All rights reserved. No part of this may be reproduced or adapted without the permissison of the copyright holder, throughout the world.

Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

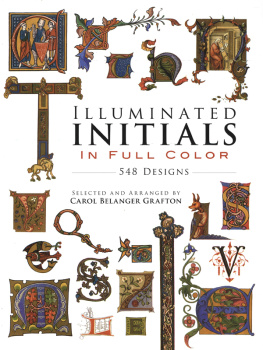

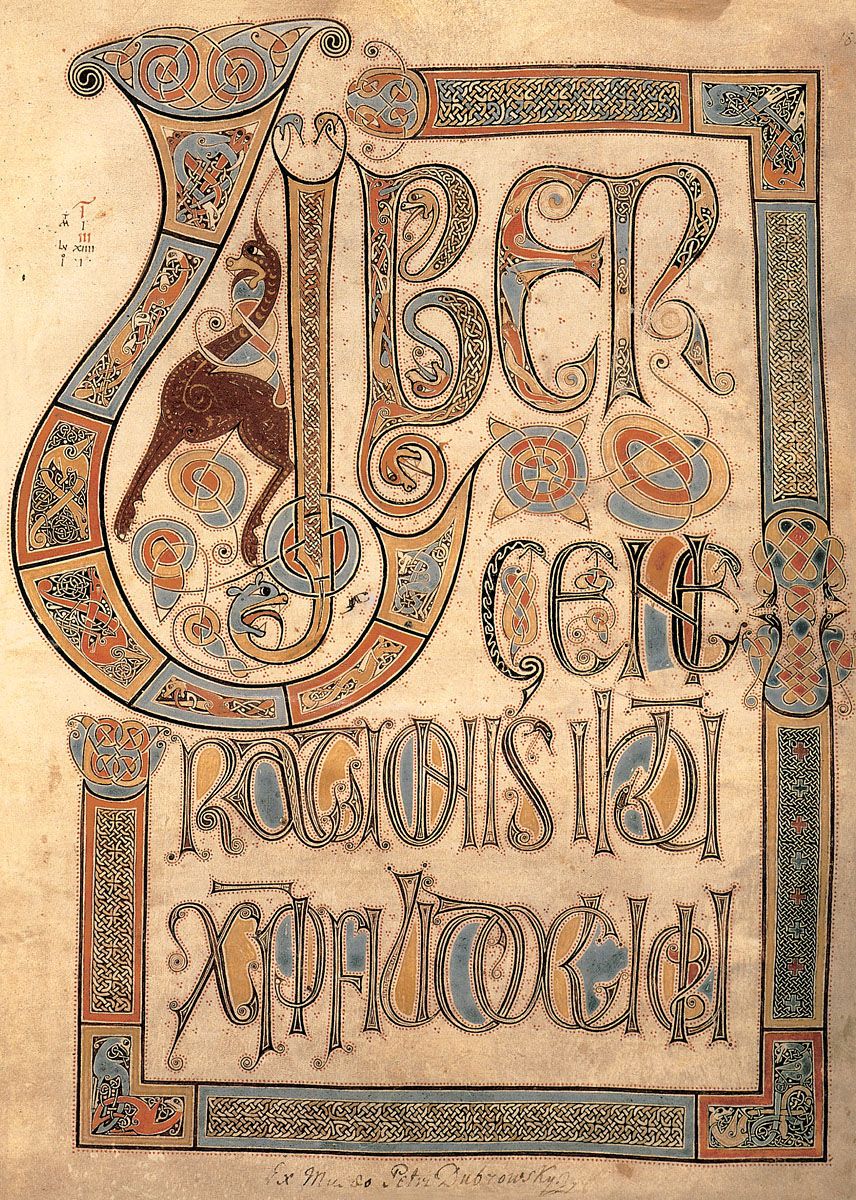

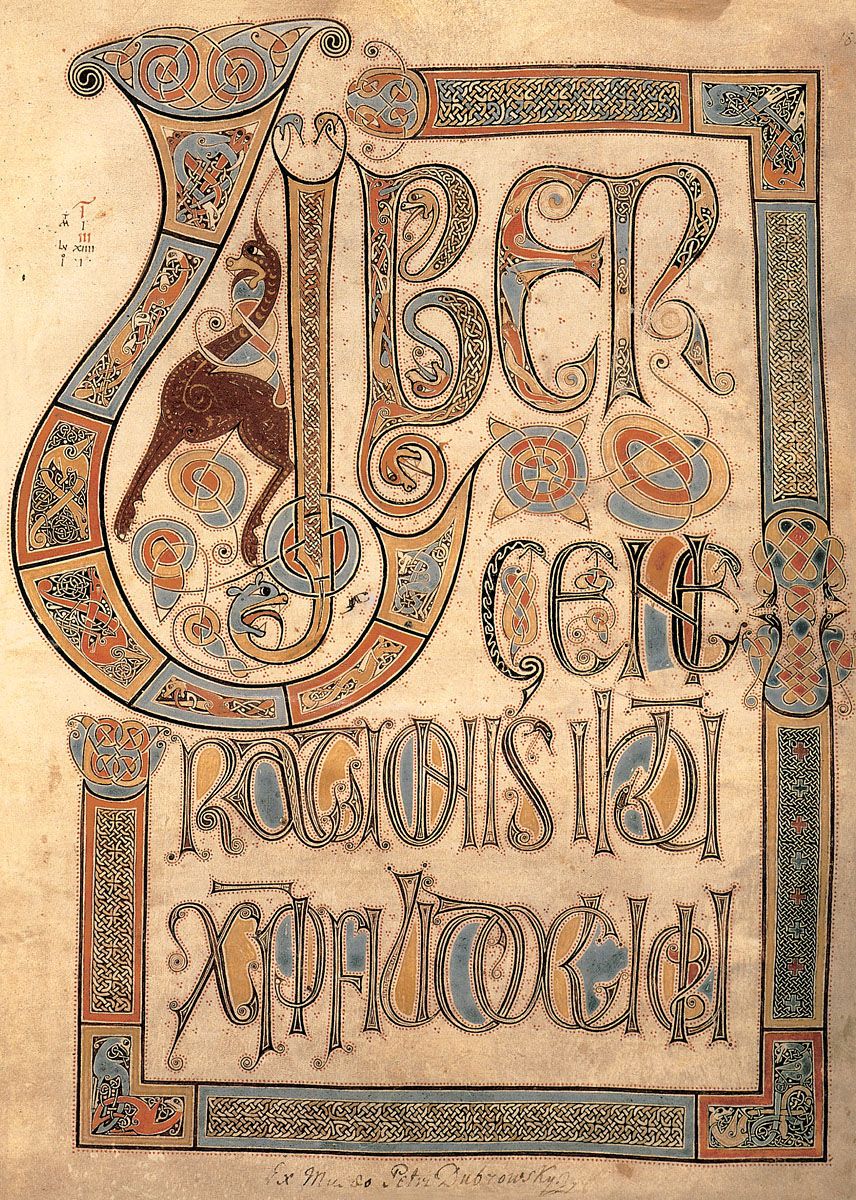

F. 18. Page of Initials of the Gospels to St Matthew (Liber generationis) Evangelistery. Northumbria (?) End of 13 th century.

INTRODUCTION

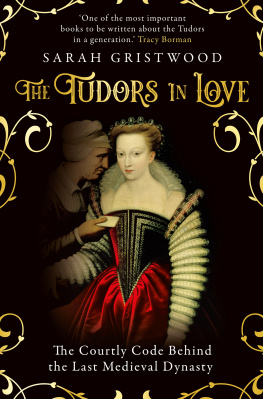

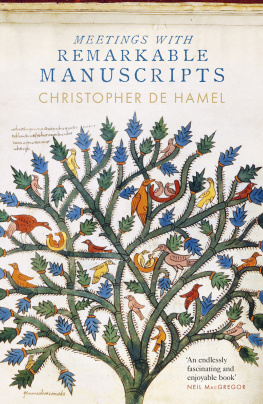

Anyone fortunate enough to have actually held a medieval manuscript in his hands must have felt excited at this immediate contact with the past. Both famous and unknown authors wrote philosophical, natural scientific and theological treatises, romances about knights and courtly love; humanists and theologists translated and commented upon the classical literature of antiquity; travellers wrote descriptions of their incredible journeys; and ascetic chroniclers recorded and kept alive the historic events of their times for future generations. One can imagine a scribe constantly at work in a shop in some quiet narrow street of a medieval town, or a monk diligently reproducing the words of Holy Writ over and over again in a monastery scriptorium.

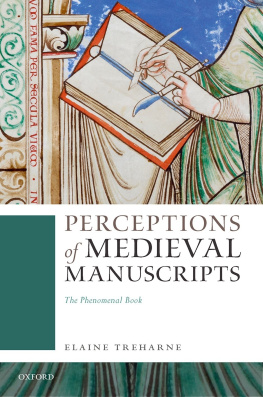

The more elaborate and complicated the history behind a medieval manuscript and the more it was read, cherished and admired, the greater its charm. Often this special charm is enhanced by the joy of seeing a highly professional, exquisite example of the art of book illumination. The emotional impact of each of its components is increased by the alliance of the text, the specific technique of producing medieval manuscripts and a refined design.

