THE GLORIFICATION OF GOD

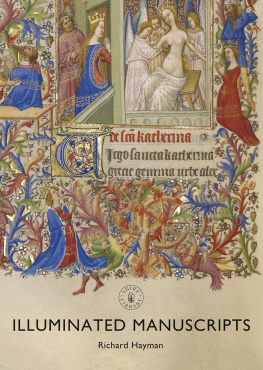

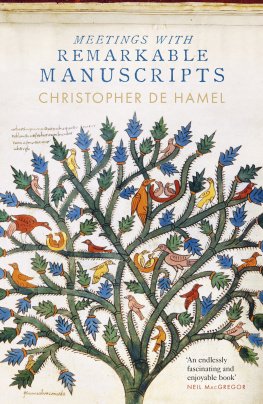

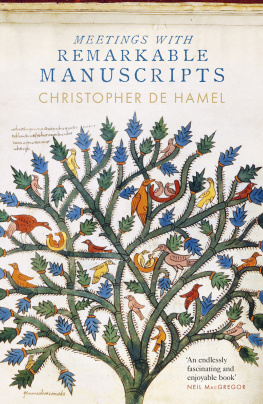

I lluminated manuscripts are the great secret history of the Middle Ages. The masterpieces of the period, ranging from the Book of Kells produced by Irish monks on Iona in the eighth century to the sumptuous Les Trs Riches Heures made for the Duc de Berry in the fifteenth century, rank with the cathedrals of Europe as major cultural landmarks of the Middle Ages. They have been enjoyed in facsimile editions and exhibitions have displayed single pages in glass cabinets, but few people have ever had the privilege of turning the pages of an original illuminated manuscript. In a world where art is essentially a public affair, illuminated books were private, intimate works that were mainly experienced in silence and solitude. Medieval illuminated manuscripts have always had the connotation of hidden treasure and have retained a special mystique.

