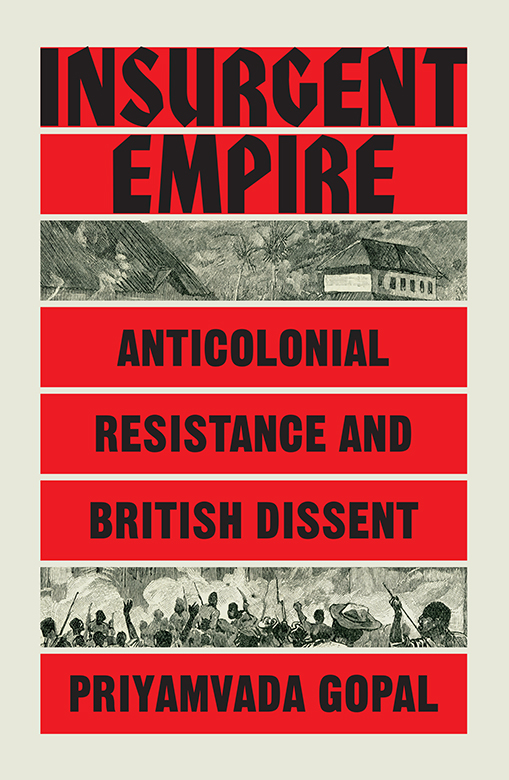

Insurgent Empire

Insurgent Empire

Anticolonial Resistance

and British Dissent

Priyamvada Gopal

First published by Verso 2019

Priyamvada Gopal 2019

Every effort has been made to ascertain the copyright status of images appearing herein and, where necessary, to secure permission. In the event of being notified of any omission, Verso will seek to rectify the mistake in the next edition.

The images reproduced here are in the public domain, with the following exceptions: Shapurji Saklatvala speaking to crowds at Speakers Corner, Hyde Park, September 1933 Keystone / Getty Images; The League against Imperialism canvassing at, Trafalgar Square in London in August 1931 Fox Photos / Getty Images; Nancy Cunard in her print studio in France Keystone-France / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images; C. L. R. James giving a speech at a rally for Ethiopia in London Keystone-France / Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images.

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-412-6

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-415-7 (US EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-414-0 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gopal, Priyamvada, 1968 author.

Title: Insurgent empire : anticolonial resistance and British dissent / Priyamvada Gopal.

Description: London ; New York : Verso, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019005764 | ISBN 9781784784126 (hardback : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781784784157 (US ebk.) | ISBN 9781784784140 (UK ebk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Anti-imperialist movements Great Britain History. | Great Britain Colonies History.

Classification: LCC JV1011 .G66 2019 | DDC 325/.341 dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019005764

Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

Contents

I n the early summer of 2006, I took part in an episode of Start the Week, the BBC radio show hosted by prominent journalist Andrew Marr. The topic was the British Empire and my fellow guests were the theologian Robert Beckford, the historians Linda Colley and Eric Hobsbawm, and, most significantly in this context, the media face of the case for British imperialism Niall Ferguson. Although I was familiar with the unquestioned celebration of imperial figures such as Winston Churchill and the silence around the more questionable legacies of the empire which Churchill famously didnt wish to liquidate, this programme was my first close encounter, after moving to Britain in 2001, with bullish assertions about the greatness of Britains imperial project and the benevolence of its legacies. In this mythology, a version of which is peddled in Fergusons book on the British Empire and accompanying television series, massacres, violence, slavery and famine were acknowledged as passing unfortunate occurrences rather than as constitutive dimensions of imperialism. While both Colley and Hobsbawm demurred from the matey complacency which marked Marrs and Fergusons dialogue on the topic, it was largely left to Beckford and me, the two people of colour on the panel, to raise doubts about the benevolence and munificence which was being attributed to the British Empire. We made rather more of the land grabs, dispossession, racism, enslavement, expropriation, ethnic cleansing and resource theft that had taken place over centuries and continued to have lethal afterlives in those countries which had felt the heavy hand of colonial rule on their backs. That in itself was perhaps unremarkable but more striking was the palpable shock and outrage that Ferguson felt at being denied a free pass on a string of questionable assertions. A vituperative opinion piece from him would follow, and he would reference the episode almost obsessively elsewhere.

That evening the BBC took the unprecedented step of replacing the usual repeat of the mornings episode with a phone-in programme to discuss the mornings barny, the term Marr used to refer to the exchange. Sitting alongside him in what can only be described as an embarrassingly proto-colonial gesture was a young American woman of Indian descent whose main purpose, it would seem, was to reassure the BBCs listeners that I by no means represented young Indians who, she suggested, were either indifferent to or very positively disposed to the Empire. In a particularly bizarre piece of apparently clinching evidence, she noted that her grandfather, who had grown up in British India, routinely saluted her white husband when they visited him. This incident and the significant amounts of both angry and appreciative mail I received after writing a related piece for the Guardian newspaper heralded what would become for me a somewhat unexpected dozen years of engagement with Britains relationship to its imperial past and the manifold silences and lacunae in the British public understanding of that past. My own students at Cambridge, studying what was then coyly referred to as Commonwealth Literature, came to class with very little knowledge of what the Empire was or how it lived on in the present and were, to their credit, keen to know more. It became clear to me that some form of reparative history was desperately needed in the British public sphere which is still subject to a familiar ritual where politicians of various stripes will periodically announce that Britain has nothing to apologize for or call for active pride in the legacies of the Empire. These calls often sit alongside the somewhat contradictory claim that to criticize imperial misdeeds, supposedly by the values of our time, is an anachronistic gesture.

But is it anachronistic to subject the Empire to searching criticism? This book is in part a response to that question and in part a very different take on the history of the British Empire to what is generally available in the British public sphere. In academia, a retrograde strain of making the so-called case for colonialism is now resurgent. As a scholar whose prior work had been on dissident writing in the Indian subcontinent as it transitioned to independence, I was aware that all societies and cultures have radical and liberationist currents woven into their social fabric as well as people who spoke up against what was being done in their name: why would Britain in the centuries of imperial rule be an exception? At the same time, I also wanted to probe the tenacious mythology that ideas of freedom are uniquely British in conception and that independence itself was a British gift to the colonies along with the railways and the English language. The result is a study which looks at the relationship between British critics of empire and the great movements of resistance to British rule which emerged across colonial contexts. The case against colonialism, it will be seen, was made repeatedly over the last couple of centuries and it emerged through an understanding of resistance to empire.

My first thanks are to those historians whose vital scholarly texts on British critics of empire I have drawn on extensively: Stephen Howe, Gregory Claeys, Nicholas Owen, Mira Matikkala and Bernard Porter. Writing this book through their work in an age where higher education and research are being privatized and monetized, I have been repeatedly reminded of how fundamentally collaborative the production of knowledge is. I have also learned a great deal from the work of pioneering scholars of anticolonialism, such as Hakim Adi, Marika Sherwood, Mimi Sheller, Brent Hayes Edwards, Anthony Bogues, Ken Post, Gelien Matthews and Minkah Makalani. My mistakes, of course, are not theirs. I am grateful to the Leverhulme Trust for taking a chance on this project and granting to me a two-year research fellowship that enabled substantial amounts of work towards this book. The Faculty of English at the University of Cambridge and Churchill College have also generously provided additional research monies. It would be unseemly not to acknowledge both the BBC and Niall Ferguson for setting me off on a road to discovering a trajectory of British thought and political practice so different from the mythologies they routinely and damagingly peddle. I hope Ferguson will forgive the temerity of an obscure Cambridge lecturer, as he has dubbed me, in daring to venture into terrain where only the mighty may expound.

Next page