Contents

Guide

Pages

For Mlanie

dolce citt

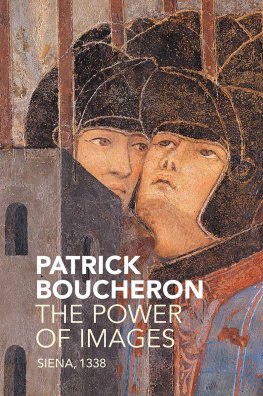

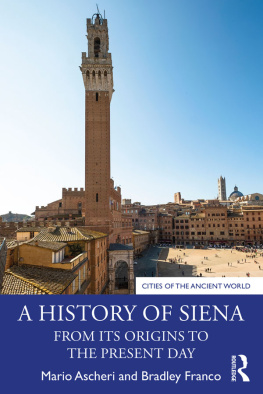

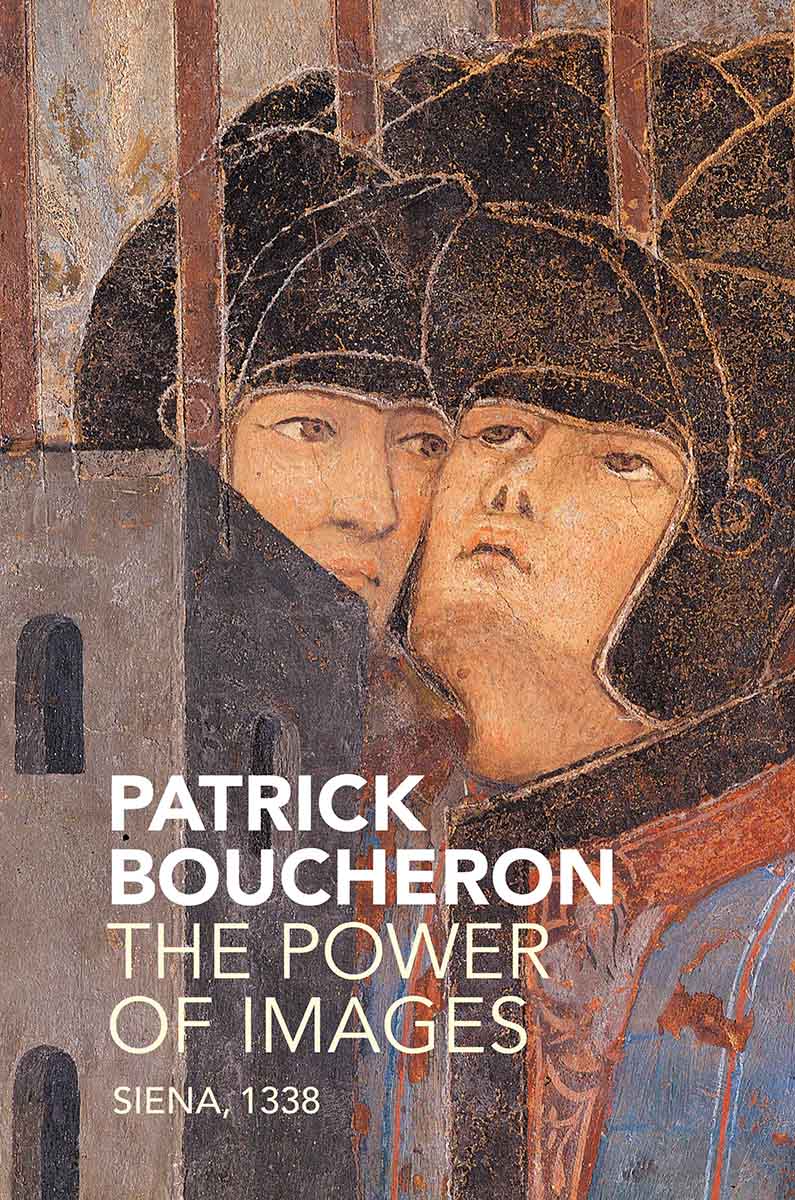

The Power of Images

Siena, 1338

Patrick Boucheron

Translated by Andrew Brown

polity

First published in French as Conjurer la peur. Essai sur la force politique des images. Sienne, 1338 ditions du Seuil, 2013

This English edition Polity Press, 2018

This book is supported by the Institut franais (Royaume-Uni) as part of the Burgess Programme.

This work received the French Voices Award for excellence in publication and translation. French Voices is a program created and funded by the French Embassy in the United States and FACE (French American Cultural Exchange).

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-1293-5

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Names: Boucheron, Patrick, author. | Translation of: Boucheron, Patrick. Conjurer la peur.

