IMAGES

of America

1968 FARMINGTON

MINE DISASTER

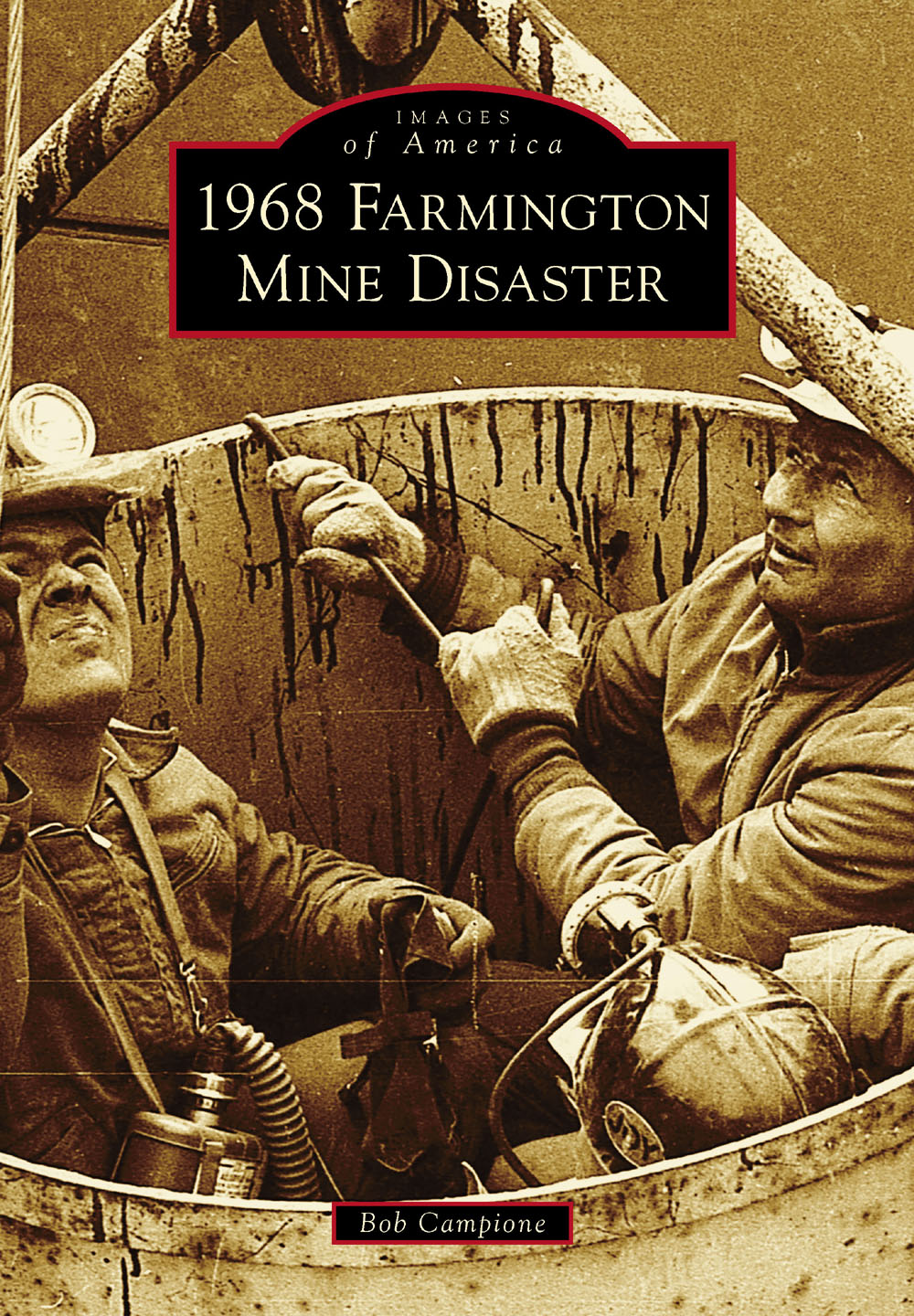

ON THE COVER: The last three men come out from the depths of the Farmington Mine on the morning of November 20, 1968. They were rescued using a construction crane and a bucket from a nearby construction project. All three of the men in the bucket were among the men who were working the midnight cateye shift, and they were the last three working in the mine that night to come out alive. In the bucket are Gary Martin (left), Bud Hillberry (right), and Charlie Crim (back to camera). (Photograph by Bob Campione.)

IMAGES

of America

1968 FARMINGTON

MINE DISASTER

Bob Campione

Copyright 2016 by Bob Campione

ISBN 978-1-4671-2378-5

Ebook ISBN 9781439657935

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016947309

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

This book is dedicated to the 78 men who perished in the Farmington No. 9 coal mine in November 1968 and all the other miners who gave their lives to dig the black rock from the earth. Without them, our nation would not have electricity to power our homes or our industries. Coal plays a vital role in the production of steel, and coal by-products are used in many pharmaceuticals, plastics, and other consumer goods. The families of the coal miner also play a tremendous part in supporting the men who mine the coal. Family members always lived in fear of their loved one someday not coming home from work. Many times, mothers and wives would hate to answer the phone near the end of their miners shift for fear it was going to be bad news.

