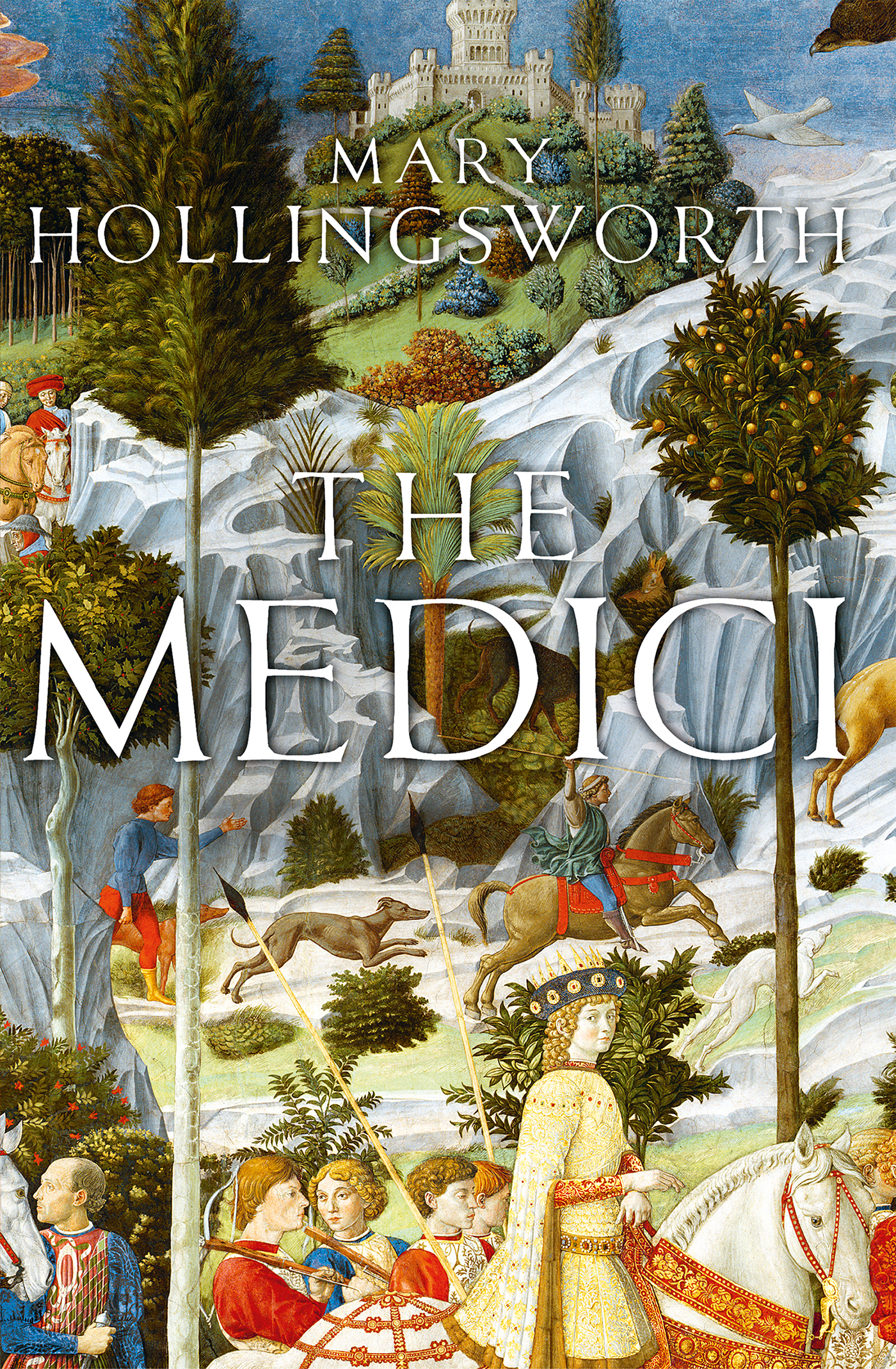

THE MEDICI

Mary Hollingsworth

www.headofzeus.com

WEALTHY BANKERS ,

WISE POLITICIANS , PATRONS OF THE ARTS ,

GLITTERING DUKES ...

...the Medici family ruled Florence from the fifteenth to the eighteenth century. As enlightened rulers of that city, they created an environment where art and humanism could flourish, thereby fostering and inspiring the birth of the Italian Renaissance.

Or so runs the traditional telling of the Medici story. Munificent patrons though they certainly were, Mary Hollingsworth argues that the claim the Medici were fathers of the Renaissance, and Florence its cradle, is in large part a fiction; a legend created in the sixteenth century to enhance the Medici name and a myth that has overshadowed the contributions made by the Church and by the rulers of other Italian cities. Drawing on a plethora of documents, including state papers, inventories, wills and banking records, she reveals the Medici to be as devious as the Borgias: tyrants loathed in the city they illegally made their own and which they beggared in their lust for power.

