Acknowledgments

This book marks a departure from my usual research interests, which my historians instinct have kept focused on the early twentieth century. My turn to the current topic was dictated by world events. After September 11, Central Asia, perhaps one of the least-known regions of the world, found itself in the global limelight. I saw a need for a broad, accessible treatment of Islam in cotemporary Central Asia and put aside my other projects to write this book. This book was therefore written without the usual preliminaries of grant proposals and leaves from teaching, and thus owes more than usual to the help, advice, encouragement, support, and good humor of friends and colleagues.

Many individuals and groups heard excerpts from this book, but I owe a particular debt to Sergei Abashin, Laura Adams, Stphane Dudoignon, Adrienne Edgar, Marianne Kamp, Shoshana Keller, and Russell Zanca, who shared their insights and their own research with me. Grants from the National Council on Eurasian and Eastern European Research and Carleton College allowed a trip to the region in summer 2004. Many thanks for hospitality and guidance to Franz Wennberg and Muzaffar Olimov in Dushanbe and to Nurbulat Masanov in Almaty. I owe a great deal to many friends and acquaintances in Uzbekistan, who over the years have taught me a lot about Central Asia, but I think it prudent to leave them unnamed here.

I marvel at the luck that brought Shahzad Bashir to the small college where I teach and made him a colleague and a friend. In addition to providing support and encouragement, he read the whole manuscript as it progressed. Fran Hirsch read an almost complete version of the manuscript. Muriel Atkin, Daniel Brower, and one other referee who chose to remain anonymous evaluated the manuscript for the University of California Press. Their advice and criticisms made this a better book. I have not been able to use all the advice I received, but I hope that the finished book does not disappoint those who gave of their time and energy.

Working with the University of California Press has been a pleasure. Lynne Witheys enthusiasm for the project from the outset was crucial. Without Monica McCormick and Reed Malcolm, the process of completing the book would have been longer and unhappier.

Haroun and Leila have lived with this manuscript for large chunks of their lives; they will be even happier than I am to have it out of the way. Cheryl Duncan first suggested that I write this book. She has read every word of it, many times over, and given criticism and encouragement in equal measure as it has progressedall this on top of her abundant supply of love and care. It is to her that I dedicate this book.

St. Paul, Minnesota

October 31, 2005

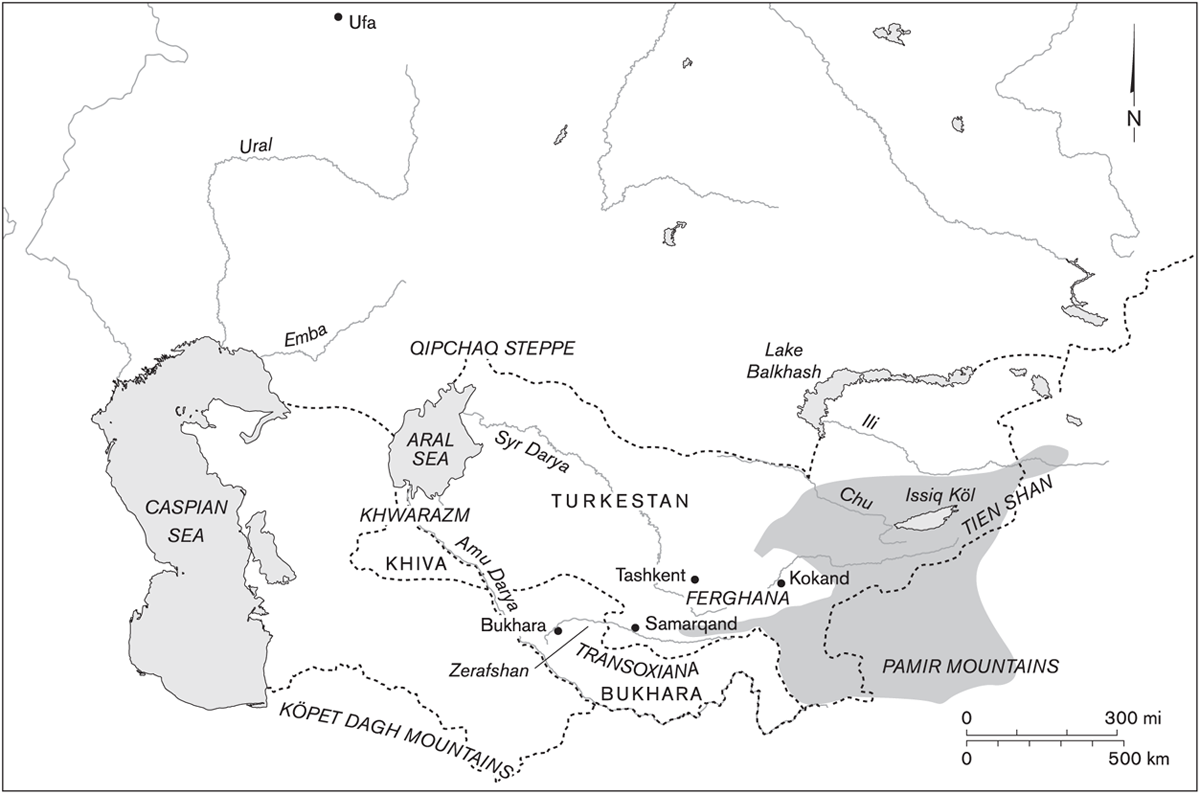

MAP 1. Central Asia: political boundaries in the tsarist period.

