Contents

Guide

Page List

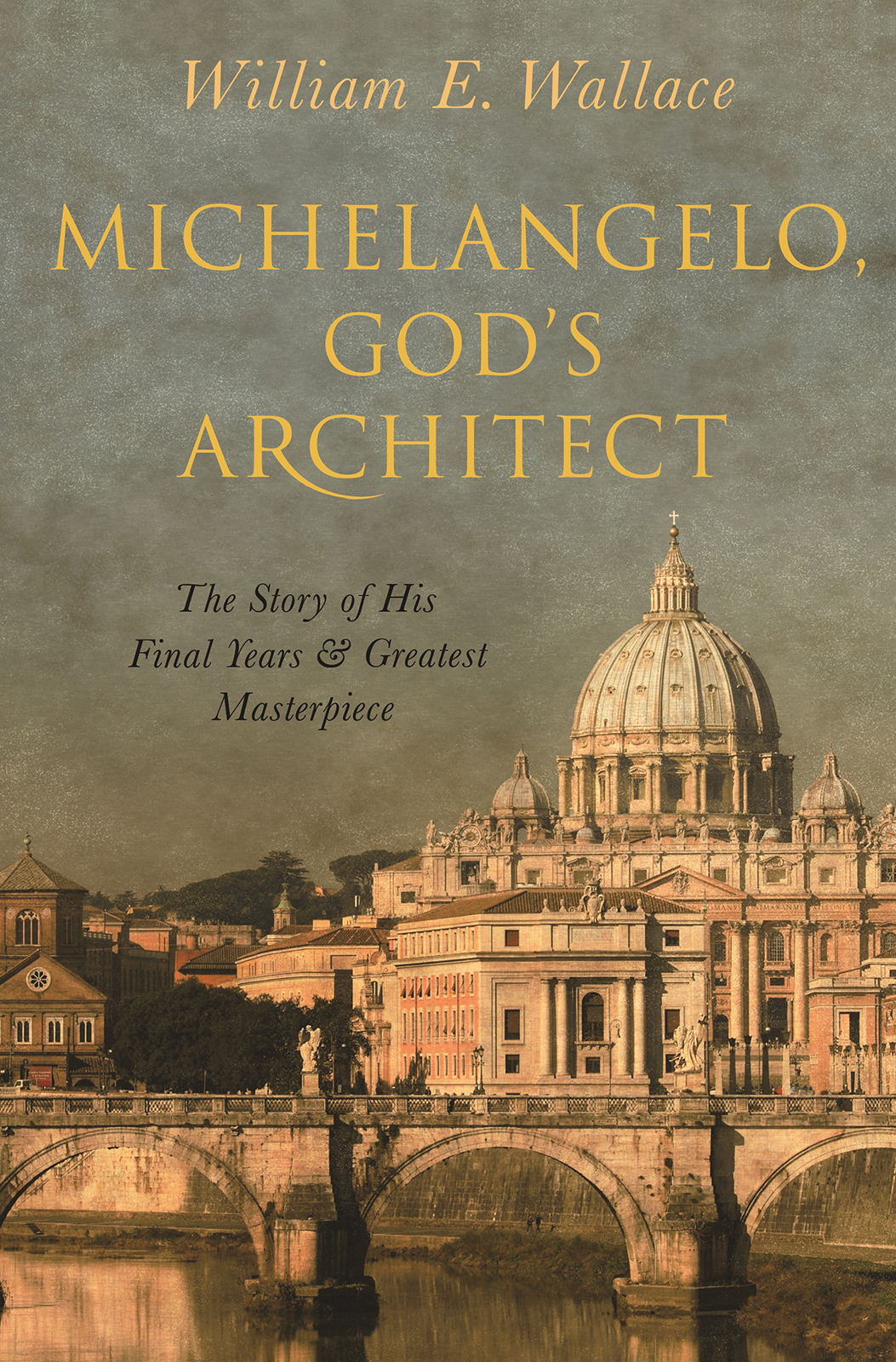

MICHELANGELO,

GODS ARCHITECT

MICHELANGELO,

GODS ARCHITECT

THE STORY OF HIS FINAL YEARS AND

GREATEST MASTERPIECE

WILLIAM E. WALLACE

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2019 by William E. Wallace

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work

should be sent to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Jacket illustrations: (front) Ponte SantAngelo and St. Peters Basilica, Vatican City; (spine) Jacopino del Conte, Portrait of Michelangelo, ca. 1540, oil on panel, 88 cm (34.6) 64 cm (25.1)

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-19549-0

eISBN 978-0-691-19439-4 (e-book)

Version 1.0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019941489

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Jacket and text design by Leslie Flis

To Paul Barolsky, who taught me the value of a good story

CONTENTS

ix

CHAPTER 1

MOSES 7

CHAPTER 2

FRIENDS AT SEVENTY MATTER MORE 28

CHAPTER 3

A LONG-LIVED POPE 56

CHAPTER 4

ARCHITECT OF ST. PETERS 75

CHAPTER 5

A NEW POPE: JULIUS III 112

CHAPTER 6

ROME 1555 154

CHAPTER 7

ARCHITECT OF ROME 184

CHAPTER 8

GODS ARCHITECT 215

PREFACE

Having written a biography of Michelangelo, I thought I was done with the artist. But, as Leonardo famously mused, Tell me if anything is ever done. And as my mentor Howard Hibbard once remarked, There is no such thing as a definitive book or a final word on great art or artists. Indeed, as I wrote the final pages of my biography, I became increasingly drawn to the poignant narrative of an aging artist confronting the greatest challenge of his creative life: to build New St. Peters all the while knowing he would never see it to completion.

