Christopher De Hamel

MEETINGS WITH REMARKABLE MANUSCRIPTS

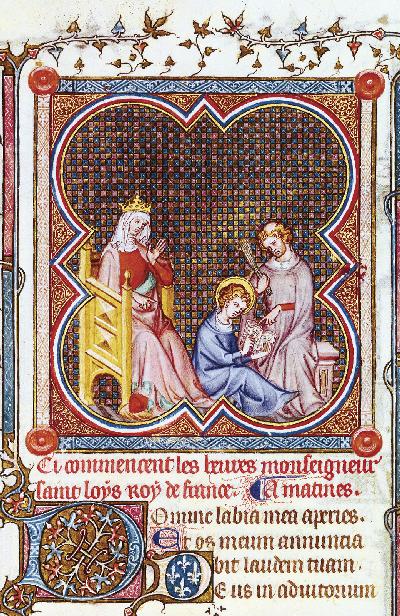

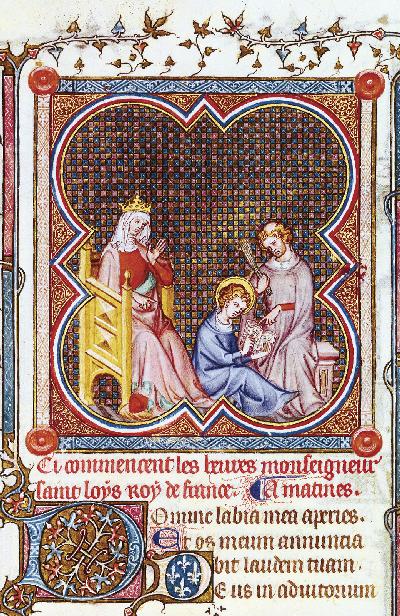

Saint Louis as a child being taught to read under the direction of his mother Blanche of Castile, as depicted in the Hours of Jeanne de Navarre, Paris, c. 1334. (See )

Introduction

This is a book about visiting important medieval manuscripts and what they tell us and why they matter. As first envisaged, it was to be called Interviews With Manuscripts, and indeed the chapters are not unlike a series of celebrity interviews. Actual interviews traditional published interviews with well-known people usually set the scene and describe the circumstances of how the encounters came to happen at all. They generally attempt to evoke something of the experience of meeting and interacting with the interviewees. You will already have had information in advance, of course, but what are the people like in reality, when they finally come to the door, shake your hand and usher you to a seat? The accounts may say something of their physical presence and perhaps their clothes, demeanour and style of conversation. We may all pretend that a well-known person is really no different from any other human being, but there is an undeniable thrill in actually meeting and talking to someone of world stature. Is he or she, in fact, charismatically impressive, or (as sometimes) rather disappointing? You might seek to discover how people became famous and whether their reputations are deserved. Listen to them and let them speak. A good interviewer may be able to elicit secrets which were entirely unknown and which the famous person had meant to keep quiet. There is even a certain voyeurism for the reader in eavesdropping as these intimate confessions are teased out.

The most celebrated illuminated manuscripts in the world are, to most of us, as inaccessible in reality as very famous people. To a large extent, anyone with stamina and a travel budget can get to see many of the great paintings and architectural monuments, and may stand today in the presence of the Great Wall of China or Botticellis Birth of Venus. But try just try to have the Book of Kells removed from its glass case in Dublin so that you can turn the pages. It wont happen. The majority of the greatest medieval manuscripts are now almost never on public exhibition at all, even in darkened display cases, and if they are, you can see only a single opening. They are too fragile and too precious. It is easier to meet the Pope or the President of the United States than it is to touch the Trs Riches Heures of the Duc de Berry. Access gets harder, year by year. The idea of this book, then, is to invite the reader to accompany the author on a private journey to see, handle and interview some of the finest illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages.

