Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

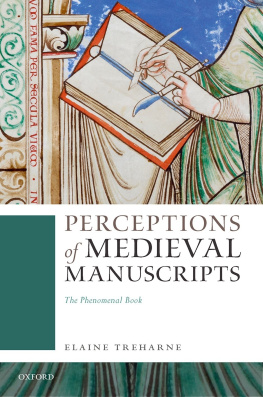

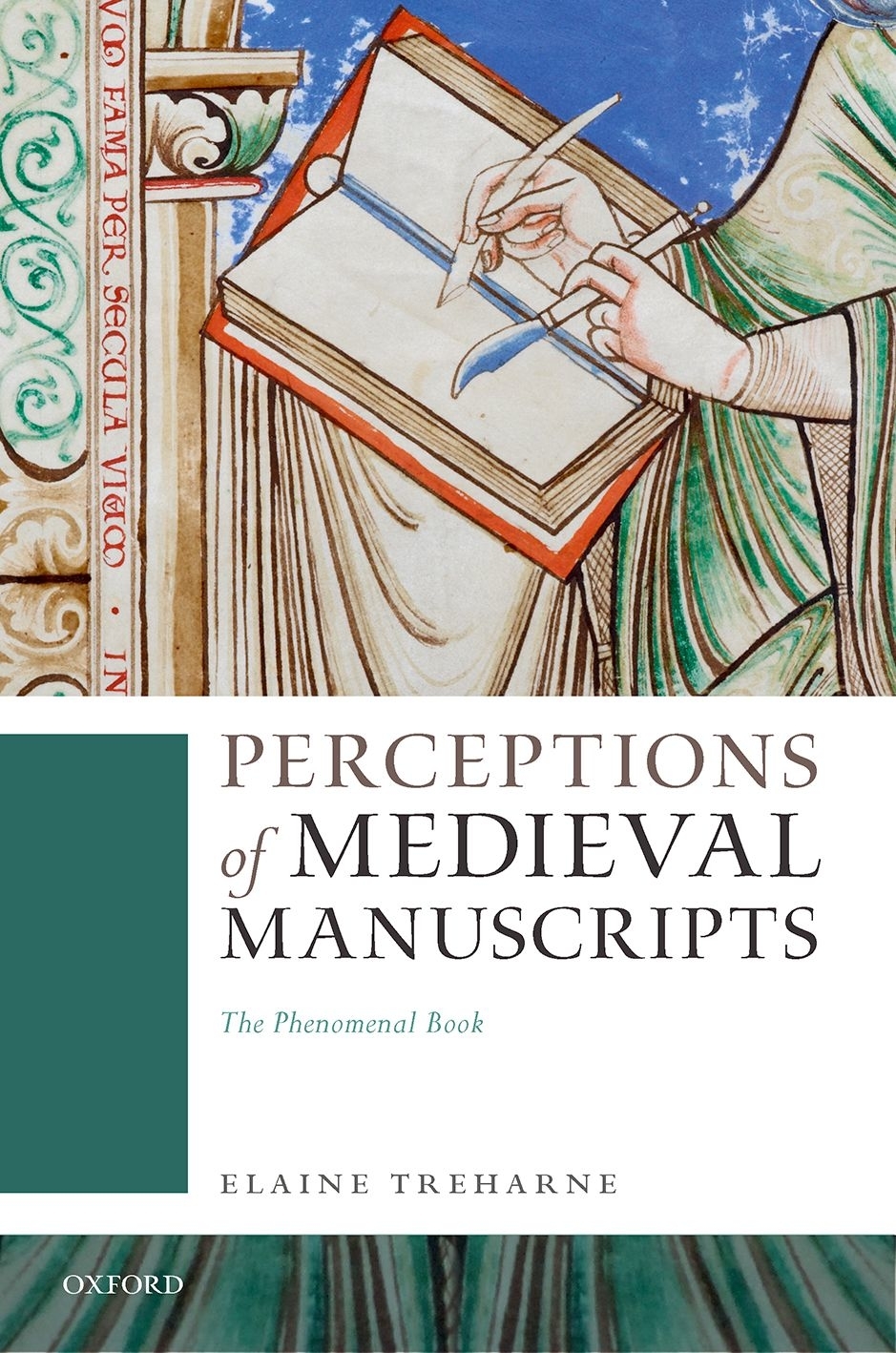

Elaine Treharne 2021

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2021

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021938591

ISBN 9780192843814

ebook ISBN 9780192657534

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780192843814.001.0001

Printed and bound by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Preface

On 26 March 2015, Richard III was reinterred at Leicester Cathedral. His broken bones, discovered underneath a carpark at Greyfriars in Leicester, were ceremoniously laid to rest in a lead-lined coffin. The archbishop of Canterbury, pre-eminent prelate of a church that did not exist when Richard III was on the throne in the 1480s, led the service. Benedict Cumberbatch, the dead kings second cousin sixteen times removed, read the moving poem, Richard, written for the occasion by Poet Laureate Carol Anne Duffy. In that poem, Duffy imagines the voice of the king beseeching the modern era: Grant me the carving of my name. This desire to be inscribed and memorialized, while fictional in this poem, is real enough for sentient beings, who wish their lives to be remembered if not by deeds or offspring then through their name. The focus on being named and situated through a name-made-permanent is allied in its emphasis on writing by another fulcral event in Leicester Cathedral on 26 March; namely, the loan of Richard IIIs own personal prayer-book for the occasion to reunite long-dead monarch and long-dormant manuscript. As scholar Lisa Fagin Davis tweeted on that day: Very moving to see RIII reunited with his Book of Hours. Every medieval manuscript was once someones book.