I think I needed to pass age sixty before I could write a book about Michelangelo in old age, and that means that I have incurred many years of personal and scholarly debts. I would like to thank Nicholas Terpstra, Elizabeth Cropper, and the board members of the Renaissance Society of America for the invitation to deliver the Josephine Waters Bennett Lecture in 2014, which permitted me to sketch the broad ideas for the book and to publish them in Renaissance Quarterly. For the rare privilege of visiting the Pauline Chapel on multiple occasions, I am grateful to Antonio Paolucci, Arnold Nesselrath, and Marco Pratelli. I would like to thank Vitale Zanchettin for an afternoon spent in some normally inaccessible parts of St. Peters; to Richard Goldthwaite, Eve Borsook, Peggy Haines, and Joseph Connors for always asking the most penetrating questions; to Jim Saslow for many questions answered, especially about Michelangelos poetry; to Paul and Ruth Barolsky, Ralph Lieberman, Maria Ruvoldt, and Deborah Parker for years of conversation regarding everything Michelangelo and Michelangelesque; to Sarah McHam for first permitting me to write an essay employing a fictionalized voice; to Eric Denker and Meredith Gill, Livio Pestilli and Wendy Imperial, Jack Freiberg and Franco Di Fazio, Michael Rocke, Andrew McCormick, and Nelda Ferace for sharing Michelangelo in Italy and always eating well afterward, and to Judith Martin for my title. Four persons deserve special thanks: Roger Crum for his attentive labor on the entire manuscript, Eric Denker for being my longest-standing friendart historical and otherwise, Elizabeth Fagan for being my wife, companion, and invaluable editor of forty-five years, and Paul Barolsky, to whom I warmly dedicate this book.

Of particular value was the fall 2014 spent at Villa I Tatti as a visiting senior professor. I am especially grateful to the then director Lino Pertile and to Anna Bensted for extending to me their generous and supremely gracious hospitality. Thanks to them and a wonderful group of fellows that included Lucio Biasiori, Francesco Borghese, Dario Brancato, Gregorio Escobar, Cyril Gerbron, Jessica Goethals, Caitlin Henningsen, Joost Keizer, Rebecca Long, Francesco Lucioli, Lia Markey, Laura Moretti, Alessandro Polcri, Sean Roberts, Sarah Ross, Paola Ugolini, and Susan Weiss, I was stimulated to write large portions of the current manuscript. Needless to saybut it is well worth saying nonethelessmembers of the staff and the I Tatti family were equally instrumental in offering the ideal conditions in which to ruminate about growing olda luxury Michelangelo never enjoyed. My thanks are extended especially to Allen Grieco, Jonathan Nelson, and Michael Rocke.

Over the years I have been blessed with wonderful friends and colleagues and a few exceptional students who have done much to shape my views of Michelangelo. The following have all contributed in small or larger ways to the present book. My gratitude is not adequately expressed in the following impersonal alphabetical listing: James Anno, Simonetta Brandolini dAdda, Bernadine Barnes, Cammy Brothers, Caroline Bruzelius, Jill Carrington, Silvia Catitti, Joseph Connors, Bill Cook, Roy Eriksen, Emily Fenichel, Meredith Gill, Marcia Hall, Emily Hanson, Eric Hupe, Paul Joannides, Nathaniel Jones, Stephanie Kaplan, Ross King, Margaret Kuntz, Tom Martin, the late Jerry McAdams, Erin Sutherland Minter, Rene Mulcahy, Mike Orlofsky, John Paoletti, Deborah Parker, Gary Radke, Sheryl Reiss, Andrea Rizzi, Charles Robertson, Patricia Rubin, Carl Smith, Tammy Smithers, and last but not least (since I am sensitive to alphabetical discrimination), Shelley Zuraw. I would also like to extend thanks to Sarah Braver, Hannah Wier, Hua Zhao, and Betha Whitlow for their assistance with the books illustrations.

It is an honor and privilege to publish a book with a former student, now editor and colleague, Michelle Komie.

MICHELANGELO,

GODS ARCHITECT

INTRODUCTION

For a half year in Rome, I looked from my window on the dome of St. Peters, the dome that Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (14751564) designed but never actually saw. The fact that Michelangelo remained committed to building this crowning feature of St. Peters Basilica in Vatican City for seventeen years with no hope of finishing the task made writing this book seem simple by comparison.

In the fifteen years between writing a monograph, Michelangelo at San Lorenzo: The Genius as Entrepreneur (1994), and a biography, Michelangelo: The Artist, the Man, and His Times (2010), I became increasingly aware of how much the story of the artists heroic rise to fame had deflected attention from his very different but no less enterprising later life. Resisting the attraction of that well-rehearsed narrative, this book examines the final two decades of Michelangelos career, from the installation of the tomb of Pope Julius II in Romes San Pietro in Vincoli in 1545 to his death in 1564that is, from age seventy to a few weeks shy of his eighty-ninth birthday. Notably, while this period represents fully one-fifth of the artists long life and constitutes nearly a quarter of his approximately seventy-five-year artistic career, it remains the least familiar segment of the artists biography.