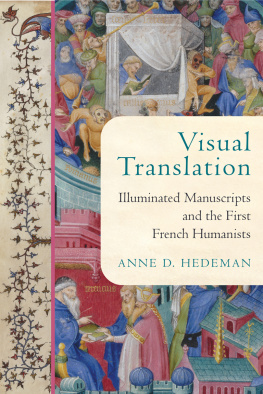

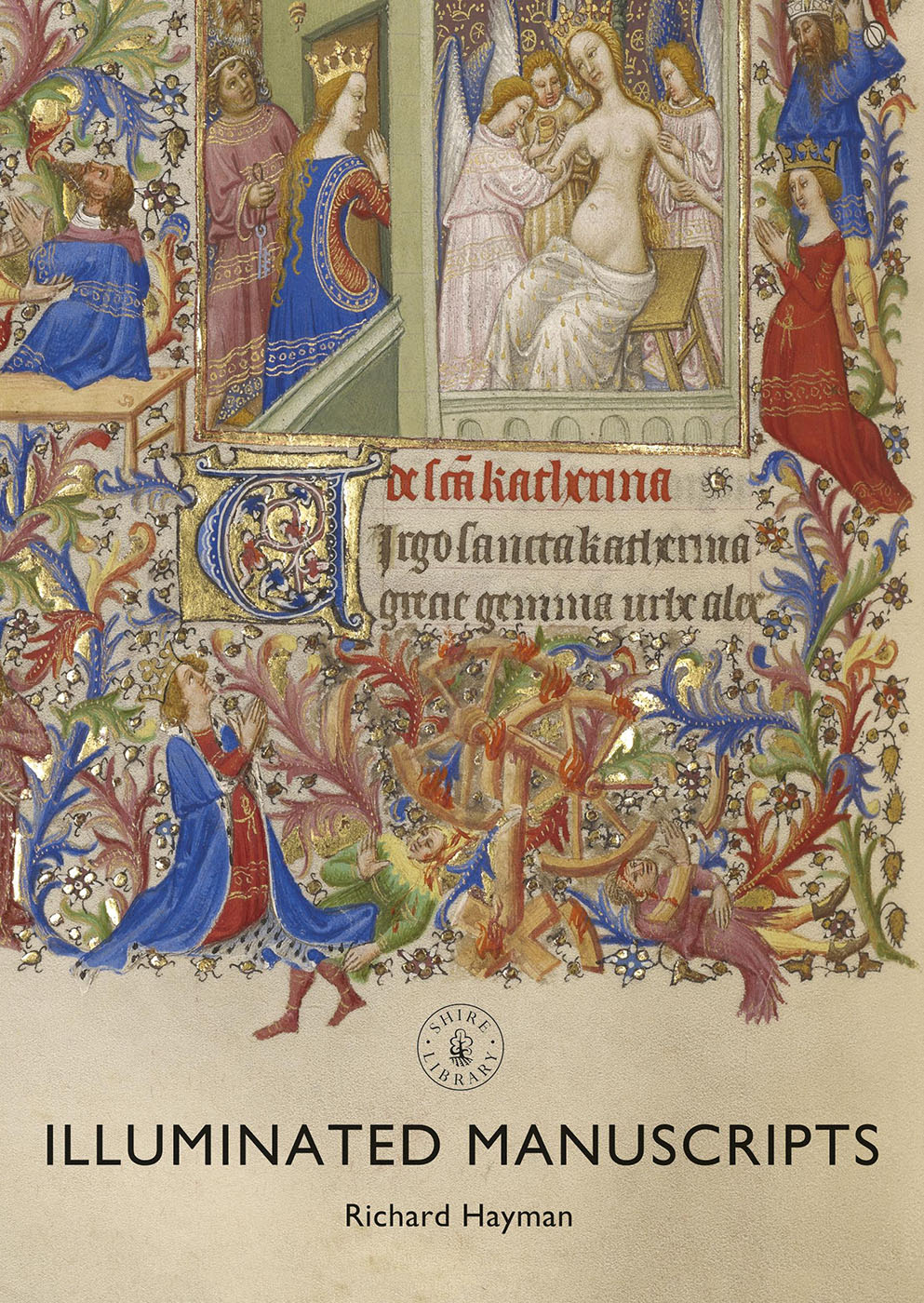

Les Belles Heures, commissioned by the Duc de Berry and completed in 1409, is one of the most beautiful objects to have been created in the Middle Ages.

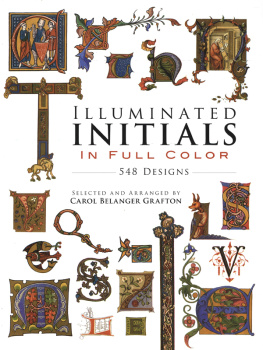

Manuscript means written by hand and covers every type of book produced in the Middle Ages before the invention of the printing press. The illustrations became known as illuminations because gold and silver leaf combined with bright pigments to produce a rich shimmering effect on the page. In fact, some manuscripts were so richly illuminated with gold leaf that they were known as a Codex Aureus, a golden book. Illuminated manuscripts are characteristic of a period that was rich in visual expression. The page was adorned with decorative, narrative and devotional images just as sculptures peopled the external walls of churches and painting adorned the interior.

Christ in Majesty, surrounded by the four Evangelists and Old Testament prophets and patriarchs, is an illumination in gold leaf and tempera from a German Missal, or book of the Mass, of the 1170s.

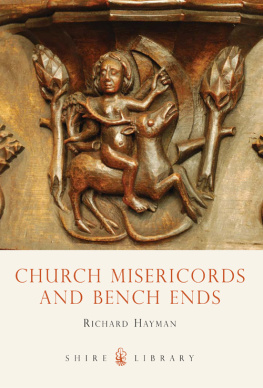

The range of books produced in the Middle Ages includes sacred texts as well as secular works such as histories, philosophical works and Arthurian romances. Dantes Inferno and Chaucers Canterbury Tales both first appeared in manuscript form. The majority of books, however, were religious in content. Christianity is the religion of the book (in classical antiquity there was no equivalent sacred text to the Christian Bible). The Bible is the physical embodiment of Gods word and in the Middle Ages was a sacred object in its own right. We have forgotten the extent to which objects were important in medieval belief as relics made the existence of saints seem more real so a beautiful Bible or other devotional book affirmed the truth of Gods message.