Palaeographers, the general term for those of us who study old manuscripts, become accustomed to working in the reading-rooms of rare-book libraries, but these are sanctuaries as out of bounds to the general public as the tomb of the Prophet in Medina would be to me. Modern national libraries are among the costliest public buildings ever constructed, but few people actually penetrate as far as the exclusive tables set aside for consultation of the most valuable books of all. Some settings for studying manuscripts are stately and intimidating, and others are endearingly informal. Access is a secret of initiates, and formulas for admission and the handling of manuscripts vary hugely from one repository to another. This is an aspect of the history of scholarship often entirely neglected. The supreme illuminated books of the Middle Ages are cornerstones of our culture, but hardly anyone bothers to document their habitat.

Some of these great manuscripts may be known from facsimiles or from digitized images available on-line, as accessible and as familiar as authorized biographies of well-known people, but no copy is the same as an original. The experience of encounter is entirely different. Facsimiles are rootless and untied to any place. No one can properly know or write about a manuscript without having seen it and held it in the hands. No photographic reproduction yet invented has the weight, texture, uneven surface, indented ruling, thickness, smell, the tactile quality and patina of time of an actual medieval book, and nothing can compare with the thrill of excitement when a supremely famous manuscript itself is finally laid on the table in front of you. You do not merely see it, as under glass, but really get to touch it and peer into its crevices. There will always be details which no one has seen before. You will make discoveries every time. Unnoticed evidence may be wrested from signs of manufacture, erasures, scratches, overpainting, offsets, patches, sewing-holes, bindings, and nuances of colour and texture, all entirely invisible in any reproduction. The questions manuscripts can answer face-to-face are sometimes unexpected, both about themselves and about the times in which they were made. There are new observations and hypotheses in every chapter here, elicited by nothing cleverer than engaging the originals. Look closely. Use a magnifying glass, if you like. Sit back: turn the pages and listen quietly to what the books tell us. Let them talk. Apart from anything else, this is enormously enjoyable and interesting. Medieval manuscripts have biographies. They have all survived through the centuries, interacting with successive owners and ages, neglected or admired, right into our own times. We will disentangle provenances which were entirely unknown. Sometimes these histories are very dramatic, as books take their place in European affairs at the highest level, from the bed chambers of medieval saints and kings to the secret hiding-places of Nazi Germany. Habent sua fata libelli. Some manuscripts have hardly stirred from their original shelves since the day they were completed; there are others which have zig-zagged across the known world in wooden chests or saddle bags swaying on the backs of horses or over the oceans in little sailing ships or as aircraft freight, for books are very portable. Many have at some time passed through commerce and the auction rooms, and the prices attached to them as they transited are a part of the changing history of taste and fashion. The life of every manuscript, like that of every person, is different, and all have stories to divulge.

A dozen manuscripts have been selected for interview here. No one really knows how many medieval manuscripts survive throughout the world maybe a million, perhaps more and the choice was very wide indeed. They are all potentially fascinating and even the plainest and scruffiest of those manuscripts would have offered up enough material to fill a chapter of this book, but it might have made a less glamorous experience for the reader. We are going to be moving in grand company. As you sit in the reading-room of a library turning the pages of some dazzlingly illuminated volume, you can sense a certain respect from your fellow students on neighbouring tables consulting more modest books or archives, and I hope to share a flavour of that quiet satisfaction of associating with celebrated manuscripts, which for a short while are to become our intimate companions. Join me in a bit of self-indulgent namedropping. Among these titans I have tried to choose a representative range of different kinds of medieval book, not all Gospels and Books of Hours but also texts of astronomy, biblical commentaries, music, literature and Renaissance politics. We could also have opted for liturgy, medicine, law, history, romance, heraldry, philosophy, travel, or many other subjects widely covered in manuscripts of the Middle Ages. I have singled out volumes which seemed to me characteristic of each century, from the sixth to the sixteenth. They all tell us something about their times and the societies which made them.