CONCLUSION

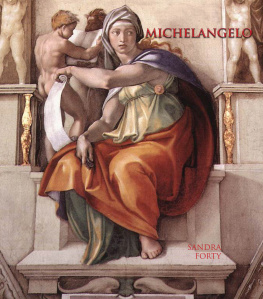

T he brooding presence of The Last Judgement on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel inevitably complicates the experience of looking at the ceiling above. The work casts a long shadow. It projects the penitential sense of spiritual mission that Michelangelo developed in later life on to the frescoes that he had painted while still a young man. Turning from The Last Judgement to the Sistine Chapel ceiling, the viewer is apt to pay greater attention to the more severe and apocalyptic elements of the earlier frescoes to find in scenes such as The Deluge , with its helpless throng of the doomed, or The Brazen Serpent , with its tumble of agonised bodies, vivid foreshadowings of Michelangelos later, darker, vision. The paintings of the Sistine Chapel ceiling certainly express a severe and deeply pious Christian conception of the pattern of universal history, and of mankinds place within it. But The Last Judgement is liable to make that conception, that vision, seem rather more bleak than it was originally intended to be.

The fact that Michelangelo himself reshaped the meanings of his own great fresco cycle in later life raises larger questions of interpretation. How do the ceilings many images relate to one another? In what order or hierarchy should they be viewed? What is the nature of the plan according to which those images are arranged, and what exactly is the vision that underlies it? Was the plan Michelangelos own, or was he painting to a theological programme devised by others? If he did receive instructions, to what extent did he follow them, and to what extent did he exercise creative licence? These issues are fiercely debated in the existing literature about the Sistine ceiling.

No documentary evidence has been found to settle such questions. But it seems improbable that Michelangelo was allowed total freedom in his choice of scenes and subjects for such an important commission. It is likely that he discussed his ideas, that he sought advice and that he needed approval of some kind before going ahead with the actual painting. But a number of scholars go considerably further than that modest set of assumptions. They argue that Michelangelo must have worked to a specific and theologically demanding programme a document, perhaps augmented by a diagram, which not only dictated the subject matter of every one of the images on the ceiling, but also composed them into a pattern of cross-references and allusions designed to convey a particular set of complex and arcane theological propositions.

Such scholars have gone to great lengths to reconstruct that hypothetical document, to identify its author and explain the ways in which his theology shaped Michelangelos frescoes. The leading theologian of Julius IIs pontificate, Giles of Viterbo, has often been proposed as the author of such a text. One author has suggested that Giles wrote a complex programme based on the venerable theology of St Augustines City of God , and that concealed within Michelangelos frescoes there lies an allegory of Augustines two cities, the earthly and the heavenly. A forcefully argued counter-suggestion also has Giles as the author of the programme, but asserts that his source of inspiration lay not in St Augustine but in the writings of a twelfth-century Franciscan mystic named Joachim of Fiore, whose writings were the focus of renewed interest in early sixteenth-century Rome. Other candidates proposed for the authorship of a programme for the ceiling include another papal theologian by the name of Marco Vigerio, as well as Cardinal Alidosi with whom Michelangelo agreed the contract to paint the ceiling and a disciple of Savonarolas by the name of Sante Pagnini. Each solution is different, but all are inspired by the same dream, that of finding a single code or key to unlock the totality of meaning embodied in the pictures.

Theologically totalitarian interpretations of the ceiling all have major flaws. This is not only because they are marred by numerous demonstrable failures of fit with the actual paintings of the chapel (as critics of each hypothesis have been swift to point out). It is because they all represent what in philosophy might be termed a category mistake a fundamental error about the very nature of that which they seek to describe. There is little point in debating the respective merits of different attempts to find a key to the Sistine ceiling, precisely because it is the very idea of a complete explanation, in the form of an underlying text that might magically explain all, that is itself at fault. There is no good reason to suppose that Michelangelo was ever required to paint in accordance with an all-encompassing programme. It was not common practice to devise such programmes. No such text has been found for the Sistine Chapel ceiling, despite years of archival research undertaken in the hope of finding such a thing. In fact no equivalent document, nor any reference to one, has been found for any major fresco cycle, painted anywhere in Italy, at any time during the Renaissance. So while it is reasonable to assume that Michelangelo discussed his ideas with people whose opinions he respected, it is highly unlikely that he allowed himself to be enslaved by any single, rigid theological framework.

It is well worth remembering that the visual structure of the Sistine Chapel ceiling namely, the monumental imaginary architecture that contains all of its imagery also plays a vital part in determining how that imagery is seen and felt and understood. It dictates the scale relationships of the various parts making, say, the prophets and sibyls loom large and the ancestors seem less important. Such discrepancies of scale are integral to the semantics of the ceiling. They ensure that the figure of Jonah, for example, is much more prominent more significant, more meaningful than that of any of the figures below him. Moreover, it seems certain that the imaginary architectural fabric, which plays such a crucial role both in the arrangement of the images and in the shaping of their meaning, was a structure Michelangelo himself both invented and insisted on. It is, as stated earlier, a painted version of the tomb for Julius II, which the artist had been planning for years. It was a form that he passionately wanted to create, whether in sculpture or painting. In the absence of evidence to the contrary, it must be assumed that he chose it for the ceiling and that he found most of the solutions that made it work.

It is clear from looking at the pictures themselves, which owe so little to the traditions of medieval and Renaissance art, and so much to the naked words of scripture itself, that Michelangelo read and reread the Old Testament continually while he was painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Condivi pointedly reports the fact in his biography, so it can be assumed that Michelangelo wanted it to be known. Between them, the biographies of Condivi and Vasari reveal a great deal about how Michelangelo wanted posterity to judge his achievements in the Sistine Chapel. Some of this information takes the form of direct assertion. Vasaris story about Michelangelo locking all his assistants out of the chapel makes it fairly clear that the artist wanted to be seen as the sole author of the work. Admittedly, it is not a story that has much bearing on the question of whether he was given theological guidance but Michelangelo had already answered that question with his letter to a friend, written in 1523, in which he recalled telling the pope that his first idea for the ceiling was a poor thing, and Julius II replying that Michelangelo could do whatever he wanted.