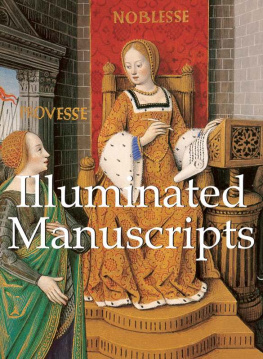

At least until the thirteenth century books were mainly produced and consumed by religious men and women. One of the reasons that book production eventually flourished beyond the monastic cloister was that lay people started to purchase and read books as an act of private devotion, an expression of popular piety that grew steadily throughout the Middle Ages and showed no sign of declining when the Reformation and Counter-Reformation came in the sixteenth century. Some of the most sumptuously illustrated books were made for wealthy lay patrons, including royalty. They were worldly status symbols although, as comparatively small and private objects, an example of inconspicuous consumption. The motive that inspired people to commission a book either for personal use or for donation to a church was devotion to God.

Satan tempts Christ to make a leap of faith from the top of the Temple in Jerusalem, a scene from St Matthews Gospel illuminated with gold leaf in East Anglia c.1190.

In classical antiquity a text was a script for reading aloud, and consumers of literature expected to hear the words as much as see them on the page. The emergence of illuminated manuscripts charts a transition to silent, private reading. When they are depicted in art, classical authors are shown dictating to scribes, but in the Christian era the authors of the Gospels are shown writing their own texts. Writing became a sacred act. The work of copying text was a labour of love, but it was also long and laborious. With a sigh of relief an East Anglian scribe added at the end of a book of psalms, The book is finished. Praise and glory be to Christ. Amen. No less a sacred act was the work of the illuminator. The illustrations in a medieval book are not merely ornament. They amplify the holiness of the text and transform the word of God into an object of beauty. Every beautiful medieval illuminated manuscript was made to glorify God.

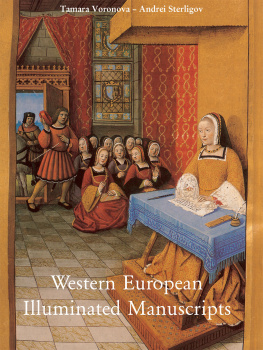

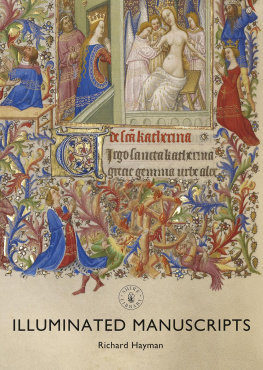

St Jerome is depicted in his study in a fifteenth-century Book of Hours by a French artist possibly working in London. Jeromes translation of the Bible, known as the Vulgate, was used throughout western Christendom in the Middle Ages.

The book has always been central to Christian worship and teaching, and the book form itself is closely associated with the rise of Christianity. Greek and Roman literature was written on one side of a roll of papyrus, but in the early Christian world it was superseded by the book, composed of many leaves bound together and written on both sides, known as a codex (plural codices). Codices illustrated with narrative scenes began to supersede the papyrus roll in the eastern Mediterranean by the fifth century. St Jerome (c.347420), scholar and translator who lived much of his life in Syria and Constantinople, was critical of the new fashion for luxurious decoration of books, suggesting that it was a new phenomenon in his day. Ironically, many of the most beautiful books produced in the Middle Ages were of the Latin Bible, in a version known as the Vulgate which was translated by Jerome himself.

BOOK PRODUCTION

I lluminated manuscripts were produced on parchment, also known as vellum. Parchment was much more suitable than papyrus for a book in which pages were turned and, as it was made from the skins of animals, was more readily available across most of Europe than papyrus, which was invented by the Egyptians and was made from the stem of the papyrus plant found along the course of the Nile. Parchment was made from the skins of sheep or calves, so could never be mass-produced like paper. The skins were soaked, bathed in a lime solution, scraped, rinsed, stretched and cleaned with pumice and water, leaving a smooth surface ideal for the scribe and illuminator.

