Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

ALSO BY PATRICK BOUCHERON

France in the World (editor)

The Power of Images: Siena, 1338

Originally published in French as Un t avec Machiavel in 2017 by ditions des quateurs, Paris.

Copyright ditions des quateurs / France Inter, 2017

English translation copyright Willard Wood, 2018

Production editor: Yvonne E. Crdenas

Text designer: Julie Fry

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 267 Fifth Avenue, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10016. Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Boucheron, Patrick, author. | Wood, Willard, translator.

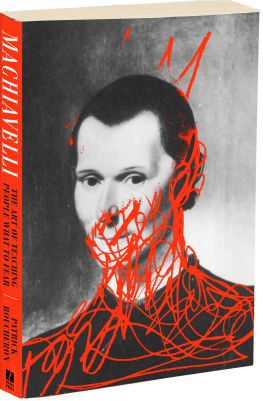

Title: Machiavelli : the man who taught the people what they have to fear / Patrick Boucheron; translated from the French by Willard Wood.

Other titles: Un t avec Machiavel. English

Description: New York : Other Press, 2020. | Originally published in French as Un t avec Machiavel in 2017 by ditions des quateurs, Paris.

Copyright ditions des quateurs / France Inter, 2017

English translation copyright Willard Wood, 2018 T.p. verso. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019025723 (print) | LCCN 2019025724 (ebook) | ISBN 9781590519523 (hardcover : acid-free paper) | ISBN 9781590519530 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Machiavelli, Niccol, 14691527. | Machiavelli, Niccol, 14691527Criticism and interpretation. | Political scientists Biography. | Political ethics. | Political science Italy.

Classification: LCC JC 143. M 4 B 6413 2020 (print) | LCC JC 143. M 4 (ebook) | DDC 320.1092 dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019025723

