MICHELANGELO

AND THE POPES CEILING

ROSS KING

www.vintage-books.co.uk

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 1.0

Epub ISBN 9781446418833

www.randomhouse.co.uk

Published by Pimlico 2006

6 8 10 9 7 5

Copyright Ross King 2002

Ross King has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

First published in Great Britain in 2002 by

Chatto & Windus

First Pimlico edition published in 2003

Pimlico

Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW1V 2SA

www.rbooks.co.uk

Addresses for companies within The Random House Group Limited can be found at: www.randomhouse.co.uk/offices.htm

Random House UK Limited Reg. No. 954009

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781844139323

Contents

About the Author

Ross King is the author of Brunelleschis Dome, a highly praised account of how the Renaissance architect Brunelleschi constructed the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence (voted Non-Fiction Book of the Year by American Independent Booksellers in 2001). He has also written two novels, Domino and Ex Libris. He lives in Oxford.

For Melanie

Acknowledgements

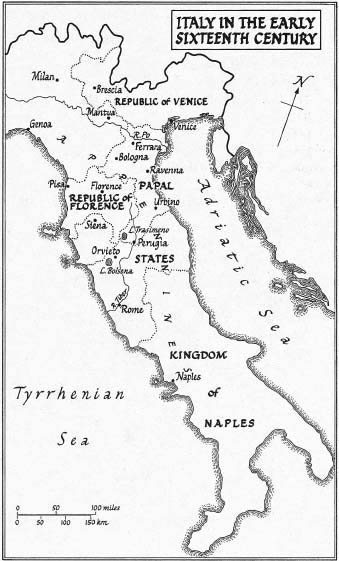

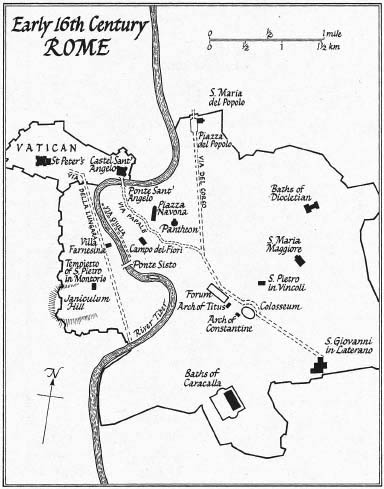

I wish to thank Professor George Holmes and Dr Mark Asquith, both of whom generously took the time to read the manuscript and offer comments and advice. My agent, Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson, likewise read manuscript drafts and provided his usual doses of enthusiasm and support. Christiana Papi assisted with several translations from sixteenth-century Italian. My brother, Dr Stephen King, doggedly hunted down and photocopied some elusive library material for me, and Reginald Piggott provided the maps and drawings. Lynne Lawner, thanks to a chance conversation, guided me to sources I would not otherwise have discovered. My editor, Rebecca Carter, deserves special mention. She encouraged the project from the outset and then steered it with patience and expertise through numerous drafts to completion. I also wish to thank my American editor, George Gibson, for his assistance and support.

I must also thank the curators and staff of the following institutions: the Bodleian Library; the British Library; the London Library; the Taylor Institution Library of Oxford University; and the Western Art Library of the Ashmolean Museum, now housed in the elegant new surroundings of the Sackler Library.

Finally, I wish to thank Melanie Harris, among numerous other reasons, for her companionship in Florence and Rome.

1

The Summons

THE PIAZZA RUSTICUCCI was not one of Romes most prestigious addresses. Though only a short walk from the Vatican, the square was humble and nondescript, part of a maze of streets and densely packed shops and houses that ran west from where the Ponte SantAngelo crossed the River Tiber. A trough for livestock stood at its centre, next to a fountain, while on its east side was a modest church with a tiny belfry. Santa Caterina delle Cavallerotte was too new to be famous. It housed none of the sorts of relics bones of saints, fragments from the True Cross that each year brought thousands of pilgrims to Rome from all over Christendom. However, behind this church, in a narrow street overshadowed by the city wall, there could be found the workshop of one of the most sought-after artists in Italy: a squat, flat-nosed, shabbily dressed, ill-tempered sculptor from Florence.

Michelangelo Buonarroti was summoned back to this workshop behind Santa Caterina in April 1508. He obeyed the call with great reluctance, having vowed he would never return to Rome. Fleeing the city two years earlier, he had ordered his assistants to clear the workshop and sell its contents, his tools included, to the Jews. He returned that spring to find the premises bare and, nearby in the Piazza San Pietro, exposed to the elements, a hundred tons of marble still piled where he had abandoned them. These lunar-white blocks had been quarried in preparation for what was intended to be one of the largest assemblages of sculpture the world had ever seen: the tomb of the reigning pope, Julius II. Yet Michelangelo had not been brought back to Rome to resume work on this colossus.

Michelangelo was thirty-three years old. He had been born on 6 March 1475, at an hour, he informed one of his assistants, when Mercury and Venus were in the house of Jupiter. Such a fortunate arrangement of the planets had foretold success in the arts which delight the senses, such as painting sculpture and architecture. a condition he was said to have fulfilled when the work was unveiled to an astonished public a few years later. Carved to adorn the tomb of a French cardinal, the Piet won praise for surpassing not only the sculptures of all of Michelangelos contemporaries but even those of the ancient Greeks and Romans themselves the standards by which all art was judged.

1. The Piazza Rusticucci, with the Castel SantAngelo in the background.

2. Michelangelo.

Michelangelos next triumph had been another marble statue, the David, which was installed in front of the Palazzo della Signoria in Florence in September 1504, following three years of work. If the Piet showed delicate grace and feminine beauty, the David revealed Michelangelos talent for expressing monumental power through the male nude. Almost seventeen feet in height, the work came to be known by the awestruck citizens of Florence as Il Gigante, or The Giant. It took four days and considerable ingenuity on the part of Michelangelos friend, the architect Giuliano da Sangallo, to transport the mighty statue the quarter-mile from his workshop behind the cathedral to its pedestal in the Piazza della Signoria.

A few months after the David was finished, early in 1505, Michelangelo had received from Pope Julius II an abrupt summons that interrupted his work in Florence. So impressed was the Pope with the