Title: The power of images : Siena, 1338 / Patrick Boucheron.

Other titles: Conjurer la peur. English

Description: Medford, MA : Polity Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017042160 (print) | LCCN 2017042620 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509512935 (Epub) | ISBN 9781509512898 (hardback) | ISBN 9781509512904 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Lorenzetti, Ambrogio, 1285-approximately 1348--Criticism and interpretation. | Palazzo pubblico (Siena, Italy) | Politics in art. | Mural painting and decoration, Gothic--Italy--Siena. | Mural painting and decoration, Italian--Italy--Siena--14th century. | Siena (Italy)--History--Rule of the Nine, 1287-1355.

Classification: LCC ND623.L75 (ebook) | LCC ND623.L75 B6813 2018 (print) | DDC 759.5--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017042160

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Foreword

Patrick J. Geary

For much of the twentieth century, as France transformed from a predominantly agricultural to an industrial society, the centre of gravity in French mediaeval history was the countryside. From Marc Blochs French Rural History (1931) through Georges Dubys classic study of the Mconnais (1953), to Pierre Touberts monumental study of mediaeval Latium (1973), French scholars and the French reading public were obsessed with the deep structures and rhythms that defined a rural society disappearing before their eyes. Patrick Boucheron, successor at the Collge de France of his mentor Toubert and Touberts mentor Duby, is a historian of the city: He was formed in and around Paris, first at the venerable Lyce Henri IV, subsequently at the cole normale suprieure Fontenay-Saint-Cloud (since transferred to Lyon), where he studied and later returned to teach, then at the University of Paris I Panthon-Sorbonne, at which he taught before his election to Collge, where since 2016 he has held the chair of the history of powers in western Europe, thirteenth to sixteenth centuries.

His love of Paris and his faith in its complex urban fabric, its people and its culture, are clear in his inaugural lecture at the Collge de France delivered shortly after the Bataclan theatre massacre in November 2015, where, quoting his great predecessor Jules Michelet, he affirmed that Paris represents the world.

Not surprisingly, then, he has been drawn, as have generations of Italian, German, British and American scholars of the Italian communes, to the campo of Sienna, to its Palazzo Pubblico, and within, to its Sala della Pace, on whose walls, in 1338, Ambrogio Lorenzetti painted the stunning triptych now known as the Fresco of Good Government, but which, as Boucheron points out, is not a fresco and, for centuries, was identified not with good government but rather with the contrasting images of war and peace.

In this rhetorically crafted and carefully constructed book, Boucheron both draws on and spars with the vast literature already dedicated to interpreting Lorenzettis work, principally that of Rosa Maria Dess and Quentin Skinner, in an attempt to approach these paintings with fresh eyes. Or, better, to reflect on the impossibility of approaching them, since, as he writes, today we cannot see them as they were meant to be seen, but only as vestiges. Not only is the image of war on the western wall badly damaged, not only are the images on the eastern and northern walls distorted by retouching and overpainting through the centuries, but the substantial changes in the building itself make it impossible to move through space to encounter them as one did in the fourteenth century. Thus, the role that Boucheron undertakes, that of the historian, is to guide the reader into an inaccessible and impossibly distant world, but one whose challenges and fears remain disturbingly actual in the twenty-first century.

For Boucheron, the fundamental misunderstanding of these powerful paintings is precisely to see in them an allegory of good and bad government, a visual representation of political ideology derived from Aristotle and filtered through his commentators across the centuries. Rather, Boucheron seeks to ground the paintings in the precise context of Siena in the third decade of the fourteenth century. The Sala della Pace was the chamber in which Sienas principal governing body, the Nine, met in deliberation. When the Nine commissioned Lorenzetti to depict war and peace, their concerns were not with a generalized theory of government but with the very concrete fear of civil strife and its ability to destroy the social fabric that bound together Sienas often fractious society. But even more, they feared the apparent alternative to civil strife: the overthrow of communal government by unitary lordship, the rise of the signoria, as was happening across northern Italy. The original title of Boucherons book captures this exactly: Conjurer la peur to ward off fear. The image of peace, which covers the eastern wall, shows peace not simply as the absence of war, but rather as the concrete effects of social justice: harmony, a harmony that can bind together all citizens. The western wall shows the results of war, but war in the mediaeval sense of guerra, that is, in the first instance, feud, factional conflict, which threatened, even more than external war, to destroy all that is good in the city. In between, on the north wall, separating war and peace, are the figures of the government of the city, the importance of peace, strength and prudence, magnanimity, temperance and justice, exercised by the commanding figure of the commune of Siena itself, the collective guarantor of peace and the defence against factionalism and, ultimately, the tyranny of one-man rule.