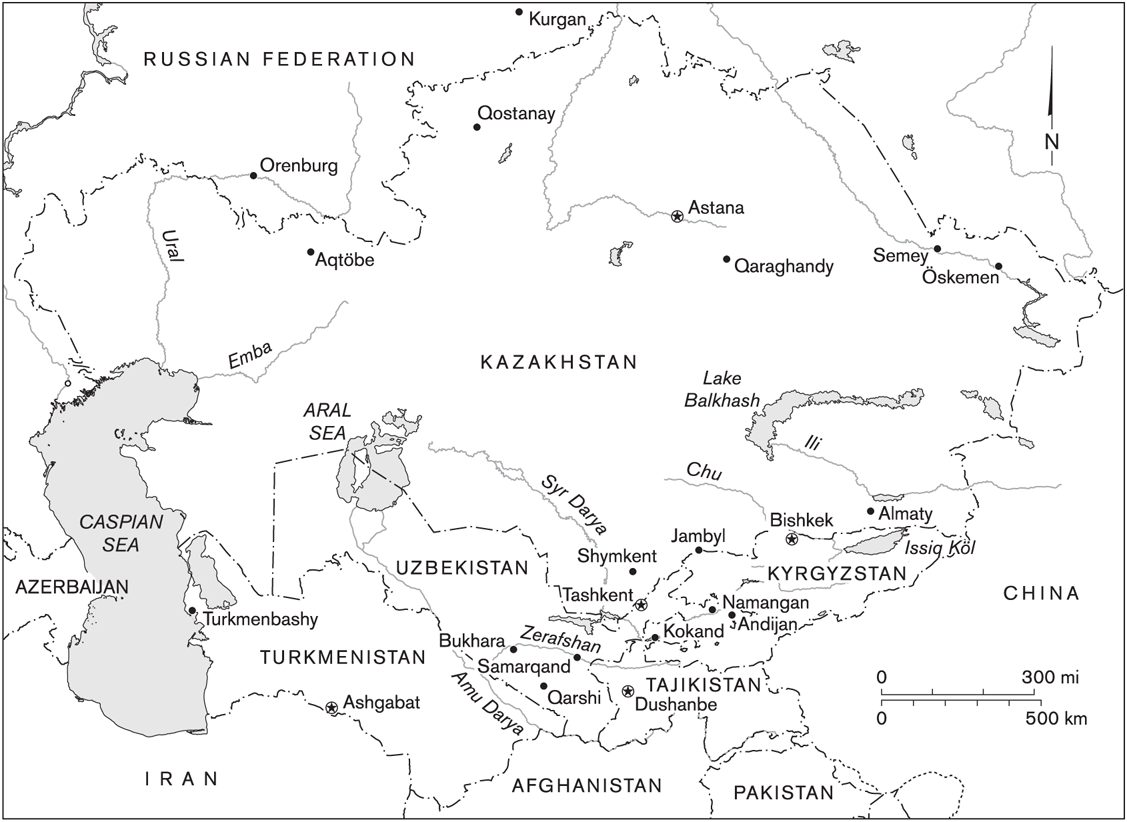

MAP 2. Central Asia: current political boundaries.

MAP 3. Tajikistan and the Ferghana Valley.

Introduction

Waiting in line at a cafeteria in Tashkent one day in 1991, in the last months of the Soviet era, I fell into conversation with two men behind me. They were pleased to meet someone from the outside world, to which access had been so difficult until then, but they were especially delighted by the fact that their interlocutor was Muslim. My turn in line eventually came, and I sat down in a corner to eat. A few minutes later, my new acquaintances joined me unbidden at my table, armed with a bottle of vodka, and proceeded to propose a toast to meeting a fellow Muslim from abroad. Their delight at meeting me was sincere, and they were completely unself-conscious about the oddity of lubricating the celebration of our acquaintance with copious quantities of alcohol.

This episode, unthinkable in the Muslim countries just a few hundred kilometers to the south, provides a powerful insight into the place of Islam in Central Asian societies at the end of the Soviet period. Clearly, being Muslim meant something very specific to my friends. Seven decades of Soviet rule had given Central Asians a unique understanding of Islam and of being Muslim. Islam after Communism had its peculiarities.

A few months after my encounter, the Soviet Union ceased to exist, and the republics of Central Asia became independent states. As old barrierspolitical, ideological, personalcame down, the region experienced a considerable Islamic revival. Mosques were reopened, new ones built, links with Muslims outside the Soviet Union revived. Islam has indeed experienced a rebirth in the region.

For many, especially in the West, this return of Islam boded ill. According to this view, Central Asia would become another hotbed of Islamic fundamentalism, a breeding ground of terrorismessentially a natural extension of Afghanistan and other anti-Western regimes in the Middle East. Westerners had reasons enough to fear this outcome. In November 1991, demonstrators in the Uzbek city of Namangan besieged the countrys president and demanded that he declare Uzbekistan an Islamic republic. In neighboring Tajikistan, independence degenerated into a bloody civil war that was widely seen as pitting resurgent Islamists against the incumbent Communists. By the late 1990s, militant organizations had emerged in Uzbekistan that sought the overthrow of the regime there and its replacement by an Islamic state. The Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), the most prominent of these organizations, developed links with militant groups in war-torn Afghanistan, and its members fought alongside the Taliban during the American invasion in the autumn of 2001. For many observers, the IMU represents the future of Islam in the regiona natural culmination of the rebirth of Islam. This view is based on certain assumptions, often unstated by its proponents, about Islam itself. According to this view, Islam is inherently political and naturally leads to anti-Western militancy. For this reason, the seventy years of Soviet rule were of no consequence, for once Islam reemerged, the paths to its politicization and militarization were foretold.