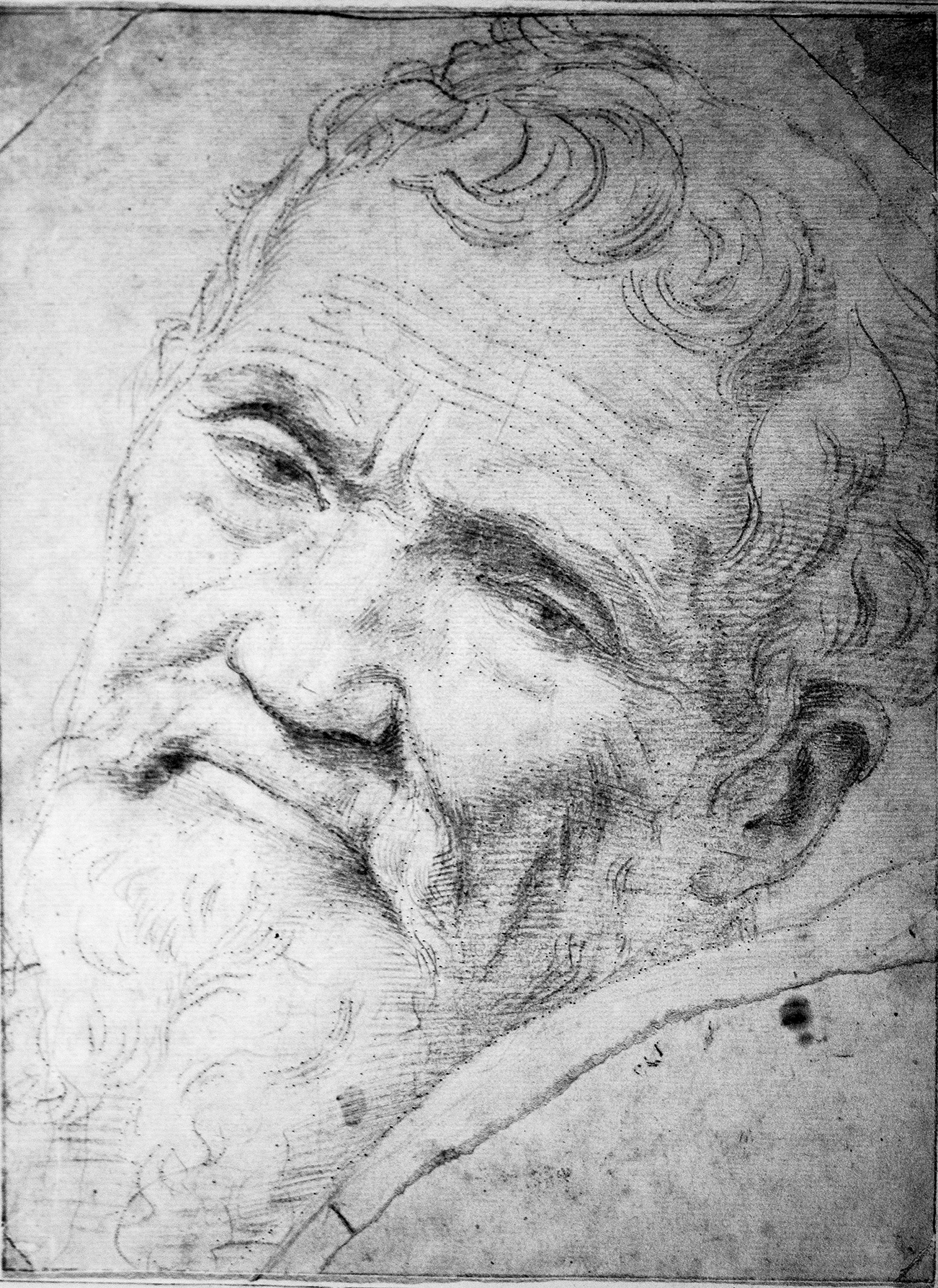

Daniele da Volterra, Portrait of Michelangelo.

