COAL CULTURES

PHOTOGRAPHY, PLACE, ENVIRONMENT

Series Editors: Liz Wells

Photography, Place, Environment publishes original scholarship and critical thinking exploring ways in which photography contributes to, or challenges, narratives relating to geography, environment, landscape and place, historically and now.

International in scope, and innovatory in placing imagery as both the object and the method of enquiry, the series includes single-authored and edited volumes by new scholars as well as established names in the field. By critiquing relationships between land, aesthetics, culture and photography, the books in this series also foster debates on photographic methodologies, theory and practices.

Coal Cultures: Picturing Mining Landscapes and Communities, Derrick Price

Renegotiating Landscapes: Art, Photography and Politics in Postcolonial Documentary Practices, Nicola Brandt

Photography and Environmental Activism, Conohar Scott

COAL CULTURES

Picturing Mining Landscapes

and Communities

Derrick Price

I am indebted to Liz Wells for making this book possible. Her incisive reading of the text and her critical responses to it were very valuable. More than this, I need to thank her for the fact that our discussions and debates over the years have helped to shape my view of photography and its place in contemporary culture. The task of sourcing photographs was made pleasurable by working with Sophie Tann of Bloomsbury Academic. She remained positive and constantly helpful even when I was despondent and finding the whole thing a tedious chore. Paul Cabuts was an insightful reader of the manuscript and I really appreciated and benefited from both his encouragement and his criticisms. Richard Dyer very kindly gave me notes he had made on mining in the context of the miners strike of 1985. Marc Arkless of Ffotogallery patiently guided me through the archive of The Valleys Project, and I am very grateful for his help. My greatest debt is, as always, to my wife, Helen Taylor. Over the years she has driven me through the valleys of South Wales, strapped on a hard hat to travel through heritage mines, and responded to countless stories of the industrial past. Her support for this project was crucial to me, as are the long conversations, jokes, rows and exchanges that are at the heart of our life together.

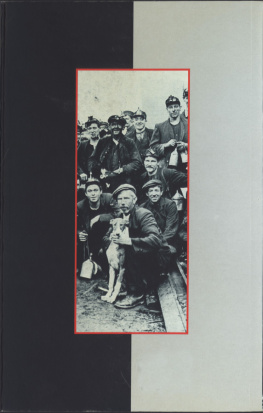

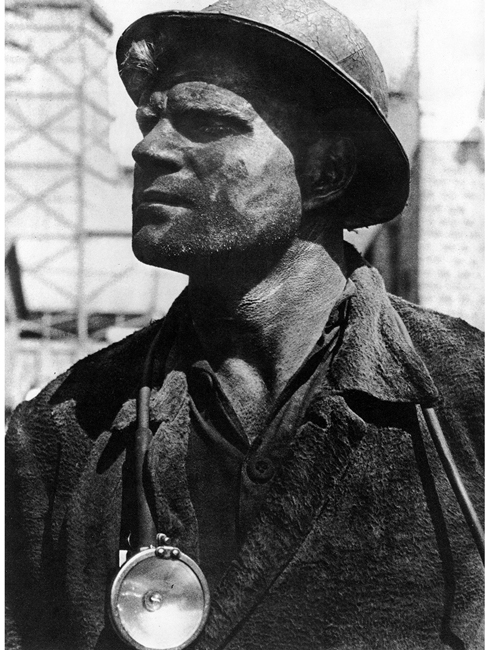

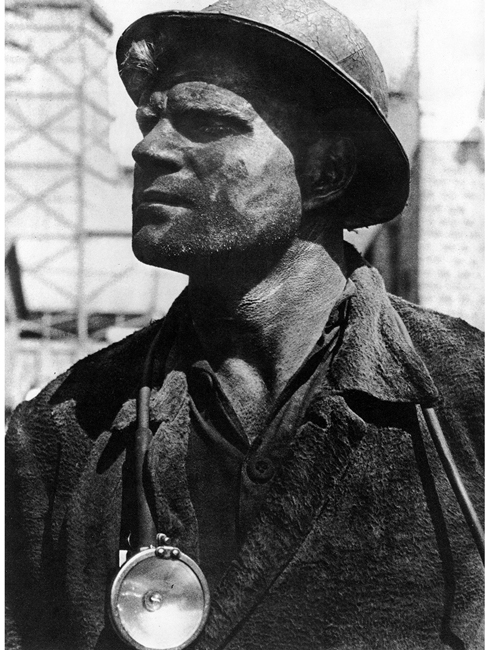

Markov-Grinbergs 1934 portrait of the heroic miner Nikita Alexeevich Izotov. The Francis Frith Collection.