Perceptions of Medieval Manuscripts explores the implications of this simple truth: that every manuscript was once in the world as someones book, and was often many peoples book in the years between its creation and now. It was a thing to be read, certainly, but also a thing written, sourced, shaped, and tooled by its creators; held, admired, perhaps caressed, neglected, or spurned by successive owners and handlers. Perceptions of Medieval Manuscripts considers how the medieval manuscript was and is perceived; its modes and meanings of production and reception in the long medieval period from the end of the sixth century through to the fifteenth century and on into the present day. Accepting the basic phenomenological premise that the book is a whole textual object, albeit one subject to shape-shifting, adaptation, and transformation, this study investigates the form and function of the handmade book, principally using British examples. This study demonstrates that an approach emphasizing dynamic architextuality allows us to re-see the book in its wholeness and to better understand the significances of this most unique of things.

.

Acknowledgements

As I finish this book, which has been too long in the making, most of the world is struggling to function during the COVID-19 pandemic. I am sheltering in place, wondering if this kind of activitywriting books on medieval manuscriptsis really how I should spend my energy. Medievalist Andrew Prescott reminded me that it is precisely in these crises that we turn to literature, art, music, poetry, the spirit. He is right. And medieval manuscripts are the containersthe vesselsof the human spirit, so perhaps this will have been time well spent.

This book began as an investigation into the types of interactions made by users of medieval books, a study which itself emerged out of years of work on medieval glosses within manuscripts and on twelfth-century responses to pre-Conquest English texts. It has grown into something more extensive, now being an examination of attitudes towards medieval books mostly produced in the Western Christian tradition, and the ways in which these books appear to have been regarded. I have discarded as many pages of research as I have included, so this is a highly selective study in the end. From a thorough analysis of images of manuscripts within manuscripts, together with a detailed study of marginalia, annotation, and glossing, this book offers the first holistic account of the medieval book in the physical worldas icon, artefact, commodity, and as object of then-contemporary research. The findings open up new avenues for further work, and for a more comprehensive understanding of the significant role played by the medieval book from c.600 to the present day.

I am grateful to Jacqueline Norton and Aimee Wright, and the two Readers at Oxford University Press, whose generous comments, helpful criticisms, and observant corrections helped shape the final book. In the course of this work I owe sincere thanks to my University of Manchester magistri: Richard Hogg, Gale Owen-Crocker, Donald Scragg, and the most brilliant of palaeographers, Alexander R. Rumble. Subsequently, my research has been facilitated by funding from Stanford University, particularly associated with the Roberta Bowman Denning Endowed Chair that I hold; and by a small grant from Florida State University which paid for research assistance from William Green and Kate Lechler, whom I thank. For their knowledge, kindness, and warm welcomes, thanks to Gill Canell at the Parker Library in Cambridge, Sandy Paul and Steven Archer at Trinity College, Cambridge, and Suzanne Paul at Cambridge University Library, as well as the librarians at the British Library, and those then at Florida State, particularly Bill Modrow, Ben Yadon, and Jane Pinzino. Celena Allen, Laura Ashe, Tom Bredehoft, Jayne Carroll, Patrick Conner, Anne Marie DArcy, Nick Doane, Richard Emmerson, Toni Healey, Chris Jones (St Andrews), Beatrice Kitzinger, Christina Lee, Roy Liuzza, Katie Lowe, Diane Watt, and Eric Weiskott have played important roles in my thinking. I am grateful to my students at Stanford, especially Jeanie Abbott, Max Ashton, Lorna Corbetta, Ben Diego, Liz Fischer, HB Klein, Antonio Lenzo, Kim Ngo, Jon Quick, Astrid Smith, and Clare Tandy. It was a privilege to work alongside Georgia Henley and Bridget Whearty when they were postdoctoral fellows here at Stanford. The Medieval Writers Workshop was such a helpful venue to present the general thesis of this work; thank you to Tiffany Beechy, Jacqueline Fay, Stacy Klein, Scott Kleinman, Heather Maring, and Britt Mize. Colleagues at the Extreme Materiality Workshop at the University of Iowa years ago were excellent companions for weeks of practical and theoretical discussion: thank you so much to Jonathan Wilcox, Tim Barrett, Jennifer Borland, Patrick Conner, Gary Frost, Karen Gorst, Matt Hussey, Cheryl Jacobsen, Karen Jolly, Vickie Larsen, Jesse Meyer, and Martha Rust. Students and faculty who heard various lectures about my research have offered substantive feedback for the last decade; these include medievalists at the universities of West Virginia, Wisconsin Madison, Caltech, De Montfort Leicester, Boston College, Sewanee, Yale, Texas Austin, Texas A&M, Fort Wayne, Toledo, Leiden, Washington, George Washington University, Colorado Boulder, Berkeley, Oxford, Tennessee Knoxville, Lincoln, Minnesota, Harvard, Edinburgh, Glasgow, St Andrews and the University of Iowa. At Stanford, I am indebted to Mark Algee-Hewitt, Giovanna Ceserani, Rowan Dorin, Ron Egan, Marisa Galvez, Ivan Lupic, Bissera Pentcheva, Stephen Orgel, Richard Saller, and Alice Staveley. Stanford University Libraries is comprised of wonderful colleagues for whom I am grateful, including Nicole Coleman, John Mustain, Tim Noakes, Kathleen Smith, Roberto Trujillo, and Rebecca Wingfield. Particular collaborators and friends over the years, Ruth Ahnert, Benjamin Albritton, Mateusz Fafinski, Jill Frederick, Catherine Karkov, Bill Stoneman, and Kathryn Starkey, inspire me with their exemplary scholarship and collegiality; Matt Aiello has been as significant a teacher to me as he has been a student; and Mary Swan was a singular friend and co-worker, from whom I did and will continue to immeasurably benefit.