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2014 by Miles Unger

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition July 2014

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Ruth Lee-Mui

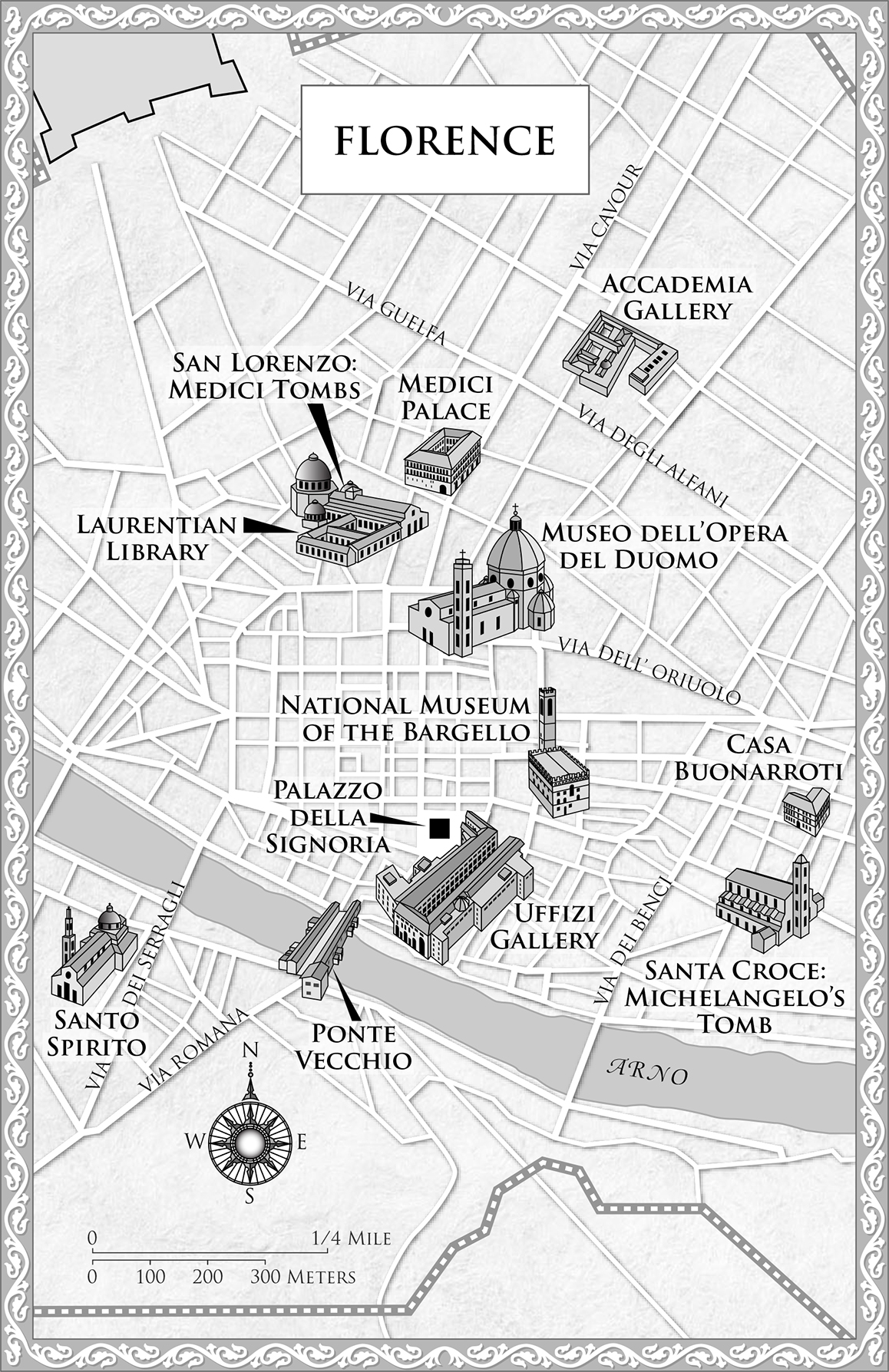

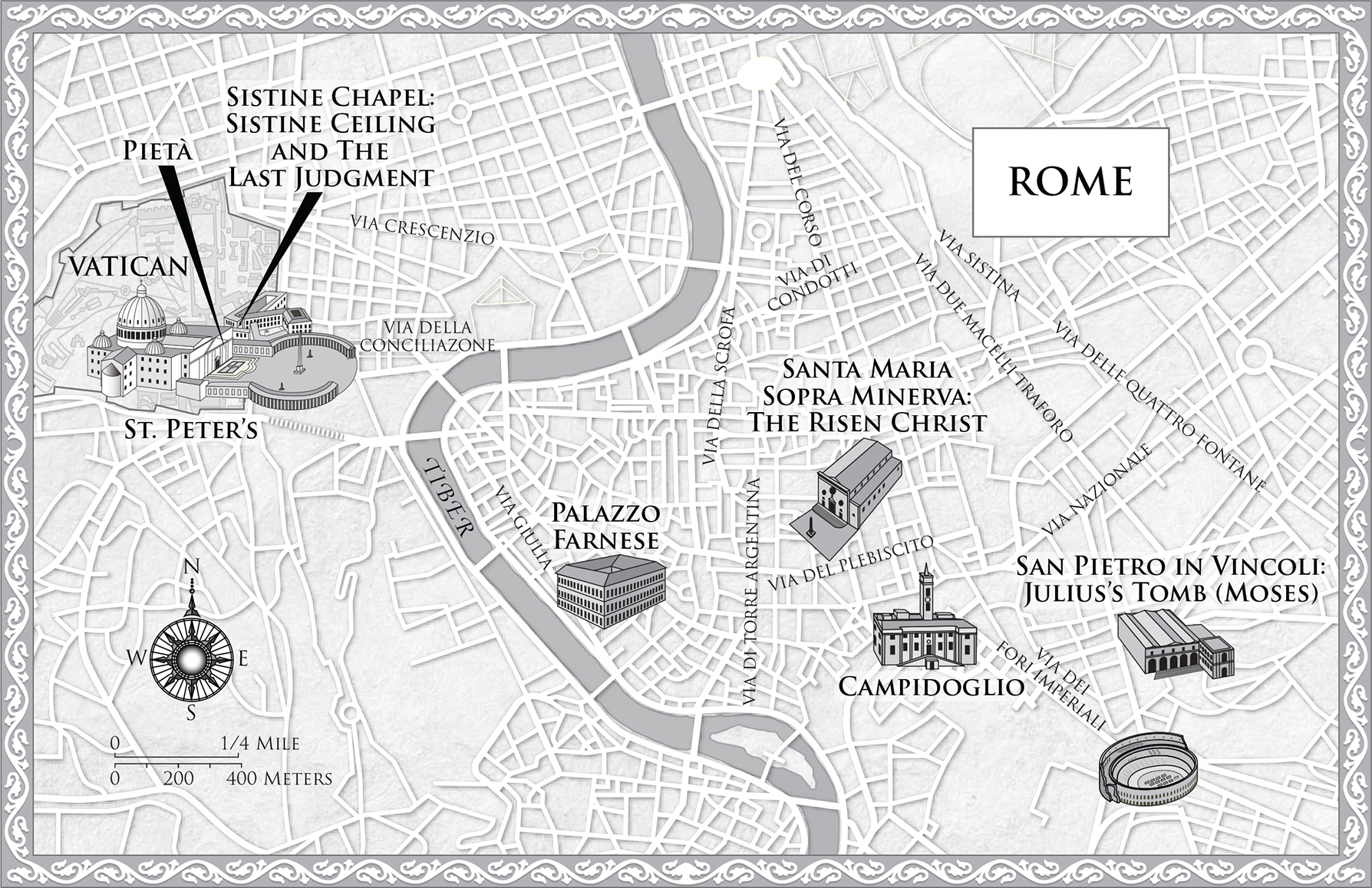

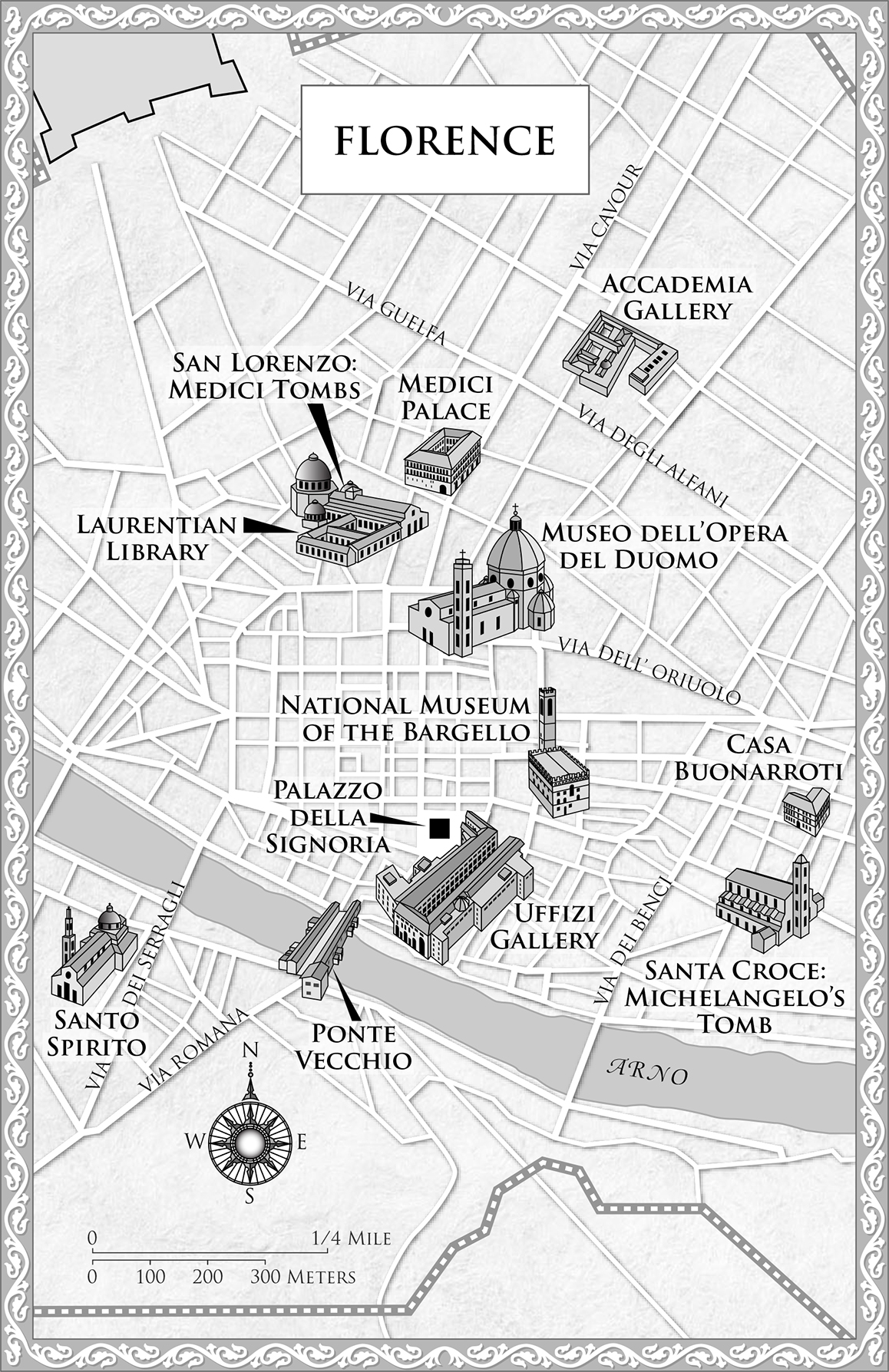

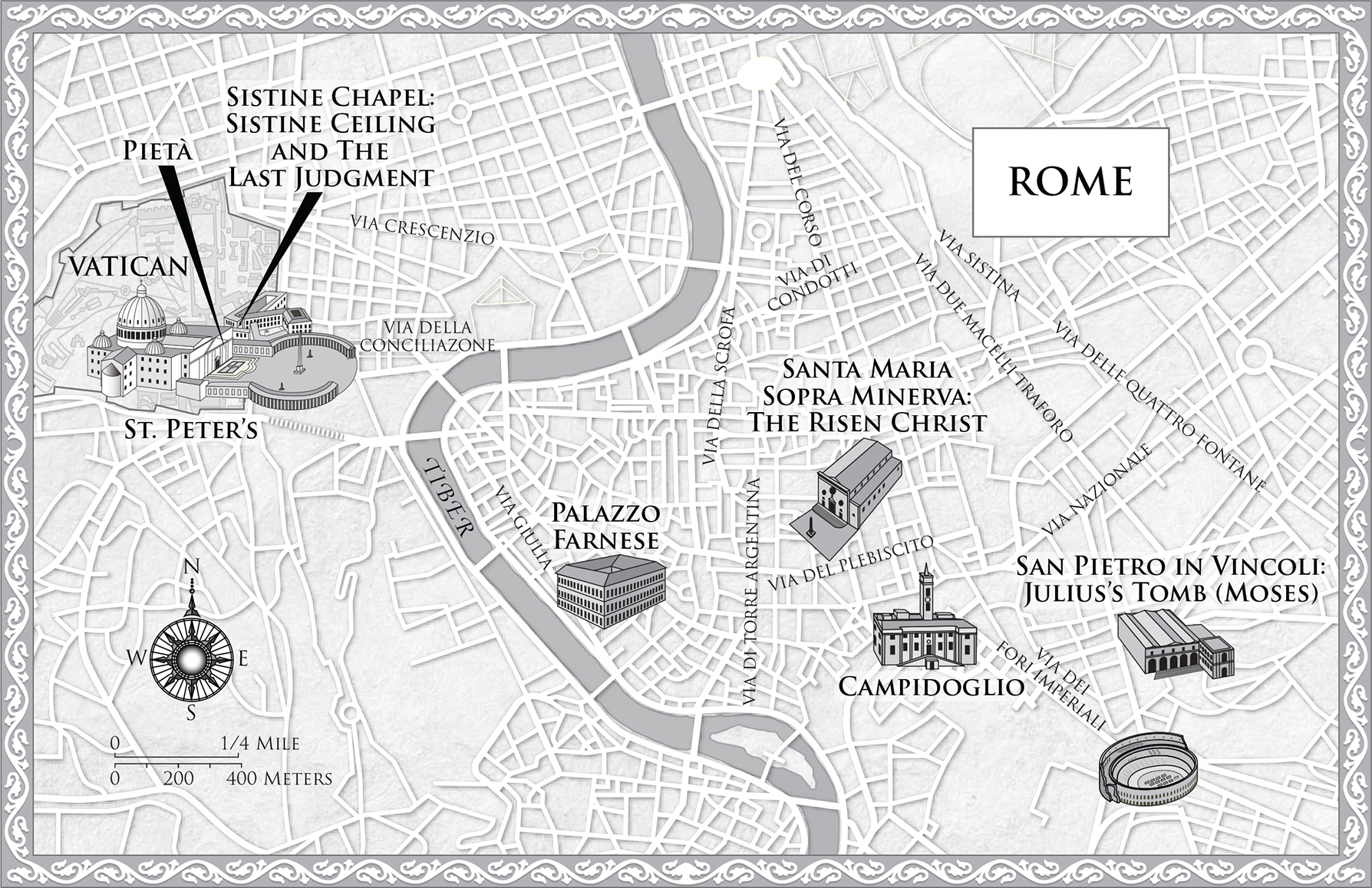

Maps by Paul J. Pugliese

Jacket design by Michael Accordino

Jacket art by Michelangelo Buonarroti Scala/Art Resource, NY; street sign Hedda Gjerpen/Getty Images

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Unger, Miles.

Michelangelo : a life in six masterpieces / Miles J. Unger.

pagescm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1.Michelangelo Buonarroti, 14751564.2.ArtistsItalyBiography.I.Title.

