To Arabella

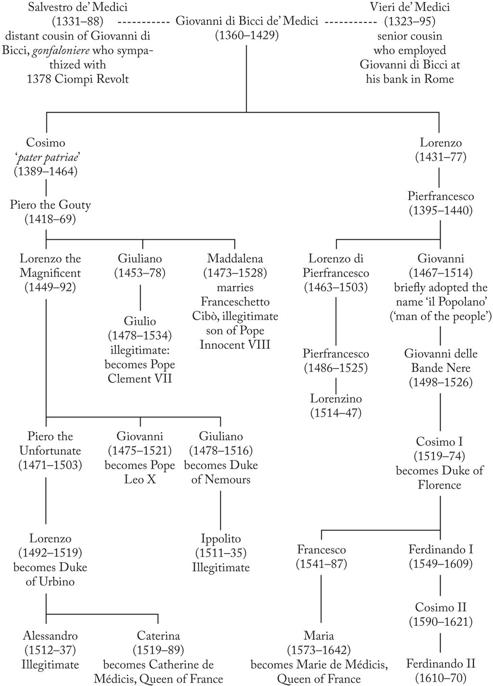

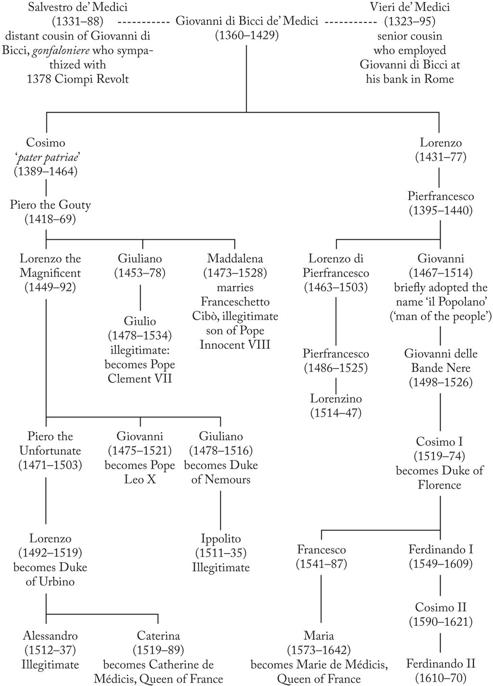

MEDICI FAMILY TREE

PROLOGUE

B ETWEEN THE BIRTH OF Dante in 1265 and the death of Galileo in 1642, something happened which would transform the entire culture of western civilization. Painting, sculpture and architecture would all visibly change in such a striking fashion that there could be no going back on what had taken place. Likewise, the thought and self-conception of western European humanity would take on a completely new aspect. Sciences would be born, or emerge in an entirely new guise. Part of this cultural transformation would be influenced by the rediscovery of the pre-Christian literature of Ancient Greece and Rome, but much of it would result from how the novelty of this earlier essentially pagan outlook came into conflict with, and was assimilated by, the society in which it was rediscovered.

The collapse of the Roman Empire just under a millennium previously had left Europe largely in a state of historical and intellectual desolation often referred to as the Dark Ages, with the few persisting centres of learning mainly confined to isolated monasteries. Gradually, with the encouragement of Christianity, this dark age evolved into the medieval world. Consequently, the combination of intellect and faith came to be regarded as such a precious commodity, preserving civilization itself, that a widespread orthodoxy prevailed in order to protect it. However, over the centuries this orthodoxy permeated all aspects of life to the point where it dominated intellectual debate, and a state of cultural stasis began to prevail.

