William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2016

Copyright Jeremy Paxman 2016

Lyrics from Mrs Worthington by Nol Coward, NC Aventales AG, 1935, reproduced by permission of Alan Brodie Representation Ltd, www.alanbrodie.com

Jeremy Paxman asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

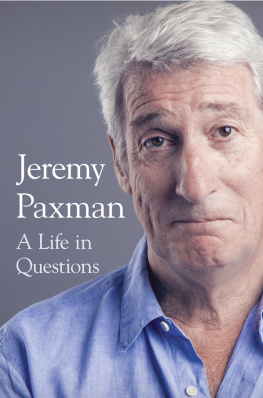

Cover image Carsten Windhorst

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008128302

Ebook Edition October 2016 ISBN: 9780008128319

Version: 2016-09-12

Here richly, with ridiculous display,

The Politicians corpse was laid away.

While all of his acquaintance sneered and slanged

I wept. For I had longed to see him hanged.

Hilaire Belloc

Contents

What do we know of our lives? I am certain my blood group is A Negative, because the nurse vaccinating me before some trip to a war zone sent a blood sample off for testing. I noticed that, in private, we all scrawled our blood group onto the back of our helmets, in case something awful happened. I know I passed my Eleven-Plus, took two attempts to get good enough marks at my Common Entrance exam, failed Maths and Latin O Levels at the first attempt, got pretty average A Levels, won an exhibition to Cambridge and got a 2:1 in my final exams. The mere facts which categorise you arent interesting. If only one could tell children that once youve finished your exams, no one cares much about how you did, or even asks to see your certificates. Instead we expect them to play the game we played.

When the time came for me to start work I applied for the obvious jobs, but without much enthusiasm. I was then astonishingly lucky. One of the irritating characteristics of life is that it can only be understood looking backwards, yet you must live it looking forwards. Though it didnt really seem like that at the time, I now see that there was only one occupation suitable for someone who, like me, was driven by curiosity and loved words. For over forty years I have followed the same trade, whether in radio, television, newspapers or books.

As my own shelves show, the world has a surplus of books. Why perpetrate another? I have no great prescription to dispense. But its been fun, and along the way I met some interesting people and heard some terrific stories, which I might as well share before I forget them. I have no scores to settle, no unfinished business. I just did things that seemed interesting at the time. A collection of memoirs offers the chance to try to set the record straighter than it might be otherwise, and to laugh at the silliness of so much of life.

The other day I was rootling through some boxes in the bottom of a cupboard. Whatever the reasons for keeping the stuff I found inside the hours devoted to an essay, the brief moment of insight which seemed so vital at the time, the transitoriness of television earlier in life I wanted to preserve my past. I have now lost that urge. There, among the Panamanian hotel bills, Swiss speeding tickets, defunct fishing permits, libel-reader reports and now unplayable videocassettes, was the evidence that I was once vain enough to subscribe to a cuttings agency, which dutifully clipped pieces from newspapers and magazines across the land. I suppose I kept the subscription for a year or two, and it is embarrassing to confess. For a while, my head was turned. Even after deciding that the agency was a waste of money, I still occasionally clipped stories from the newspapers in which I had appeared. From them I learn, among other things, that my weather forecasting colleague on Breakfast Time was a sex machine, and that a Scottish sports reporter on the same show with a squashed face was tipped as the future of broadcasting. I seem once to have told a celebrity magazine called Best that I find clothes really boring, and soon afterwards a designer called Jeff Banks nominated me as one of the worst-dressed men in Britain, saying, That man should loosen up and get into some soft linen. In 1994 Ruby Wax told Options magazine that she had noticed I had huge genitals, and in March 2008 Marks & Spencer took a full-page ad in the Guardian to proclaim that I was wrong about the drop in quality of their pants. David Cameron let it be known to some obliging reporter that he detested me. Tony Blairs Health Secretary, John Reid, accused me of disrespecting him after I described him on air as the governments all-purpose attack dog (the ten minutes of foul-mouthed abuse which his assistant afterwards heaped on Kate McAndrew, the producer of the day, was not disclosed), and the next day the Daily Mirror quoted a friend of John Reid calling me a West London wanker. In the following weekends papers the novelist Howard Jacobson accused me of coarsening public life.

The accusation is familiar, along with the suggestion that people like me are responsible for the fact that so many of the public despise mainstream politicians. I reject the charge, of course all we try to do is to get straight answers to pretty straightforward questions, and often a cloud of obfuscation is as revealing as an unexpected outbreak of frankness. But I accept that if you present yourself uninvited in peoples homes, they will take a view on you. Thats how it goes. In my case the progression of newspaper-columnist opinion went from a breath of fresh air, through Who does this cheeky bastard think he is?, to peevish old sod. It is intrinsic to the trade I follow that we constantly seek novelty, and once the novel becomes familiar, it is ripe for aerial bombardment. The only hope then is that in the years when youre wondering where you left your teeth before your afternoon nap, someone reaches for another clich and deems you to have become a veteran as if you are a car on the LondonBrighton run, and unlikely to get much beyond Croydon. Then you die.

There were dozens of letters in the cupboard, too a tiny fraction, I suppose, of the total I received, and which I had kept for no rhyme or reason I could discern. I rather enjoyed hearing from viewers, since broadcasting is such a one-way business, and letters often described a first-hand experience of issues which would otherwise be hidden behind clouds of political verbiage. Since anyone who presents news or current affairs programmes on the BBC is effectively an employee of the viewers who are forced to pay the licence fee, they are perfectly entitled to say what they think of them. (Anyone who performs the same role on a commercial channel is also paid for by the viewer, of course, but rather more indirectly.) I relished the exchanges which often followed, and only a handful of times had to use the tabloid editor Kelvin MacKenzies tactic, which was to tell my correspondent that I would reluctantly have to ban them from watching. This generally led to even angrier letters, protesting, You cant do that I pay the licence fee!

I discovered that generally, if youve made a mistake it is best to answer a letter of complaint with Youre quite right. Im so sorry. Ill try to do better. This often has the complainant writing back to say, Oh, please dont take it too seriously. The nuclear option is to employ the tactic refined by the former Prime Minister of New Zealand, Rob Piggy Muldoon: Dear Mrs Smith, I think you should know that some lunatic is using your name and address to send offensive letters in the post. I perhaps sent something similar to the man who wrote from Sutton in Surrey during a journalists strike I supported in 1985. He described how he had arrived home, blessing my luck at not having to look at you on television. Then I picked up the