N6923.B9U542014

709.2dc23

[B]

2013045778

ISBN 978-1-4516-7874-1

ISBN 978-1-4516-7880-2 (ebook)

To Emily and Rachel, my pride and joy

Contents

MICHELANGELO:

THE MYTH AND THE MAN

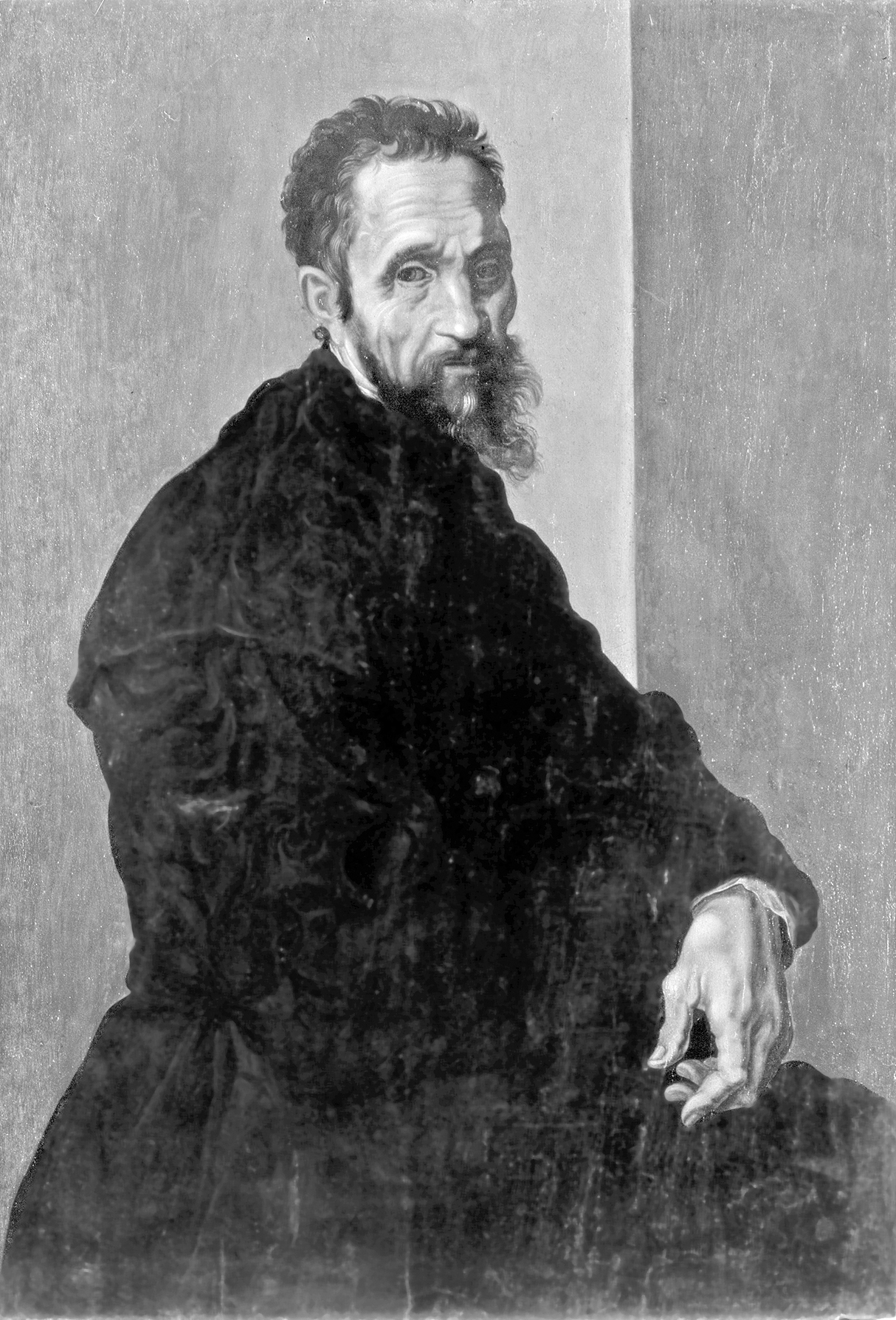

Portrait of Michelangelo Buonarroti by Jacopino del Conte Scala/Art Resource, NY

I

Michelangelo: The Myth and the Man

Michael, more than mortal man, angel divine...

