JEREMY PAXMAN

Empire

What Ruling the World Did to the British

VIKING

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3

(a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

(a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published 2011

Copyright Jeremy Paxman, 2011

BBC logo copyright BBC, 1996

The moral right of the author has been asserted

By arrangement with the BBC: the BBC and the BBC logo are trademarks of the British Broadcasting Corporation and are used under licence

Jacket design: Superfantastic

Jacket images Kimball Stock

All rights reserved

Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book

The chapter epigraph on is taken from The Siege of Krishnapur by J. G. Farrell, published by W&N Fiction, a division of the Orion Publishing Group, London. Reproduced with permission

ISBN: 978-0-67-091960-4

By the same author

Friends in High Places

Fish, Fishing and the Meaning of Life (editor)

The English

The Political Animal

On Royalty

The Victorians

For Elizabeth, Jessie, Jack and Vita, for whom the imperial project meant long periods of either mental or physical separation. Independence is at hand

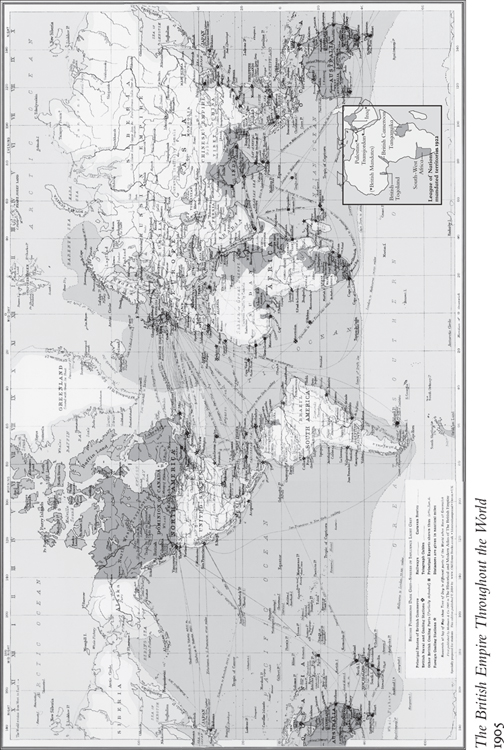

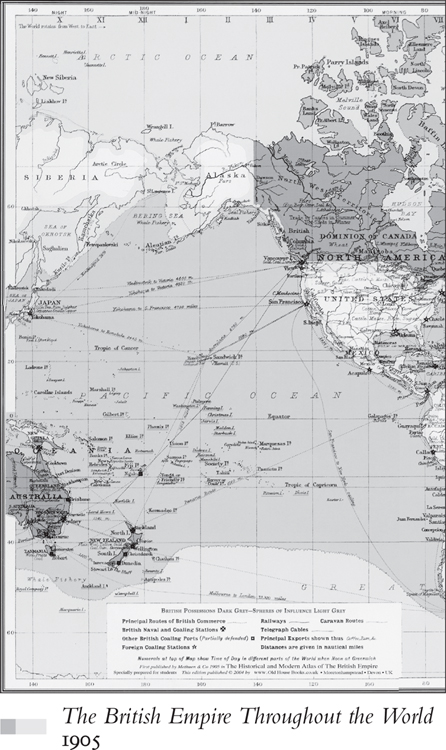

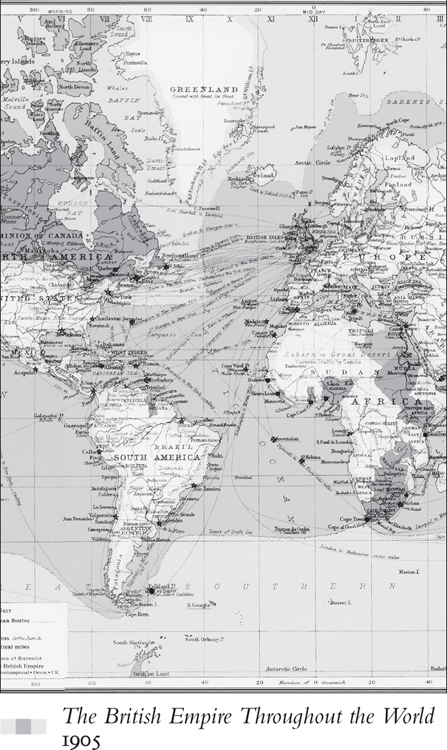

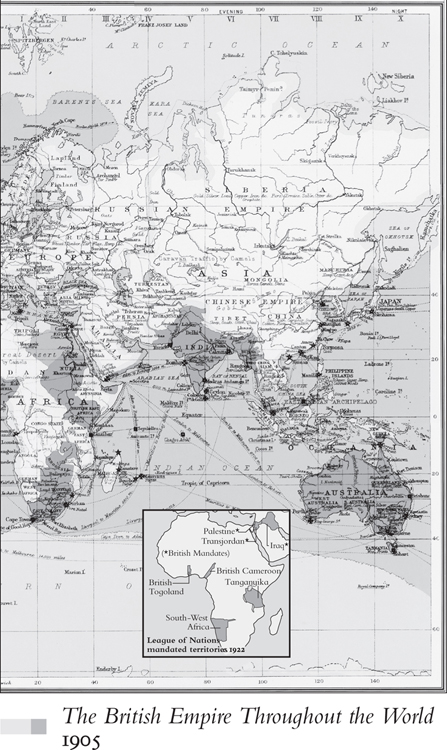

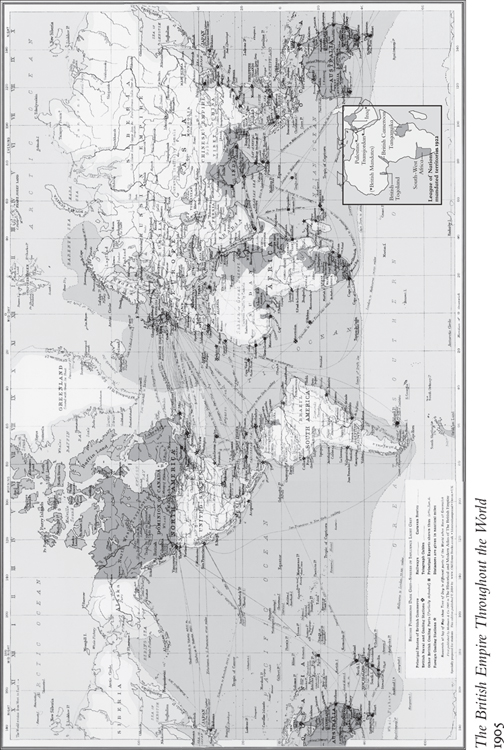

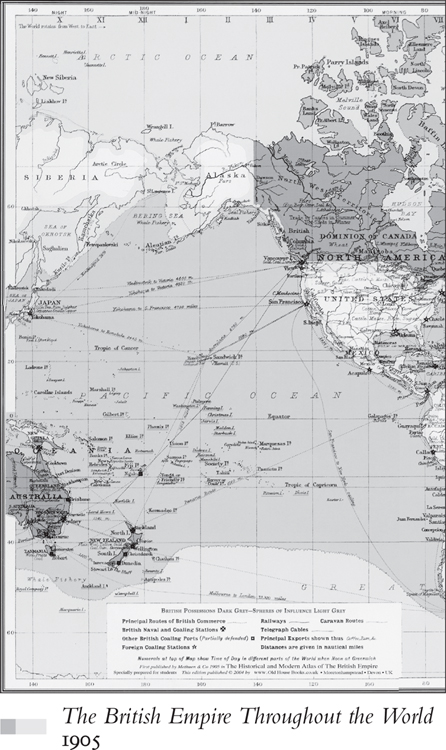

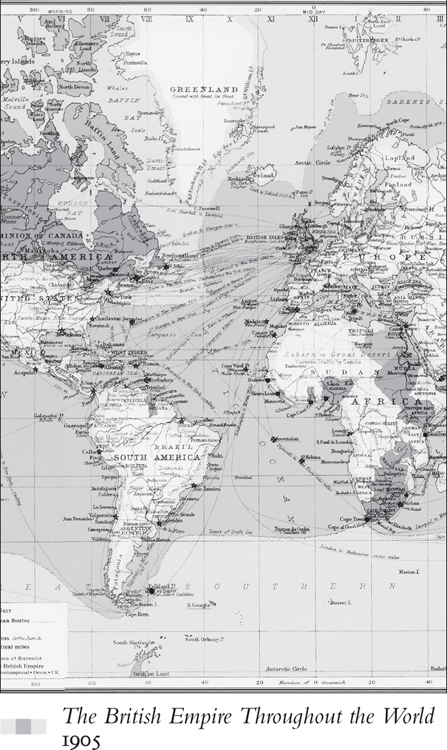

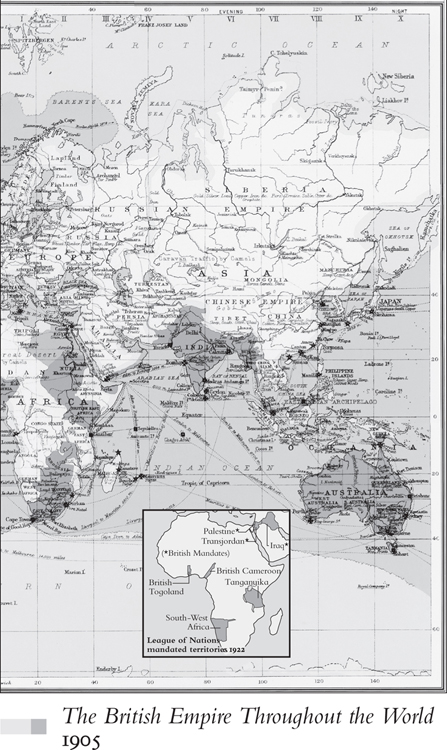

MAP

The British Empire Throughout the World 1905

Introduction

It seems such a shame when the English claim the Earth That they give rise to such hilarity and mirth

Nol Coward, Mad Dogs and Englishmen, 1931

Youre a Brit, arent you? It was an accusation. His face was twisted, angry and only about six inches away from mine. His breath was beery. I was backed against a wall outside a drinking club in west Belfast, and two of his friends stood on either side there was no chance of running for it. This is how it begins, I thought, starting to panic. It ends with a beating in a lock-up garage or the back of a pub somewhere. Or worse.

