William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

HarperCollinsPublishers

1st Floor, Watermarque Building, Ringsend Road

Dublin 4, Ireland

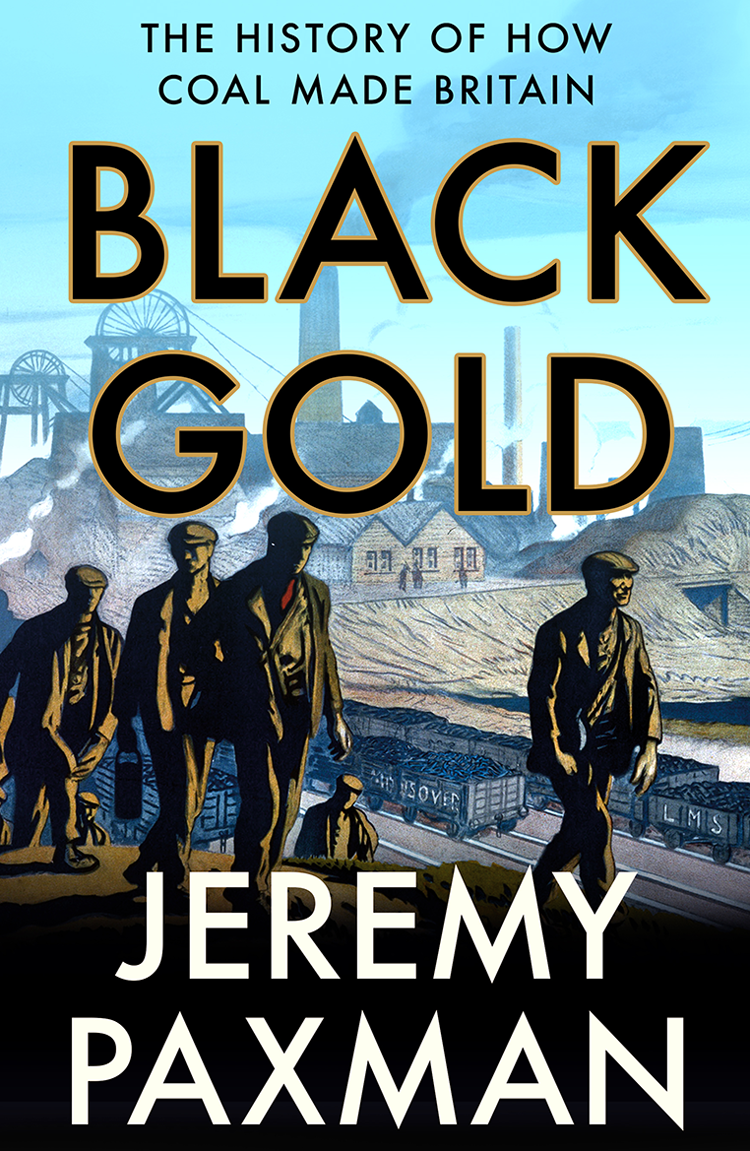

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2021

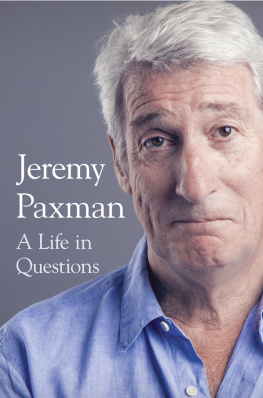

Copyright Jeremy Paxman 2021

Cover image Getty Images/Science & Society Picture Library/Contributor

Jeremy Paxman asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Wouldnt It Be Loverly (from My Fair Lady), Lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner, Music by Frederick Loewe 1956 (Renewed) Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe. All Rights Administered by Chappell & Co., Inc.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008128364

Ebook Edition September 2021 ISBN: 9780008128357

Version: 2022-08-24

For Jill, with gratitude for a stolen idea

The Hastings is a roadside pub in the village of Seaton Delaval, a few miles north-east of Newcastle. The pub (and village) are named after local landowners, who had been granted land by William the Conqueror and become abundantly rich, mainly on the proceeds of coal-mining. They had that instinct for survival which marks so many wealthy families with large estates. When they fell on hard times, they restored their fortunes through adroit marriage, after which they commissioned a fashionable architect to build them a massive stately home. Admiral George Delaval picked Sir John Vanbrugh, the architect of Blenheim Palace and Castle Howard, to build a magnificent English baroque pile in the early eighteenth century. These families intended to impress, and in that the Delavals were successful Vanbrughs designs were his last for a country house, and are thought by many to be his finest work. Seaton Delaval Hall is vast, with an enormous central courtyard of almost 2,500 square metres between two symmetrical wings. It is one of the grandest houses in Northumberland.