Ariosto, Orlando Furioso

I. MICHAEL, MORE THAN MORTAL MAN, ANGEL DIVINE

In the spring of 1548, Michelangelo Buonarroti dashed off a brief note to his nephew Lionardo in Florence. As was often the case with the seventy-three-year-old artist, he felt aggrieved. Tell the priest not to write me any longer as Michelangelo sculptor, he wrote in a huff, because here [in Rome] Im known only as Michelangelo Buonarroti, and if a Florentine citizen wants to have an altarpiece painted, he must find himself a painter. I was never a painter or a sculptor like one who keeps a shop. I havent done so in order to uphold the honor of my father and brothers. While it is true that I have served three popes, that was only because I was forced to.

One reason for his annoyance was practical. As he suggests at the end of the letter where he enlists his nephew in a little deception... as to what Ive just written, dont say anything to the priest because I wish him to think that I never received your letterthere are other sculptors in Rome with similar names and any imprecision in the form of the address is likely to cause his mail to go astray. But the real explanation lies elsewhere. The priest has not only been careless: worse, he has misunderstood the nature of his calling. Michelangelo bristles at being mistaken for one of those daubers who hangs out a shingle advertising Madonnas and portraits to order and priced by the square foot. Nothing could be further from the truth, he tells Lionardo, as if he too needed to be reminded of the kind of man his uncle is. He is an artist, a visionary whose unique gift sets him apart from ordinary mortals.

In this petulant notewritten in haste by an old man whose crankiness was exacerbated by a recent attack of kidney stoneswe can sense the frustration that came from a lifetime spent battling those who viewed his profession with contempt. In the face of the skeptics and the scoffers, Michelangelo promoted a new conception of the artist, one in which the crass demands of commerce and the demeaning associations of manual labor have been sloughed off to reveal a creature as yet ill-defined but still thoroughly magnificent.

I was never a painter or a sculptor like one who keeps a shop, he insists. But if not, what kind of artist is he? Implicit in Michelangelos outburst is a radical claim: the painter or sculptor was no longer just a humble craftsman but a shaman or secular prophet, and the work of his hands was akin to holy writ.

Michelangelos letter to his nephew offers a telling insight into the artists state of mind, one thats all the more valuable for being private and unrehearsed. Precisely because theres so little at stake, and because the people involved were of no particular importance, we get the feeling we are peeking through the curtains and seeing the man as he really was when no one was looking, in his robe and slippers, his hair uncombed. The touchiness and fragile vanity Michelangelo displays are perhaps surprising, since by the time he wrote the letter he had already achieved a worldly success almost unparalleled for any artist in any age. [W]hat greater and clearer sign can we ever have of the excellence of this man than the contention of the Princes of the world for him? asked Ascanio Condivi, his friend and biographer. Courted by the greatest lords of Europe who begged for even a minor work from his hands, why bother to respond to a tactless Florentine nobody?

The truth is that the priest had touched him where he was most tender. Michelangelos peevish response is a farcical echo of those epic battles with popes and princes who were often just as blind to the nature of his achievement. In fact, Michelangelos entire life was a rebuke to those who thought the artists job was to supply pretty images to order for anyone with a few ducats in his pocket. Michelangelo insisted that the purpose of art, at least when practiced at the highest level, was to channel the most profound aspirations of the human spirit. These could not be summoned at will or purchased like melons in the market. By stubbornly, even pugnaciously, pursuing this ideal, Michelangelo transformed both the practice of art and our conception of the artists role in society.

Michelangelos long, illustrious career marks the point at which the artist definitively transcends his humble origins in the laboring class and takes his place alongside scholars and princes of the Church as an intellectual and spiritual leader. As Michelangelos fame spread, some of his patrons persisted in treating him as little more than a household servantalbeit of a particularly eccentric and disobedient sortbut many contemporaries acknowledged that he was a new kind of artist, indeed a new kind of man, a secular saint who was to be exalted but also feared. Even someone as powerful as Pope Leo X was daunted by the prospect of employing him, grumbling, [H]e is terrible, as you see. It is impossible to work with him. Leos cousin, Pope Clement VII, was more amused than outraged at his servants insubordination. When Buonarroti comes to see me, he said, laughing, I always take a seat and bid him to be seated, feeling that he will do so without leave.