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019025724

Ebook ISBN9781590519530

v5.4

a

CONTENTS

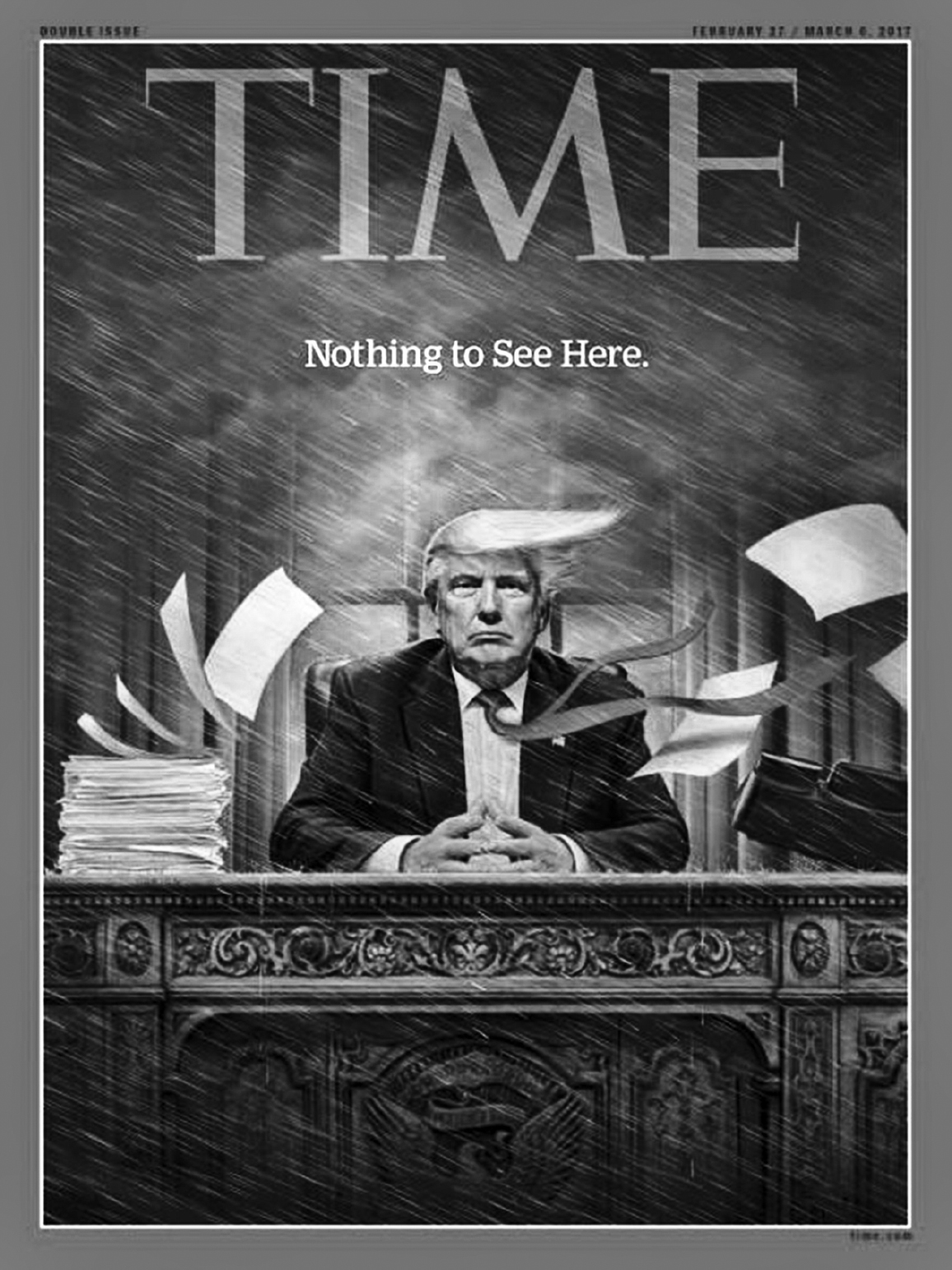

Cover of Time magazine, February/March 2017

INTRODUCTION

THE ART OF TEACHING PEOPLE WHAT TO FEAR

REAL POWER IS I dont even want to use the word fear. This sentence could have been written by Niccol Machiavelli. It was spoken by Donald Trump in March 2016 when Trump was still only a candidate for the U.S. presidency, and these words now appear as the epigraph to Bob Woodwards book Fear: Trump in the White House. Is a more off-putting introduction to our subject imaginable? If we are tempted to assign words spoken by Donald Trump to Machiavelli, its not just because many Western leaders have, and for a long time, bolstered their sense of their own power by affecting a cynical and crafty tone in the belief that it represents the last word in Machiavellian thought. Its because we literally dont know what to think of Machiavelli. Should we admire him or not, is he with us or against us, and is he still our contemporary or is what he says ancient history? This little book doesnt pretend to resolve these questions; nor is it addressed to those who will read it to feel that they have right on their side whether that side is answerable to justice or to power. On the contrary, this book tries to stay in that uncomfortable zone of thought that sees its own indeterminacy as the very locus of politics.

I should, at this stage, give a few explanations about this book who is speaking, and to whom. I dont consider myself a historian of political ideas, but I approached Machiavelli a decade ago, yoking him with Leonardo da Vinci in an essay on contemporaneousness. Unexpectedly, I found Machiavelli a useful guide and support Id almost say a faithful friend, one whose intelligence never failed me. This might seem overly sentimental if it didnt echo Machiavellis own image of discoursing with the ancient Greeks, as he put it in his famous letter to Francesco Vettori in 1513, where he describes writing The Prince: I am not ashamed to converse with them and ask them for the reasons for their actions. And they in their full humanity answer me.

My conversations with Machiavelli became more regular and fruitful as I approached topics of which the Florentine author was, in his day, the most clear-sighted analyst. This happened first as I researched the political meaning of the architecture of the quattrocento. Machiavelli taught me to see it less as a representation of power than as a machine for producing political emotions: persuasion, in the public buildings of the republican city-states; and intimidation, in the fortified strongholds that the princes built to keep those states in line. It happened again when I was trying to understand how the political instability of Renaissance Italy, riven with conspiracies and coups dtat, represented a structural element of princely power, which inevitably uses violence as the foundation of law. In every case, Machiavelli proved a worthy brother-in-arms who, because he had thrown light on his own times, threw light on ours proving himself a contemporary in the very best sense.

During the summer of 2016, I gave a series of daily talks on French public radio in which I tried to articulate this capacity of Machiavellian thought to sharpen our understanding of the present. This little book collects those texts, which in their biting brevity and direct address attempt to harmonize in style with Machiavelli not simply his manner of writing but his art of thinking, which brings to a flash point the fusion of poetry and politics.

Only one of these talks was not broadcast on the France Inter network during the summer of 2016, the fifth, focused on Machiavellis reading of Lucretiuss De natura rerum, a dangerous and deviant book that makes the world jump its rails and come off its hinges. The plan was to air the episode on Friday, July 15, but it was swallowed up by the sorrow, anger, and numbness that followed the terrorist attack on the Promenade des Anglais in Nice on July 14, Frances national holiday, when eighty-six people were killed and more than four hundred wounded. Although this book restores the text to its original place, there is still a gap left by the lasting stamp of fear.

Is that why I have chosen to give prominence in the books American edition to the politics of fear? Not solely. As I write this preface, I am remembering a dialogue that I had with the political scientist Corey Robin, the author of a major book in 2004, Fear: The History of a Political Idea. One day, he wrote, the war on terrorism will come to an end. All wars do. And when it does, we will find ourselves still living in fear: not of terrorism or radical Islam, but of the domestic rulers that fear has left behind. Our discussion, which led to the publication in 2015 of Lexercice de la peur: usages politiques dune motion (Spreading fear: the political uses of an emotion), asked whether the American way of fear might be exported around the world. We touched on Hobbes, of course, de Tocqueville and Hannah Arendt, but also Machiavelli, who continually inquired about the fears of those who govern: What makes them truly afraid? When justice stops being effective (or when crimes of corruption stop being punished) and when political violence is no longer a threat, there is nothing left to cause fear in those who govern shamelessly, that is, buoyed by a mood they arent in control of and that no one is on hand to countervail. What will then happen to the republic? This question inevitably arises when anxiety is felt about democracy, because the republic loses its stability when it no longer reflects a pacified equilibrium between the different fears that divide it.