It didnt, of course. Within less than a minute an older man had said something and the three youths laid off, sauntering away without a word: next time it really might be an undercover British soldier. I knew what a Brit was, all right. But I had never been called one until I arrived in Northern Ireland to cover the war there in the 1970s. Belfast was a dark place and not just because its street lights had been knocked out in the many battle-zones across the city. It was a conflict murky with injustice, bigotry, exploitation, long memories and short fuses. The terminology reflected what you thought the violence was. The British preferred to call the everyday bombings, gunfights, murders, military funerals and armoured cars on the streets the Troubles. It might look like a war, but it wasnt. To the IRA, the violence was definitely part of a war to force the British out of the last corner of their Irish colony. The loyalist settler community, almost exclusively the descendants of Scots and others who had been brought to Ireland to make the place safe for England, fought for the right to remain British, despite not living in Britain. The epithet Brits referred to the apparatus of imperialism, specifically the army, and by extension all of us who came to Ireland from England, Wales or Scotland, although it was really the English who were hated. I did not much like the term.

I had arrived in Ireland woefully ill-equipped to understand what was happening there. Anti-colonial wars belonged to another time in history. This is even more the case for many British people now: the average age in Britain is forty, which means that apart from a vague awareness of the war to reconquer the Falkland Islands or the ceremonial handing back of Hong Kong to the Chinese in 1997, most citizens have little sense of Britain as an imperial power.