This is the definitive account of the Medici: comprehensive in its historical scope, painstaking in its research, and gripping in its narrative verve. Mary Hollingsworth explodes our gilded image of the Medici to reveal how they exploited the arts as propaganda for their cause and created the myth that has successfully masked our knowledge of an extraordinary and entirely unscrupulous family.

Contents

For my mother

Elizabeth Hollingsworth

19222017

Jacopo Pontormo , Cosimo de Medici , c . 151819 (Florence, Uffi zi), an idealized portrait celebrating the founder of the Medici dynasty. Cosimo was a man who dishonestly amassed a fortune and used it to subvert the Florentine republic, bribing his way to power with the help of his private army .

Pontormo , Cosimo de Medici the Elder ; Uffizi, Florence / Google Cultural Institute / Wikimedia Commons .

Names and Dates

The Medici, like other families in medieval and early modern Italy, often chose to name their children after their parents or grandparents, a habit that causes much confusion to modern historians. To help the reader identify the character correctly, I have followed the Italian convention of giving both Christian name and patronymic where necessary. Thus, Lippo di Chiarissimo, for example, refers to Lippo son of Chiarissimo.

Another source of confusion concerns the calendar and the dating of events. In Rome, New Years Day was 1 January; but in Florence the year did not begin until 25 March, the Feast of the Annunciation. I have converted all relevant dates to conform to the modern style.

Money

In common with the other states that existed in Italy before the unification of the country, Florence had its own currency, the lira (1 lira = 20 soldi = 240 denari ), a silver-based coinage that was used for everyday transactions, such as buying food or paying wages. For more weighty business paying dowries, for instance, or assessing wealth for tax purposes, or international trade the Florentines used their florin, a gold coin that was recognized across Europe. Over the years the value of the lira declined steadily in relation to the florin: when the florin was first minted in 1252 it was worth 1 lira ; by 1500 its price had risen to 7 lire . Wherever possible, I have given the value of the sums involved in florins.

Other currencies are also mentioned in this book, notably the gold ducats of Venice and Rome, and the gold scudo (pl. scudi ), which replaced the Roman ducat in 1530. These gold coins were broadly similar in value to the Florentine florin.

A CITY

UNDER SIEGE

Florence in ashes

rather than under the Medici

Midsummers Day, 24 June: the Feast of St John the Baptist, patron saint of Florence, and the highlight of the Florentine year. San Giovanni, as the holiday was known, was traditionally a day for best clothes and parties, when dining-tables would be piled high with good food and the air would be filled with the sounds of music, chatter and laughter. Out on the streets, the people could inspect the eye-wateringly expensive goods on show at the stalls of the guilds, watch gaudy parades of floats and marvel at spectacular firework displays. Buskers and tumblers hoped to profit from the holiday mood, and there were bets to be placed on the annual horse race through the narrow cobbled thoroughfares, and tickets to be bought for the bullfights, mock battles and football matches. Standing on their balconies or jostling on the pavements, the Florentines could witness the great procession of the citys churchmen making their way through the streets, singing and chanting, sprinkling holy water, shaking their thuribles to release clouds of incense and blessing the crowds, while the church bells rang out in a noisy, joyful clamour.

On the morning of the feast, the Florentines celebrated the power and wealth of their city in magnificent style, in the piazza in front of the Palazzo della Signoria the seat of their republican government. Gathered there would be Florences leading citizens and guild consuls, officials of the Mint with their bags of gold florins, foreign lords, knights and ambassadors riding superbly caparisoned horses, and, most thrilling of all, the delegations from Florences subject towns and territories, who knelt in homage to the nine men of the republics ruling council, the Signoria .

In 1530, however, things were very different. That year, San Giovanni was a funereal affair. There were no banquets nor bullfights, no laughter nor music, just one solemn procession. The sombre crowds who gathered on the streets that morning watched in silence as the Signoria and other government officials walked barefoot from the Palazzo della Signoria to the cathedral, dressed in brown, the colour of mourning. They carried lighted tapers behind a procession of treasured relics, their aim to implore God to aid their beleaguered city. Florence was under siege. Camped around the walls, in rows of tents that stretched as far as the eye could see, were 30,000 enemy soldiers and their paymaster was one of Florences own sons: Giulio de Medici, now Pope Clement VII.

Three years earlier the Florentines had voted overwhelmingly to banish the Medici from the city, but Clement VII was determined to reverse this quite lawful decision, whatever the cost. He did not regard Florence as an independent republic but as the personal fiefdom of his own family; and his goal was to install his illegitimate son as its ruler. He had powerful allies. The troops outside the city gates were part of the mighty army of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, who had agreed to help Clement VII in his naked bid for power. Pope and Emperor had also used their political muscle to ensure that Florences allies France, Venice and Ferrara now deserted its cause. Florences subject towns had been captured and its supply lines almost entirely cut off, depriving the city of food and munitions. Only the army remained to defend the city from the Medici, and it was a puny force of 12,000 men, only half of whom were professional soldiers, the rest being poorly trained militiamen.