ISLAM, NATIONALISM AND COMMUNISM IN A TRADITIONAL SOCIETY

By the same author

The Sudan Under Wingate

ISLAM, NATIONALISM AND COMMUNISM IN A TRADITIONAL SOCIETY

The Case of Sudan

GABRIEL WARBURG

First published 1978 by

FRANK CASS AND COMPANY LIMITED

Published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1978 Gabriel Warburg

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Warburg, Gabriel

Islam, nationalism and communism in a traditional society

1. Sudanese Communist Party History

2. Islam and politics Sudan

3. Communism and Islam

329.9624 JQ3981.S873S/

ISBN 13: 978-0-714-63080-9 (hbk)

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher in writing.

Typeset by Computacomp (UK) Limited, Fort William, Scotland

Contents

The studies contained in this volume have one thing in common: they describe the overwhelming impact of Islam on Sudanese society and politics from the formative years of the Sudanese political community until the abortive communist coup in July 1971.

The first study describes the creation of the Umma party and deals with the most important force within the religio-political structure of the Sudan.* It gives an account of the emergence of sectarian politics, in the Anglo-Egyptian setting, and analyses its roots and the reasons for its success.

The second chapter of men of the Khatmiyya and the Anr, were always behind the scenes when it came to crucial decisions.

of this volume is a study of Sudanese Communism in which I became interested for two main reasons. First, I wanted to find out whether it was possible for a political force which is diametrically opposed to religion to thrive in a traditional and Islamic-dominated society without compromising itself. Secondly, knowing the relatively important role which the Sudanese Communist Party (SCP) played in the 1964 civil revolt which overthrew Abbds military rgime, as well as its direct involvement in the abortive anti-Numeir coup in July 1971, I was tempted to investigate the real force which is represented by Sudanese Communism.

During the last few years three books have been published dealing with communism in the Sudan, which contain documents of the SCP in their original Arabic.* I was also fortunate in obtaining a number of documents and publications of the SCP from the British Communist Party. All of these sources proved extremely useful for the preparation of this study. However, the gaps which remain in our knowledge of the SCP are still considerable and are likely to remain so in the foreseeable future.

The study on Communism is divided into three main sections. The first (), I have chosen four topics which I regarded as crucial in attempting to understand the ideological framework of the SCPs policies. The first examines the SCPs attitude towards Egypt as well as its views on Arab unity and on the ArabIsraeli conflict. The other three deal with internal Sudanese policies: sectarianism and the SCPs attitude towards Islam; the problem of the South; and the SCPs attitude towards military coups leading to the partys split in 1970.

In section three (Fud Malars book mentioned above. The other three are reprinted from the English version, which I obtained from the International Department of the Communist Party of Great Britain.

The reason why the Soviet Union hardly features in my present study is that its relations with Sudan were unaffected by the ups and downs of the SCP. As in other countries in Africa and Asia the communist bloc was unhampered in its dealings with the Sudan by the ideology or policies of the rgime. Thus, during the military government of General Abbd, SovietSudanese relations flourished, though the SCP was outlawed and all its known leaders imprisoned. It therefore seemed meaningless to deal with SovietSudanese relations in a study devoted to the internal intricacies of communism in the Sudan.

Finally, I would like to thank Professors Zbigniew Brzezinski and J. C. Hurewitz, both from Columbia University, who advised me during the early stages of my work; as well as Professor Oles Smolansky from Lehigh University and Dr. Wolfgang Berner of the Bundesinstitut fr Ostwissenschaftliche Studien, in Kln, for their many useful suggestions made upon reading the first version of my study on Communism.

1978

G.W.

, dealing with Sudanese Communism, was researched and written under the auspices of the Research Institute on Communist Affairs and the Middle East Institute, both at Columbia University, which kindly offered me a research fellowship. It is published in this volume for the first time.

* usayn Abd al-Rziq, aqiq al-idm ma al-izb al-Shuy al-Sdn (Beirut 1972); Fud Maar, al-izb al-Shuy al-Sdn naarhu amm intaara (Beirut 1971); Muammad Sulaymn, al-Yasr al-Sdn f Asharah awm 19541963 (Wd Madan 1971).

