Dedication

In memory of Jacques Le Goff

Copyright page

First published in French as Sensible Moyen ge: Une histoire des motions dans lOccident mdival ditions du Seuil, 2015

This English edition Polity Press, 2018

Foreword Barbara H. Rosenwein, 2018

This work received the French Voices Award for excellence in publication and translation. French Voices is a program created and funded by the French Embassy in the United States and FACE (French American Cultural Exchange).

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-1465-6

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-1466-3 (pb)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Boquet, Damien, author. | Nagy, Piroska (College teacher) author.

Title: Medieval sensibilities : a history of emotions in the middle ages / Damien Boquet, Piroska Nagy.

Description: Medford, MA : Polity Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017052168 (print) | LCCN 2017054820 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509514694 (Epub) | ISBN 9781509514656 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509514663 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: EmotionsHistory.

Classification: LCC BF531 (ebook) | LCC BF531 .B66 2018 (print) | DDC 152.409/02dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017052168

Typeset in 10 on 11.5 pt Sabon by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited

Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Foreword

Barbara H. Rosenwein

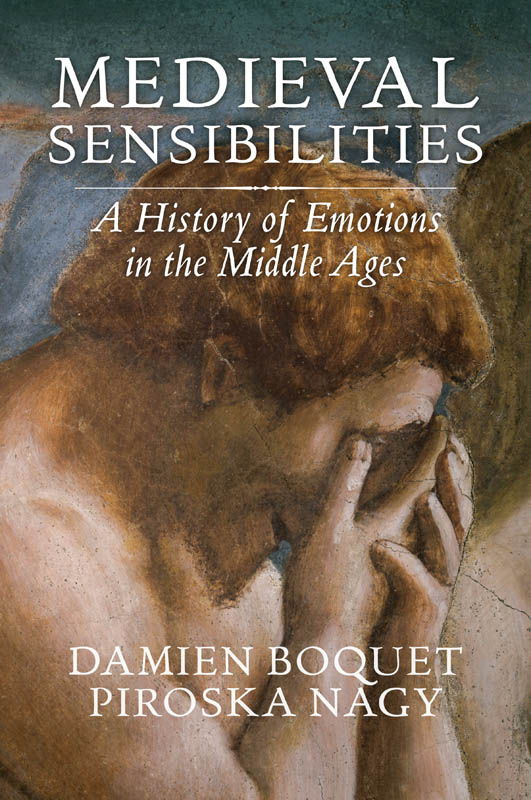

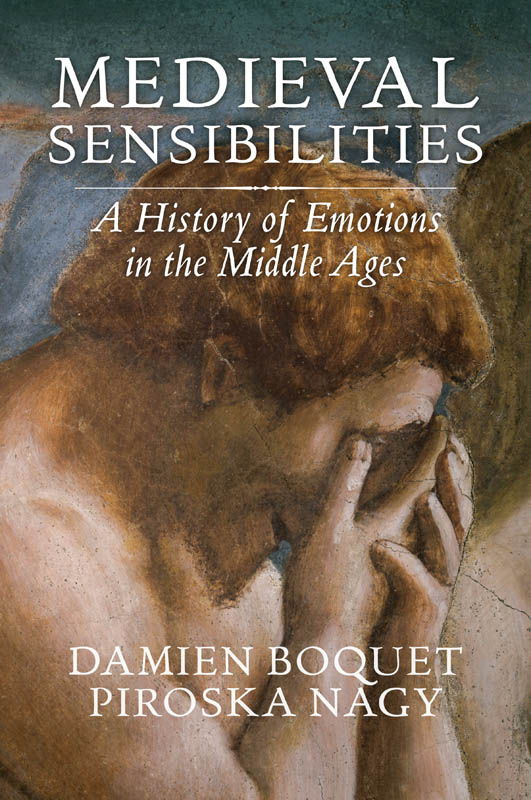

What were the emotional consequences of the Christianization of Europe? In Medieval Sensibilities, Damien Boquet and Piroska Nagy bring to the English-speaking audience the fruits of their long reflection on this question. They show how, far from being a stagnant Middle Age standing between the learned ancient world and discontented modernity, the period was in constant affective ferment. Social and economic changes in themselves brought new sensibilities and needs. These new milieus, drawing on and filtering, but also adding to, the many intellectual traditions increasingly available to an expanding clerical elite, transformed their thoughts about Christ's Passion. In turn, these new understandings, taught in the schools, proclaimed in the churches, preached on the streets, and acted out by rulers, transformed the feelings and behaviours of Europeans in general.

Theologies of the Passion were thus put into practice. As Boquet and Nagy show, the emotions implied by new understandings of Christ's human nature and passion came to shape the very ways in which medieval people lived their lives. Initially, this was not the case; the affective implications of the Christian God were at first largely the monopoly of one man (Augustine). But they soon became the focus of an ever-expanding religious elite, taken up first by men and women in hermitages and monasteries and then, eventually, becoming the concern of people in every walk of life.

This book is itself the fruit of a different sort of progressive inclusion. The authors began their careers working separately. Boquet's dissertation, which became his first book, was on the affective life and thought of Aelred of Rievaulx, a twelfth-century monk and abbot who wrote extensively on the meaning of love and friendship. Nagy's early work was on the gift of tears: she unravelled the tangled threads involved in the idea that crying could have salvific meaning. When they began to work together, they founded a website, emma.hypotheses.org, dedicated to the study of medieval emotions in tandem with the scholarship of the humanities and social sciences. They organized conferences to which they invited speakers to consider medieval sensibilities from every point of view. Together the two scholars edited and published the results of these conferences in books ranging in topic from the political uses and meanings of emotions to the role of the body to intellectual history.

Medieval Sensibilities reflects that prior work and goes beyond it. Its emphasis on the suffering Christ as the starting point for medieval sensibilities draws on the authors interest in the role of the body in experience and expression. In taking up theologians like Augustine, Anselm of Canterbury, and Thomas Aquinas, they distil the fruits of long rumination on medieval theories of the passions. When considering the politics of princely emotions, they exploit their own and others work on performativity. Above all they weave together these and other topics in a coherent narrative covering the entire medieval period.

The story really gets underway with the missionizing work of the Irish monk Columbanus. Charismatic and fiercely determined, he brought the monastic ideals of affective restraint first to the Frankish royal court and thence to the elites. A still more thorough diffusion of Christian values occurred under Charlemagne (d. 814) and his early successors, as churchmen incorporated Christianized notions of the passions into masses for monks and books for the laity. Learned clerics turned the idea of Christian love, caritas, into an ideal of worldly love as well, as if the Christian community could come together through the bonds of charity.

Secular society did not live up to these expectations, except in its cultivation of vernacular literature, which expressed the ideals of measure and restraint, put emphasis on joy, and celebrated longing. But in the monastery the accent on love became something of an obsession. Eleventh- and twelfth-century monks were in their era what neuroscientists are in our own: recognized experts on emotions. Above all, the monks considered themselves and were seen as the go-to authorities on love. Hermits, ascetics, Cistercians, even some secular clerics parsed the various forms of love, explored their causes and effects, elaborated ways to show affection, tenderness, and compassion, and taught themselves and others how to practise the right that is, Christianized emotions. They elaborated on new forms of meditation, dwelling on and participating in the life, feelings, and travails of Christ. Just as significantly, they unabashedly celebrated love among friends, so that what had hitherto been seen as the secular institution of friendship became as holy as love of God and neighbour.

Next page