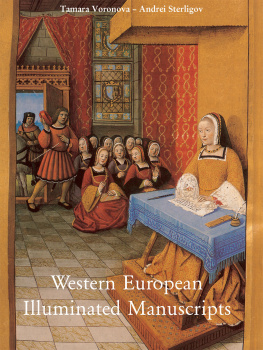

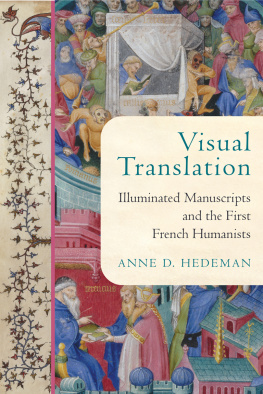

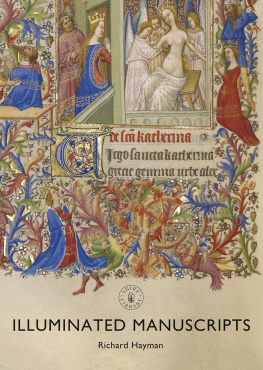

Skilled artists turned the heavy volumes of chronicles and Bibles, works by ancient and medieval authors and small exquisite Books of Hours into tiny picture galleries hidden between the bindings. Fortunately, miniatures by Byzantine, Southern Slavic, Old Russian, Armenian, Georgian, Persian and Indian masters, which play an important role in the history of world art, have come down to us. This book is devoted to miniatures from medieval Western European manuscripts, whose features and importance will be further described.

Even in those rare cases when a building decorated with frescoes has survived without having been damaged and without having had its murals painted over in the course of successive ages at the whim of changing tastes, fluctuating temperatures and the effects of the atmosphere have substantially altered the original colour of the works.

The fate of easel paintings is seldom much better: their colours have changed as a result of the effects of light and air, their paint cracks and chips off or they have been painted over or renewed. The colours of gorgeous tapestries have also faded, while fragile stained-glass windows have seldom survived historical cataclysms. Only miniatures, protected to a large extent from damp, air, light and dust between the covers of the book, convey the true, unchanged colours of medieval painting.

The skill and care with which the miniatures were painted also explains why they have remained in such good condition. The monks working in scriptoria were inspired with a profound veneration for the text with which they worked. Secular masters were motivated by the prestige of their workshop, further orders depending on the perfection of their technique. Commissioned by the aristocracy, the clergy, or the growing financial and mercantile bourgeoisie, illuminated manuscripts became luxury items whose skilful execution and expensive materials made them as valuable as precious pieces of jewellery.

Illuminated manuscripts have also been favoured because they have always been collectors items which, before the foundation of public museums, were usually lovingly kept in libraries. But it is more than just their good fortune that determines the significance of the miniatures. In recent years more extensive and profound study of illuminated manuscripts has shown that they have such an important place in the arts that it would be impossible to conceive the artistic culture of the past without them.

Illuminated manuscripts were, as has been said, mainly intended for the social elite. Illiteracy and the tremendous cost of handwritten books limited the number of people to whom the artist could address himself. This exclusive character of illuminated manuscripts, however, did not lead them to become hackneyed. When manuscript production shifted in the thirteenth century from monasteries to city workshops, it was there that the artistic discoveries having an impact on art in general appeared. Scholars today often call illumination a research field for painting and a laboratory of new inventions. The new artistic idiom, that is the treatment of space, the rendering of mass, volume and movement, etc., was largely worked out in illuminators ateliers. The illustrative function of miniatures accounts for their being more narrative and detailed, and it made their authors attempt not just a representation of space, but one that would show the duration of time as well. Early French painting, the French art expert Greta Ring wrote, is bolder on parchment than on panel.

Miniatures also played a significant role in the appearance of new genres, primarily landscape and portrait painting. Given the freedom in the treatment of subject-matter and the considerably broader variety of themes used in illumination compared to easel painting, this was not at all surprising. One cannot help admiring the boldness, creative energy and ingenuity of miniaturists who propelled art forward in spite of the rigid limitations of tradition. Gradually they introduced new elements in drawing, colour scheme and composition, widening the scope of scenes, objects and decorative motifs by employing their observations from life more and more.

When assessing the role of illuminated manuscripts in the history of art, it should not be forgotten that an illustrated book, like many works of applied art, could be easily carried from place to place: upon marriage, princesses took with them the works of their countrys most famous miniaturists; men of noble birth who settled in to new lands received them by inheritance; they were given as trophies to a victor. Illuminated manuscripts circulated all over Europe, introducing new tastes, ideas and styles. There is no doubt that the influence of Parisian art on many countries in the second half of the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries can be explained to a great extent by the spread of illuminated manuscripts.

Strong and mutually enriching ties can be traced not only with easel painting, but with sculpture as well. In developing the sculptural decorative scheme of Romanesque and Gothic cathedrals, manuscripts served as a source of themes, images and iconography. Representations found in manuscripts were used by enamellers, ivory carvers, weavers, stained-glass window designers and even architects.

But the opposite trend also existed, sometimes very powerfully, with illumination drawing on the other plastic arts. Here too the study of manuscripts is very helpful in understanding the culture of the past. Up until the middle of the fifteenth century French miniaturists, including Jean Fouquet, were inspired by the splendid sculptures of High Gothic art. Having been strongly influenced by stained glass in the thirteenth century and by Italian frescoes in the fourteenth, in the fifteenth century illuminators incorporated the discoveries of Netherlandish painters, Italian architects and other contemporary sculptors and artists into their works. Significantly, illumination played an independent and important role in the complex and fruitful interaction of different artistic schools, forms and genres.