A personal dedication goes to my father, Angelo Campione, for his devotion to his family and working 40 years underground to support us. He never complained about his work and made sure we had a good home and an opportunity of getting an education so my brother and I would not have to endure working in the coal industry. His life was shortened likely from the results of mining underground, as he died at age 68, only four years after he retired.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book is a product of many sources of information, starting with the newspaper accounts written by one of the most competent editors of the time, William Dent Bill Evans of the Fairmont Times. The depth of his knowledge on coal mining was a major factor in getting all the facts correct in his writing about this disaster.

Many thanks also go to Bonnie E. Stewart for her investigative reporting and publishing of her book No.9The 1968 Farmington Mine Disaster. She uncovered many facts that were buried in files for years, and she researched many areas that were locked away from the public.

Thanks go to all who responded on social media with help identifying many of the faces in the photographs: Anthony Pulice, Janet Lieving, Bill Rice, Ron Crites, and Olive Marie Utt.

Many thanks go to my wife, Andrea Campione, for her encouragement and proofreading skills. Without her, I am not sure it would have been completed.

Unless otherwise noted, all images appear courtesy of the authors collection.

INTRODUCTION

The morning of November 20, 1968, started with a phone call around 6:30 a.m. at the Campione household. Sarah Campione answered the phone and was asked by the editor of the Fairmont Times, Bill Evans, if she would get her son Bob to come to the phone. Bob Campione, age 20, had been the photographer for the Times during high school and college up until his final semester, but he had to resign his full-time position while taking education classes at Fairmont State College that semester. The young photographer came to the phone, and Evans explained that there had been an explosion at the Farmington No. 9 mine and was requesting he come pick him up and go with him to photograph the incident. Campione requested he call his replacement because of his class schedule, but Evans insisted he needed him to go because of his experience and the magnitude of the situation. At this time, Campione was not officially employed by the newspaper; he was considered to be a freelance photographer and would be paid for any photographs used in publication.

The young photographer dressed and picked up Evans at his home on the other side of town, and the two traveled to the mine. It was a cool November morning, and as they approached the small rural town of Farmington, it was apparent by the dark haze in the sky something evil had happened. They had to drive through the small community of Farmington on their way to meet up with federal and state mine inspectors at the mines main tipple. The tipple was located a few miles north of the small community, and during that short drive to the tipple, no words were spoken in the car. The uncertainty of what was around the next turn caused ones mind to speculate various scenarios of what might be encountered.

As they rounded the final turn with the Farmington No. 9 (Consolidation Coal Company, also known as Consol) in sight, nothing seemed to be amiss here, to their surprise. As they pulled into the parking lot of the Champion company store, directly across the road from the main tipple, there were already several other cars in the lot. Some of them had federal license plates, and others had official state tags. When Campione and Evans got out of the vehicle, they were greeted by a couple of the men dressed in mining clothes. These were the federal mine inspectors that had called Bill Evans in the early hours of the morning to inform him of the incident. Evans had become somewhat of an authority in covering mining accidents and explosions, so the inspectors knew he would be able to report clearly and factually the events about to unfold.

After a briefing from the mining inspectors, Campione got back in his car and began the drive to the Llewellyn portal. The drive seemed to take forever as thoughts raced through his mind. He could see in the distance a black column of smoke and continued his drive in that direction. As he went up the small, twisting country road, the column of smoke became more intense, and rounding the final curve, he saw the smoke-engulfed elevator structure and bathhouse where the miners would dress for work and shower after work before going home. Getting out of his car, Campione could smell the pungent odors being produced from the fire deep underground. He recognized the man trip elevator structure because as a small child he would go with his father, a coal miner, to the Grant Town mine where his father worked, to pick up his paycheck.

Climbing up a small embankment across the road from the structure, Campione leaned against a large oak tree and collected his thoughts. Checking the settings on his camera and using the tree as a support, he shot his first picture of the day. While he was standing there and looking at all the cars in the parking lot, one vehicle caught his eye. He recognized the car belonging to a friends father. He had been in this car many times while riding to East Fairmont High School with him and his son. Suddenly, the magnitude of the situation took on a more personal impact.

As Campione was driving back to the main tipple to reconnect with Evans, his thoughts raced back to a time when he got to the newspaper office and Evans told him they needed to go report on a mine incident. Evans would not tell him which mine they were going to, but only to drive in the direction south of Fairmont. There were several mines in that direction Campione knew of, and as they approached Barrickville, Evans instructed him to turn in that direction. Making the turn toward Barrickville, Campione asked again which mine they were going to, and Evans finally told him it was Grant Town. That time of day, around 3:30 p.m., Campiones dad would be in the mine. The trip to the bathhouse suddenly seemed like an eternity. Reaching the parking lot of the mine, the two men went into the area where the miners would enter the elevator leading into the mine. The young photographer knew to check the board near the entry to the elevator to see if his dads check tag was on the In side or the Out side of the board. His fathers tag number 703 was on the In side of the board, which meant his father was still in the mine. Young Campione stood there frozen and afraid to ask any questions, fearing the worst. Suddenly, a miner still in his dirty mine clothes approached and asked him, Are you Angelos son?to which he replied yes. The miner informed him that his dad was on the next trip of miners coming out of the mine and that everyone was safe. This was a huge relief to the young man as he waited to see the man trip elevator door open and see his dads dirty face. His fathers check tag still sits on Bob Campiones dresser to this day, along with a pocket watch, to remind him of his fathers life as a miner.

Next page