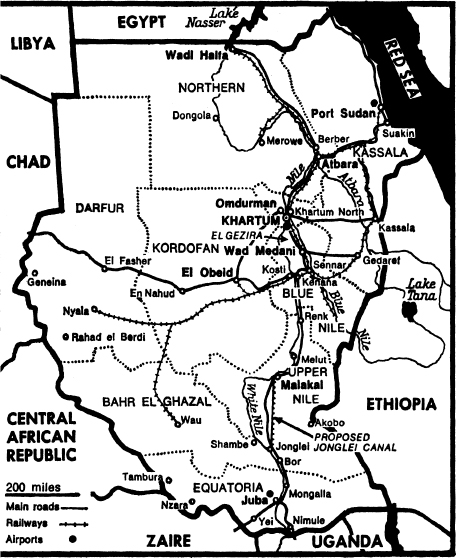

Sudan in the 18th and 19th centuries*

Prior to the Turco-Egyptian conquest in 182021, the Sudan was not a uniform political and governmental unit, and the rule of the Funj Sultanate, from its centre in Sennar, was rule in name alone. The centres of power that arose in various areas of the country were based on the tribal and religious structure prevailing in the country at that time. The exact number of Sudanese tribes during that period is not clear, but can be assumed to have been not less than the 572 tribes counted during the first census in 1956. Most of these tribes (representing approximately thirty per cent of the population) were in the South, and are, therefore, outside the framework of this study. In the area extending north of Bar al-Arab, the tribes were mostly composed of Arabic-speaking Muslims. However, even the population of that area was not homogeneous. Near the Egyptian border lived the Barbra-Nubian tribes, who spoke Nubian dialects in addition to Arabic. To the south of them, on both sides of the Nile, were a number of tribes related to the Jaaliyyn group. Although these tribes were largely Arabised and claimed a common forefather Jaal, a descendent of Abbs, uncle of the Prophet Muammad there is no doubt that their origin is Nubian. The most northern tribe of the Jaaliyyn is the Danqla, which inhabits the district of Dongola. The area south of them, near the bend of the Nile up to Ab amad, is inhabited by the Rubab and the Manr. One of the Jaaliyyn tribes, which occupies the area close to the junction of the Abar and the Nile, bears the name of the whole group. Within the Jaaliyyn, though not belonging to them, dwells the confederation of the Shyqiyya in the area between the fourth cataract of the Nile and al-Dabba to the north. All these tribes are

In order to complete this short survey of the northern tribes, three non-Arab tribal groups ought to be mentioned. Firstly, the Fr, founders of the sultanate of Drfr, in western Sudan, who, despite being Muslims, retain their own language up to the present day. The second group inhabits the hill region of south Kordofan, known as the Nuba mountains. The origins of the Nuba are not clear, but it is certain that they, in common with the Fr, found shelter in the hill region following the penetration of Arab tribes into the Sudan. These tribes speak various dialects and have for the most part retained their pagan beliefs into the twentieth century. The third group, also living in a hill region, are the Beja of the Red Sea Mountains whose origin is Hamitic. As with the Barbra in the North, the Beja have accepted Islam, and to some extent the Arabic language as well. The most Arabised of the Beja tribes are the Abbda, who control the Nubian desert pass between Egypt and the Sudan. The most famous and militant amongst the Beja are the Hadendowa, nomads inhabiting the southern area of the Red Sea Mountains up to the Abar River and the delta of the Gash. These tribal groups retained a great deal of independence, recognised even by the Funj sultans. The power of the tribes grew during the hundred years preceding the Turco-Egyptian conquest, as the central authority of the sultanate broke up. The supreme position attained by certain families, such as the Abdallb and the Ab Sinn in the Blue Nile region, has already been mentioned. Similarly, the confederation of the Shyqiyya was practically independent, while the Jaaliyyn created for themselves a political-religious centre in al-Dmir, at the junction of the Nile and the Abar. Funj rule in western Sudan, particularly amongst the nomad Baqqra and Kabbsh, was even more nominal, while the sultanate of Drfr had maintained an independent political status since 1596.