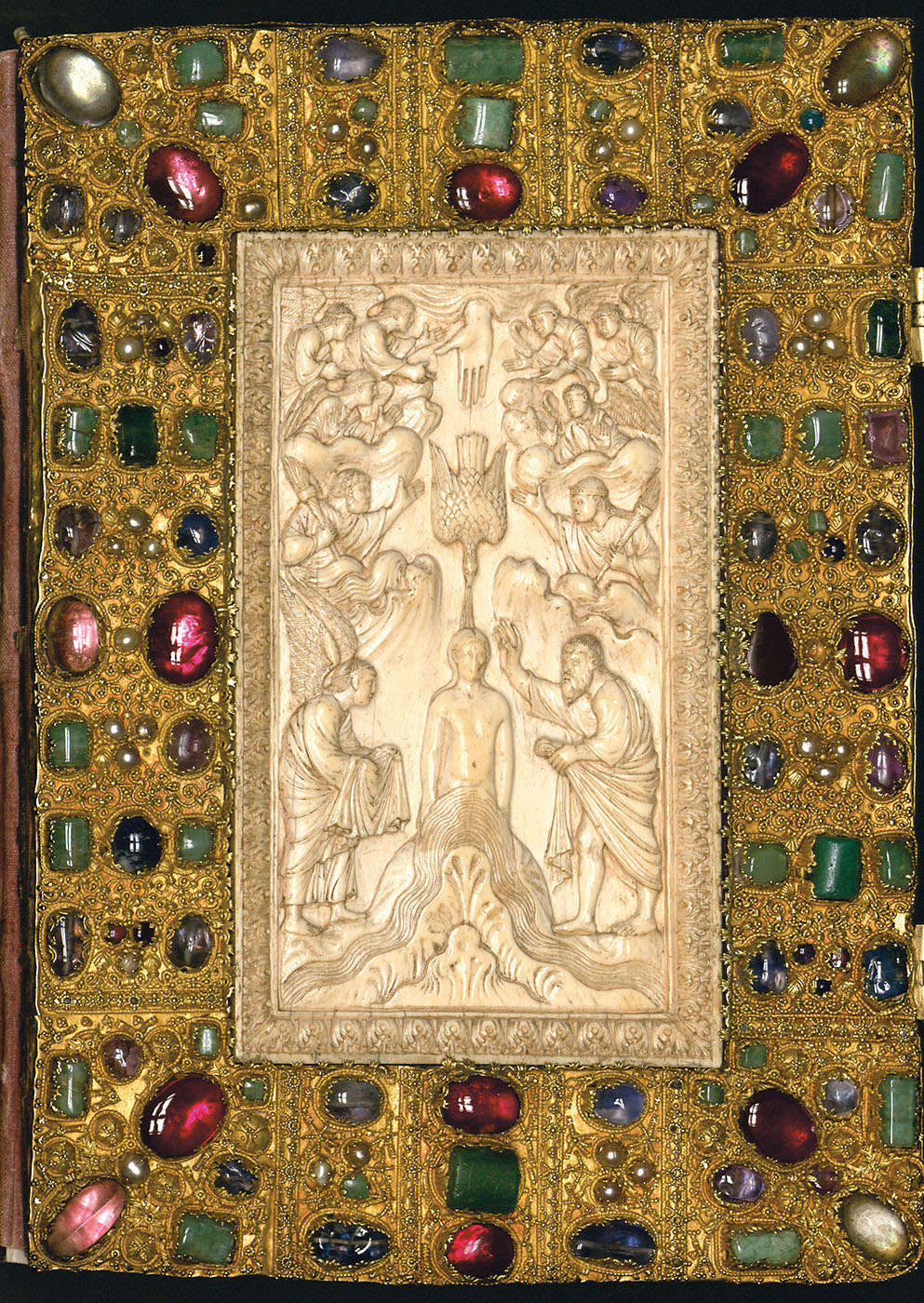

The jewelled binding with pearls and precious stones set in a gold plate with filigree decoration, and including an inset ivory panel showing the baptism of Christ, shows the opulence of the most luxurious ninth-century Gospel Books made in Germany.

Parchment naturally forms oblong pieces and it has dictated the standard shape of the book ever since. Books, however, varied in size. For a large volume single pieces of vellum were folded in half and usually four folded pieces were placed inside each other to form eight leaves (the equivalent of sixteen pages), which were known as a quire or gathering. For smaller books a single piece of vellum could be folded twice and trimmed, to produce four leaves, or folded again and trimmed to produce a quire of eight leaves. A book was composed of a series of quires bound in sequence. Few medieval books had numbered pages and the convention is to count leaves (known as folios) rather than pages, each of which has a front (recto) and back (verso).