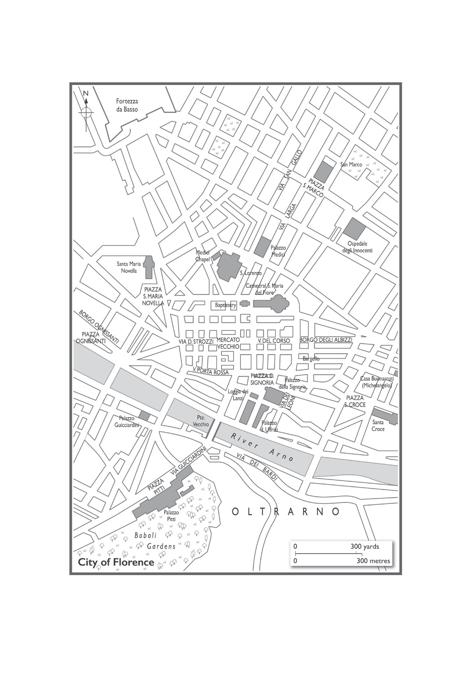

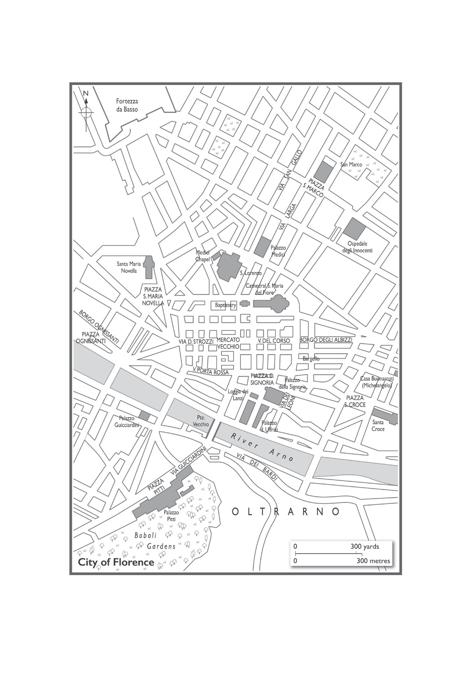

The ideas which broke this mould largely began, and continued to flourish, in the city of Florence, in the region of Tuscany in northern central Italy. Such novel concepts, which placed an increasing emphasis on the development of our common humanity rather than other-worldly spirituality would coalesce into what came to be known as humanism. As its name suggests, this philosophical attitude emphasizes our individual humanity and its central place in our lives, rather than relying upon divine providence and concentrating on metaphysical matters. Its founding insight can be seen in the assertion by the fifth-century BC Greek philosopher Protagoras: Man is the measure of all things. As such, humanism led to an increased self-understanding, and a radical extension of our psychological self-knowledge. We gained a clearer picture of ourselves, and in doing so were inclined to seek more rational solutions to our problems rather than reverting to the power of prayer.

This philosophical outlook would eventually spread across Italy, yet wherever it took root it would retain an element essential to its origin. And as it spread further across Europe, this element would remain. Inevitably, other ingredients also entered this rich mix. Amongst the trading cities of northern Europe humanism would flourish and develop, absorbing local characteristics. In less cosmopolitan kingdoms it would take on a more static element of empty show. At the same time, more abstemious, narrow-minded populations could not, or would not, tolerate such ostentation and luxury. Despite such apparent resistance, elements of the new humanism would also subtly permeate even their repressive mental outlook. This was in many ways the period in which the modern era began. The way we think, the way in which we regard ourselves, our modern notion of progress these, and much more, originated from the humanist era.

Transformations of human culture throughout western history have remained indelibly stamped by their origins, no matter how they have evolved beyond these local beginnings. The Reformation would always retain something of central and northern Germany in its many variations. The Industrial Revolution soon outgrew its British origins, yet also retained something of its original template. Closer to the present, the Digital Revolution which began in Silicon Valley remains indelibly coloured by its Californian roots. It is my aim to show how Florence, and the Florentines, played a similar role in the nurture and evolution of the Renaissance.

CHAPTER 1

DANTE AND FLORENCE

I N 1308, THE EXILED Florentine poet Dante Alighieri described how, midway through his life, he found himself lost amidst a dark wood, with no sign of a path. He had no idea how he had arrived where he was. His mind was fogged; it was as if he had woken from a deep slumber. After walking for a while, filled with trepidation, he came to the foot of a hill at the end of a valley. Raising his gaze, he saw the high upland bathed in the rays of the dawning sun. He began to climb the barren slope, finally pausing for a while to rest his weary limbs. Not long after restarting, he found his way blocked by a gambolling leopard, its dappled fur rippling as it skipped before his feet. By now the sun had begun to rise in the heavens, and the sight of this fine frisking beast in the morning sunlight inspired Dante with hope. But this suddenly vanished when he caught sight of a roaring lion charging towards him. No sooner had he escaped from this fearful beast than he encountered a lean and slavering, hungry she-wolf, which caused him to retreat in terror down the slope, back towards the dark silence of the sunless wood. As he stumbled headlong downwards, he saw before him a ghostly form.

Help me! cried Dante. Whatever you are man or spirit.

The shadowy figure replied, No, I am not a man. Though once I was. I lived in Rome, during the reign of the good Augustus Caesar, in a time of false and lying gods. I was a poet, who sang of Troy

Canst thou be Virgil? The very one who has inspired me throughout my own life as a poet?

I am he.

Oh, save me from this ferocious wolf.

She lets no one pass, and devours all her prey. She will gorge on all who try to get by her, until one day the Greyhound will come. He will hunt her through every city on earth. In the end he will drive her back to Hell, whence she escaped after Envy set her free.

Then Virgil continued: I think for your own good that you should follow me. Let me be your guide, and pass with me through an eternal place, where you will hear the hideous shrieks of those who cry out to be released, those who beg for a second death but are damned to torment for evermore. Next you will come to another place and gaze upon those who are happy amidst the fire, because they know that one day they will be purged and rise to take their place amongst the blessed. Then, if you wish, you too can see this blessed realm and its Emperor, to which I cannot lead you, because I was a rebel against his law. From that point on, only another spirit, far worthier than I, can lead you through Paradise.

Dante replied: Poet, I implore you in the name of that God you never knew, lead me through that place you have described, as far as St Peters Gate, which stands at the entrance to Paradise.

So Virgil moved on, and Dante followed him.

Thus opens Dantes La Divina Commedia (The Divine Comedy), now widely regarded as the finest poem in the canon of western literature. Its full ambition and scope are realized by the imagination which Dante lavishes on his descriptions of the land of the dead and the souls he encounters there. In many ways, his poem is an outline of the past world and many of its leading historical figures. It is imbued with the spirit of the medieval era, yet Dantes psychological insight into the characters he encounters, and the vividness of their described afterlife, prefigures the coming age of the Renaissance. Each soul he meets on his journey is rewarded according to the life he or she has lived during their time on earth. In this, Dantes thoughts are thoroughly medieval: this life is but a preparation for the life to come, when we will be rewarded, purged or damned, according to our just deserts. Yet although this divine comedy is suffused with the theology of Catholic orthodoxy, as well as the Aristotelian philosophy which underpinned so much of its teaching, the poem is instantly recognizable as being of the modern era.

Next page