This book took a very long time to finish. Its first iteration was as my dissertation at Rutgers University. The history faculty I worked with there showed me what good colleagues, good teachers and good scholars look like. My advisor, John Gillis, has always been exactly what I needed critical, enthusiastic and patient, in equal measure. I was lucky that he saw something in my original proposal and then let me take the time to discover something much better. Hes been a very good friend and an excellent role model as both a professor and a mentor. Similarly, Im grateful to my dissertation committee Matt Matsuda, Joan Scott and Al Howard who all gave not only guidance and criticism but also the space to follow my own path. Dorothy Helly, my mentor since undergraduate years at Hunter College, continues to demand my best effort and I thank her for it.

The conversations and debates with fellow students shaped me as a historian, as have the friendships with other members of the Rutgers alumni Ive been lucky enough to remain close to today. I would never have finished this book without the intellectual engagement Ive had, then and now, with Brady Brower, Lindsay Braun, Brian Crim, Gary Darden, Justin Hart, Sarah Gordon, Patrick McDevitt, Tammy Proctor, Jennifer Tammi and Chuck Upchurch. Their respect and support have been a great gift.

I worked on this project intermittently for many years. During that time, core members of the Midwest Conference on British Studies kept me inspired and excited through their work and offered me a community where I could continue to engage with fellow British Studies scholars even when I wasnt able to publish. There were many others whose contributions to MWCBS conferences informed my work, but Id like to thank in particular Jennifer McNabb, Jason Kelly, Eric Tenbus, Bob Bucholz, Christine Haskill, Warren Johnston, Carol Engelhardt and Jennifer Hart.

Alice Ritscherle and Susie Steinbach read portions of the manuscript. I want to thank them for their incredibly useful critique, as well as the feedback from anonymous readers and my editor, Tomasz Hoskins, at I.B. Tauris/Bloomsbury. I would also like to thank Anna Davin for her generosity and encouragement. Two other British historians are completely unaware of how much they are responsible for this book being published. James Vernon and Susan Kent were encouraging at a moment when I was ready to abandon it altogether. My colleagues at Slippery Rock University are a pleasure to work with and I thank them for their support. Im very lucky to be among peers who see traditional scholarship as part of a larger package of intellectual engagement.

My research took me to many archives and libraries where I had the good fortune to be helped by literally dozens of excellent archivists, librarians and technicians. I want to mention two of them. Jay Barksdale, the long-time librarian in charge of the Wertheim Study at the New York Public Library, always found room for me there during the narrow windows when I was able to work. And Jane Hogan, the head archivist of the Sudan Archive at Durham University, was (and still is) incredibly knowledgeable and a pleasure to work with. Her contribution cannot be overstated.

I want to thank Sylvie Bertrand, Brian Gallagher and Kara Stanley for decades of love and support. Finally, my parents, Barbara and Jerome, raised their daughter to be intellectually curious, up for adventure and stubborn. Their unflagging confidence in me was probably their greatest gift. I wish my father were still here so that he could read the final product. My husband, Edmund, who has lived with this project almost as long as I have, is a blessing to me every day. Thank you.

In 1989, Martin Daly and Francis Deng published a collection of interviews with British and Sudanese government officials during the period of British rule in Sudan from 1898 to 1956, when the country was officially the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium of the Sudan. Most of the British contributors to Bonds of Silk make the wonderfully contradictory assertions that knew nothing about the Sudan or its people before they began their careers there, but they remembered being enthusiastic about joining the administration because of what they had heard about the place. How can both statements be true? Britons who went to the Sudan made a particularly momentous decision when they chose colonial careers that would separate them from their families, friends and communities because they were not, for the most part, from multigeneration imperial families. It seems counterintuitive that they would choose to go to a country and rule over a people they knew nothing about; the second statement that they were motivated by their knowledge of the place seemingly makes more sense. They did their homework; they familiarized themselves with the history of the country, its people, religions and geography and then decided on careers that would take them there. But this simply wasnt the case. The British interview subjects dont hesitate to admit their ignorance before they landed. And yet the country and its people brought them there.

This book aims to reconcile those two statements. These men, and later their wives and other women who joined the Sudan government, thought they knew the Sudan before they got there. They also thought they knew what being colonial administrators was all about. This knowledge motivated them to pick the Sudan as the location and colonial administration as a career. Only once they got there did they realize just how deeply ignorant they were about the country and its people and about the work they had chosen. They spent the rest of their careers slowly moving away from this starting point of absolute confidence and total ignorance. But as they charted their own journey they increasingly diverged from the metropolitan knowledge of the Sudan and colonial administration. They struggled to be who their friends, families and government thought they were, while coming to grips with just how little in their view the British public and its decision-making bodies understood imperial territories in general, the Sudan in particular and the many peoples under their control.

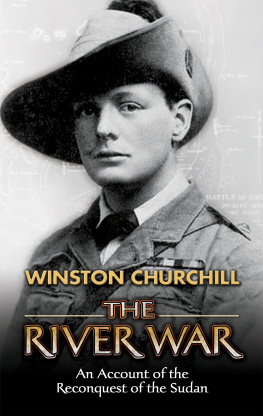

One reason for the administrators paradoxical responses to Deng and Dalys interview question was that the Sudan figured large in the imperial adventure stories, poems, songs and movies they had encountered as children and adolescents. And the Sudans entrance into the British publics consciousness coincided with the beginning of mass marketing of the Empire the advent of High Imperialism in the 1880s and 1890s. A shared vocabulary of the Sudan stretched across multiple media platforms with a vividness and coherence that earlier and later colonial narratives lacked. The tragedy of General Charles Gordon and the siege of Khartoum in 1884, and General Herbert Kitcheners triumph and the reconquest of the Sudan in 1898, were events collectively experienced by the British public produced and responded to in new media and a new context of representational mass politics.

From the moment probationary officers were accepted into the Sudan government, they were confronted by different texts about the Sudan and about colonial careers than those their metropolitan peers had consumed. In the early days of the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, many of these journals, memoirs and treatises reinforced established images of Gordon and Kitchener rather than debunked them. After the Great War, however, the demand from the British government and officials in the Sudan government for improved and modernized training resulted in a substantial, standardized period of inculcation prior to their departure. These interwar recruits were exposed to a curriculum that undermined the knowledge that mass-produced literature about the Sudan had led them to believe they possessed.