COLONIALISMS

Jennifer Robertson, General Editor

i. Doctors within Borders: Profession, Ethnicity, and Modernity in Colonial Taiwan, by Ming-cheng Lo

2. A Different Shade of Colonialism: Egypt, Great Britain, and the Mastery of the Sudan, by Eve M. Troutt Powell

3. Living with Colonialism: Nationalism and Culture in the AngloEgyptian Sudan, by Heather J. Sharkey

4. Colonizing Sex: Sexology and Social Control in Modern Japan, by Sabine Friihstiick

HEATHER J. SHARKEY

The generous support of many institutions made this project possible. In 1990, four years before this research even started, the British Government and Marshall Aid Commemoration Commission granted me the Marshall scholarship that sent me to the University of Durham, where my love for Sudanese history first began to grow. During the 1995-96 academic year, the U.S. Department of Education awarded me a Fulbright-Hays fellowship for research in Egypt, Great Britain, and Norway. Grants from the AmericanScandinavian Foundation (Crown Princess Martha Friendship Fund), and from four Princeton University sources-the Council on Regional Studies, the Program in Near Eastern Studies, the Center of International Studies (Boesky and Sternberg Funds), and the Department of History-supported research trips to Norway (1994) and the Sudan (1995). Fellowships from the Mrs. Giles Whiting Foundation, the Josephine De Karman Trust, the Woodrow Wilson Foundation (Princeton Society of Fellows), and the A. W. Mellon Foundation enabled me to devote the 1996-97 year to writing and completing my dissertation. In 1999 a grant from the Kelly-Douglas Fund at MIT enabled me to undertake a follow-up visit to British archives.

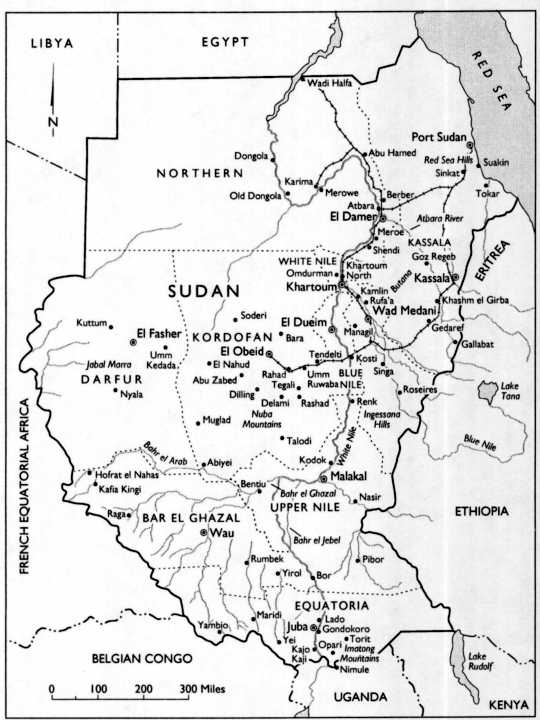

Many individuals read the manuscript at different stages of its development and offered invaluable advice. I owe thanks to Robert L. Tignor, L. Carl Brown, R. S. O'Fahey, M. W. Daly, Abdullahi Ibrahim, Lora Wildenthal, Endre Stiansen, John O. Voll, Lynne Withey, and the readers of the University of California Press. Several colleagues offered insights and suggestions in the course of research, including Peter Woodward, Yoshiko Kurita, Albrecht Hofheinz, Anders Bjorkelo, Robert O. Collins, Fadwa Abd alRahman Ali Taha, Robert Kramer, Anita Fabos, and Ahmed Shouk. Many individuals also took the time to share their knowledge in letters, conversations, and interviews. In this regard, I am grateful to Abd al-Rahman Abu Zayd, Ismail al-Atabani, Sir Michael Atiyah, Patrick Salim Atiyah, Ahmad Safi al-Din Awad, Muhammad Hashim Awad, Jala' Ismail al-Azhari, Qasim Badri, Michael Cook, Sir Donald Hawley, Charles Issawi, Muna Shami Jurdak, Sirr al-Khatm al-Khalifa, A. H. M. Kirk-Greene, Phillippa Maghrabi (Mrs. Abd al-Fattah al-Maghrabi), Sadiq al-Mahdi, Rene Malouf, J. A. Mangan, Yunan Labib Rizq, Maryam Mustafa Salama (Mrs. Ismail al- Azhari), the late G. N. Sanderson, Amin al-Tum Satti, Abd Allah al-Tayyib, Graham Thomas, and J. O. Udal. Still others facilitated my use of archives and research centers, notably Jane Hogan, Beth Rainey, and Lesley Forbes of the Durham University libraries; Ali Salih Karrar and Muhammad Ibrahim Abu Salim of the National Records Office in Khartoum; Knut Viker of the Centre for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies at the University of Bergen; Haydar Ibrahim Ali of the Sudanese Studies Center in Cairo; and staff members of the C.M.S. archives at Birmingham University, the Wellcome Institute in London, and the manuscripts and special collections divisions of Edinburgh University and the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). Librarians at Princeton, MIT, and Trinity College worked wonders in securing Arabic and English books through interlibrary loan. Kate Warne and the staff at the University of California Press guided the manuscript smoothly to completion. I also thank Rosalind Caldecott, who designed the map of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan that is available to researchers at the Sudan Archive in Durham.

In the Sudan, Batoul Mukhtar Muhammad Taha and Imad Ali Idris showed boundless hospitality in their home in Hillat Hamad, Khartoum North. Through their example, I came to understand why the Sudanese are famous for their dignity and grace. Many others also showed their kindness in Khartoum, including John and Koki Bodourian, Anis Haggar, Fudi Malouf, George and Eleanor Pagoulatos, and the staff of the National Records Office. In Cairo, members of the extended Eveready-Energizer corporate "family" made my stay more comfortable and showed a genuine concern for my well-being. In Durham, the staff of Palace Green Library extended a warm welcome, as did the Hogan family and Alec CummingBruce. In Bergen, I found my place among the affiliated members of the "Senter for Midtausten- og islamske studiar," who introduced me to the beauty and pleasures of Norway while offering keen intellectual companionship. At Princeton, and later at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, MIT, and most recently, Trinity College, I enjoyed the friendship and encouragement of many colleagues.

While my debts of gratitude are many, I thank my family above all, for their unstinting love and support over the course of so many years. I there fore dedicate this book to my mother and father, Jane and Richard Sharkey; to my five sisters and brother-Donna, Diana, Jill, Joanne, Brian, and Jennifer; to my parents-in-law, T. R. and Jaya Balasubramanian; and to my husband, Vijay Balasubramanian. As my best friend and sidekick, Vijay shared in my adventures throughout the book's creative process, and lived with Living With Colonialism almost as much as I did. When this book was nearing completion, our baby boy, Ravi Nicholas Balasubramanian, came into this world and blessed us with great happiness.

To my family

In transliterating from Arabic, this book follows the system used in the International Journal of Middle East Studies. Diacritical marks are omitted, except for the ayn () and hamza () when they occur in the middle or at the end of words. Exceptions are the terms marnur and ulama, which appear in The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, 1993 edition. Note, too, that since the term mamur was used widely in British English sources, it is not italicized as a foreign word. Unless otherwise indicated, translations from Arabic into English are the author's own. Moreover, Sudanese place names are spelled according to British usage of the period, as set out in Permanent Committee on Geographical Names for British Official Use, First List of Names in the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan, 1927. Finally, in identifying individuals, I have indicated birth and death dates, when they are known.