Anyone who has grown up or grown old in Britain since the Second World War has done so in an atmosphere of irresistible decline, to the point where now Britains imperial history is no more than the faint smell of mothballs in a long-unopened wardrobe. Its evidence is all around us, but who cares? It is the empty fourth plinth at the north-west corner of Trafalgar Square that interests us, not the three that are occupied by a king and a couple of imperial generals. Ask us what those generals did and were lost. Even the most exotic empire-builders have sunk from our minds. Charles Gordon is a good example. His unhinged mission to Khartoum and subsequent beheading raised him to saint-like status in Victorian Britain. A statue, showing the great martyr befezzed and cross-legged on a camel was placed in the middle of the traffic at the main crossroads in Khartoum, to remind the Sudanese who was boss. At independence in 1956 they took it down and sent it back to England, where it was re-erected at the school in Woking founded at Queen Victorias behest as a memorial to the general. It stands there, grey and unexpected, to this day. They used to tell the story of a small boy taken after church each Sunday to admire the national hero. After several weeks veneration, the child asked, Daddy, who is the man on Gordons back? But even the jokes have passed into history now.

And yet the sense of being British is clearly very different to being, say, Swedish or Mexican. No one would have a Mexican up against a wall in Ireland because of his nationality. Ever since the moment when I realized that there were people who saw me differently because of my countrys history, I have wondered what that history has done to us as a nation. We think we know what the British Empire did to the world. But what did it do to us?

Next page