In the sixteenth century the metallurgist Georgius Agricola described the nature and processes of mineral mining in a celebrated and very comprehensive treatise. Published as De Re Metallica, it became the standard work on mining for hundreds of years. Much of the power of the work derived from the way in which it was illustrated with wood engravings that helped to explain the technical processes (Agricola 1556). From the first moment of the scientific study of mining, then, visual imagery was central to the description and communication of its nature and processes (Agricola 1556). The photographer and critic Allan Sekula has argued that there is a clear line linking Agricolas famous work to subsequent prints, paintings and, later, photographic depictions of mining (Sekula 1983).

Agricolas study was a remarkable work, but coal mining was centuries old by the time he produced it. Indeed, it is often said that, after agriculture, mining was the earliest of human trades. The Chinese were digging coal out of shallow drifts more than 3,000 years before the birth of Christ. The Aztecs burnt it, and the Romans in Britain, as early as the second century AD, began a trade that carried coal from Newcastle to London. The seventeenth century saw the development of key technical innovations and a hundred years later deep coal mines were established in a number of countries. Long before this, though, coal was important to very early societies. Richard Martin asserts that one of the reasons for Chinas supremacy in the artistic and technological realms was because their use of coal provided plentiful and cheap energy. He adds that Many of the achievements of the later Han dynasty (206 BC to 220 AD) elaborate lacquerware, exquisite bronze work, the perfection of the papermaking process, and the development of the wind-powered bellows were made possible by this energy surplus (Martin 2015: 184).

But it is in the modern world that coal began to take centre stage, replacing timber as the primary source of energy. Indeed, it might be claimed that the mineral brought modernity about. In her influential book on coal, Barbara Freese puts it this way:

The industrial age emerged literally in a haze of coal smoke, and in that smoke we can read much of the history of the modern world. And because coals impact is far from over, we can also catch a disturbing glimpse of our future. (Freese 2003: 2)

The study of coal, then, is a way of exploring the past and predicting something of the future. For coal is a global commodity, and there is no part of the world that remains uninfluenced by it. Even if you could live in a country that neither mined nor burnt coal, global warming and the deleterious atmospheric consequences of burning coal would sooner or later affect you.

The centrality of coal to the making of industrial society means that it has been studied by people in many different disciplines, but our sense that we know something about mines, miners and mining communities comes largely from visual material, especially from photographs.

This is a book about coal, but also about photography. From its inception photography was concerned to reveal the hidden and dark places of the world. Great cities were trawled for images of the lives of the poor and the dispossessed. Indigenous peoples around the world were captured on camera, as were the noble ruins of vanished civilizations and the minutiae of natural history. But, for early photographers, coal mines were a particular challenge. They were socially and geographically remote from the centres of power, and it was difficult to photograph the work itself, for that took place under the earth in dark caverns that often contained dangerously flammable gases. Nevertheless, there are many early pictures of coal mines, miners, coal communities, and underground working. These were not the first images of mining, for from the eighteenth century there were numerous paintings, engravings and drawings of mine buildings, although they were often pictured from an aesthetic style that stressed their harmony with the surrounding rural scene, rather than the rupture that they made with it. Photography broke this sense that mining was an activity that might easily co-exist with agriculture and rural pursuits.

Coal is a very particular commodity, but it shares many features with other kinds of mineral mining. Gold, copper, nickel and zinc mining have all been extensively recorded, described and photographed. Some fascinating photographic studies have been made of these metals. The gold mines of South Africa are the subject of David Goldblatts book On the Mines. In her introductory essay to this book Nadine Gordimer observes:

The Witwatersrand created its own landscape out of waste and water brought from the underground in the process of deep-mining, and created its own style of living, inevitably following the social pattern of the colonial era of which it was a phenomenon, but driven by imperatives even deeper than the historical one. The social pattern was, literally and figuratively, on the surface; the human imperative, like the economic one, came from what went on below ground. (Goldblatt and Gordimer 1973: 19)

Next page