If they get that far, some of the 80,000 annual visitors to the Hall are entertained by the mausoleum in the grounds dedicated to a nineteen-year-old son and heir who died after being kicked in a vital organ while attempting to seduce a laundrymaid in 1775. If they but knew it, there is a much more dramatic story to be found in the village outside the gates of the majestic Hall. The families of the miners who worked in the new mine, which opened in the year of Queen Victorias accession, lived in 360 gimcrack cottages, supplied with water which had to be carried indoors from standpipes. There was, of course, no internal sanitation either. The village had three shops a tailor, a butcher and a grocer/draper. A few of the residents the local doctor, minister, stationmaster and some senior colliery officials had bigger houses, but the best of the miners homes contained two rooms downstairs, with a ladder leading to an attic. Most of the mine-workers lived five people to a house, and for those with large families, conditions must have been appallingly cramped. (The 1891 census shows Edward Ranshaw, a fifty-one-year-old miner, living in two rooms and an attic with a wife, six children, and two lodgers.)

Across the road from the Hastings pub is a branch of the local Co-op, successor to the shop founded by the residents in 1863 as the first miners co-op in Britain. It nestles behind a petrol station selling pork scratchings on the counter. In front of the pub, beneath a plastic sign offering Geordie Tappaz, and live sport on the bars numerous televisions, a middle-aged white man walks his two greyhounds on a leash. The pub doesnt look as if it is on a Campaign for Real Ale pilgrimage route.

But one Sunday in 1862 the place was besieged by huge numbers of customers. They had arrived by train, horse, carriage and on foot. The pub was, said a witness, literally swarming with visitors passages and staircases alike being impassable; and, with a callousness that is positively shocking, all are drinking, joking and enjoying themselves. The local police struggled to exert some sort of control outside the pub, by erecting temporary barriers. But it was the weekend, the Hastings was the only licensed premises in the area, and the sheer number of customers was simply unmanageable. Nothing draws a crowd like the chance to learn details of a tragedy. The visitors had come to try to discover what was happening literally beneath their feet.

Three days earlier, between ten and eleven on the morning of 16 January 1862, the second shift of the day had assembled for work at the colliery in the next-door village of New Hartley. The newly arrived miners were due to take over from what was called the foreshift, which had begun work in the middle of the night. Like most changeovers it was to take place underground, to save time and money for the mine operators, who did not want to pay men for the time they spent being dropped in cages down the mineshaft and then walking or crawling along underground passages to the face they were expected to chip away at. The pit had been sunk over fifteen years beforehand and had been an unlucky place from the start. Its predecessor had been closed in the 1840s, because it kept flooding. But, the mine produced good steam coal and its newly rich owner, Charles Carr all sideburns and waistcoat and with what was said to be the tallest top hat in the county believed that with a big enough steam pump to drain water from the pit, the coal could be extracted and sold. The machine made for him was one of the most powerful in the entire north-east coalfield, and built by one of the heavy engineering firms which had developed on the banks of the Tyne in the wake of the coal trade. The main cylinder of the beam engine was over seven feet across, pushing up and down an enormous horizontal girder over thirty-four feet long, made of cast-iron and weighing forty-two tons.

Shortly before eleven that morning, with a tremendous shattering noise, it broke in two. Part of the beam perhaps weighing over twenty tons fell down the shaft, which was the only way into and out of the mine. The accident had occurred at the worst possible time, when the maximum number of men were underground for the shift change. It would have been easier to manage a rescue had there been as existed at other pits two mineshafts. But the owners had followed local practice and sunk only one shaft into the earth, about twelve feet across. The shaft was divided in two all the way down by a timber partition or brattice to allow the usual mining ventilation system, in which clean air could reach the men underground through a down draught while a fire was kept burning low down on the up-cast side, to draw in the foul air of the mine and release it to the surface. If the single shaft became blocked for any reason as now happened tragedy would surely follow.

That morning a cage was being raised to the surface. Inside were eight men who had just finished their shift, doubtless pleased to be the first to have completed their time underground. When they were about halfway to the surface they heard a terrifying crack, followed by a roar, as the broken beam careered down the hole. Debris dislodged from the walls of the shaft, and bits of lift machinery struck the cage, snapping two of its four supporting cables. Four of the men inside the ungated cage were thrown out and plunged into the darkness below, as rock, metal and timber rained down upon them. The remaining miners knew their friends would not survive the fall. The massive beam continued its descent down the shaft, dislodging rock, rubble and heavy timbers as it fell. The rocks, rubble and rubbish then jammed across the shaft, blocking access to two of the three seams of coal; 204 men and boys were now trapped underground.