Campaign 23

Khartoum 1885

General Gordons last stand

Donald Featherstone

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

THE RISE OF THE MAHDI IN THE SUDAN

The two campaigns fought by the British in the Sudan, in 18845and 18968, were far more than an attempt to relieve Khartoum and the eventual reconquest of the country. For almost two decades Great Britain had been involved, directly and indirectly, in the military affairs of the Sudan, whose history during the late 19th century can be divided into four distinct periods:

1881-8 The rise and defeat of Mahdism

1881-3 The defeat of the Egyptian Army

1884-5 The first British involvement

1896-8 The reconquest of the Sudan.

The Sudan

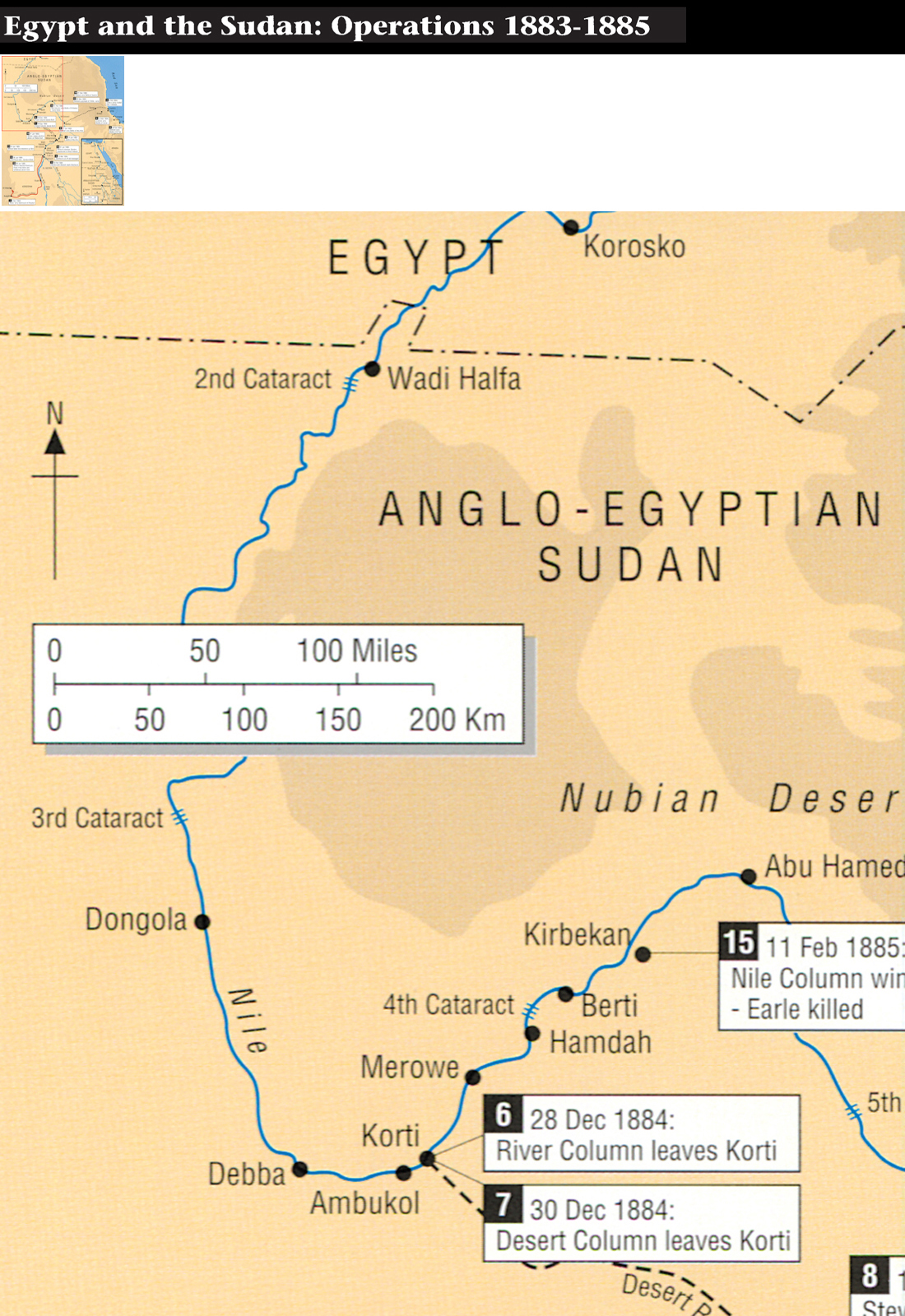

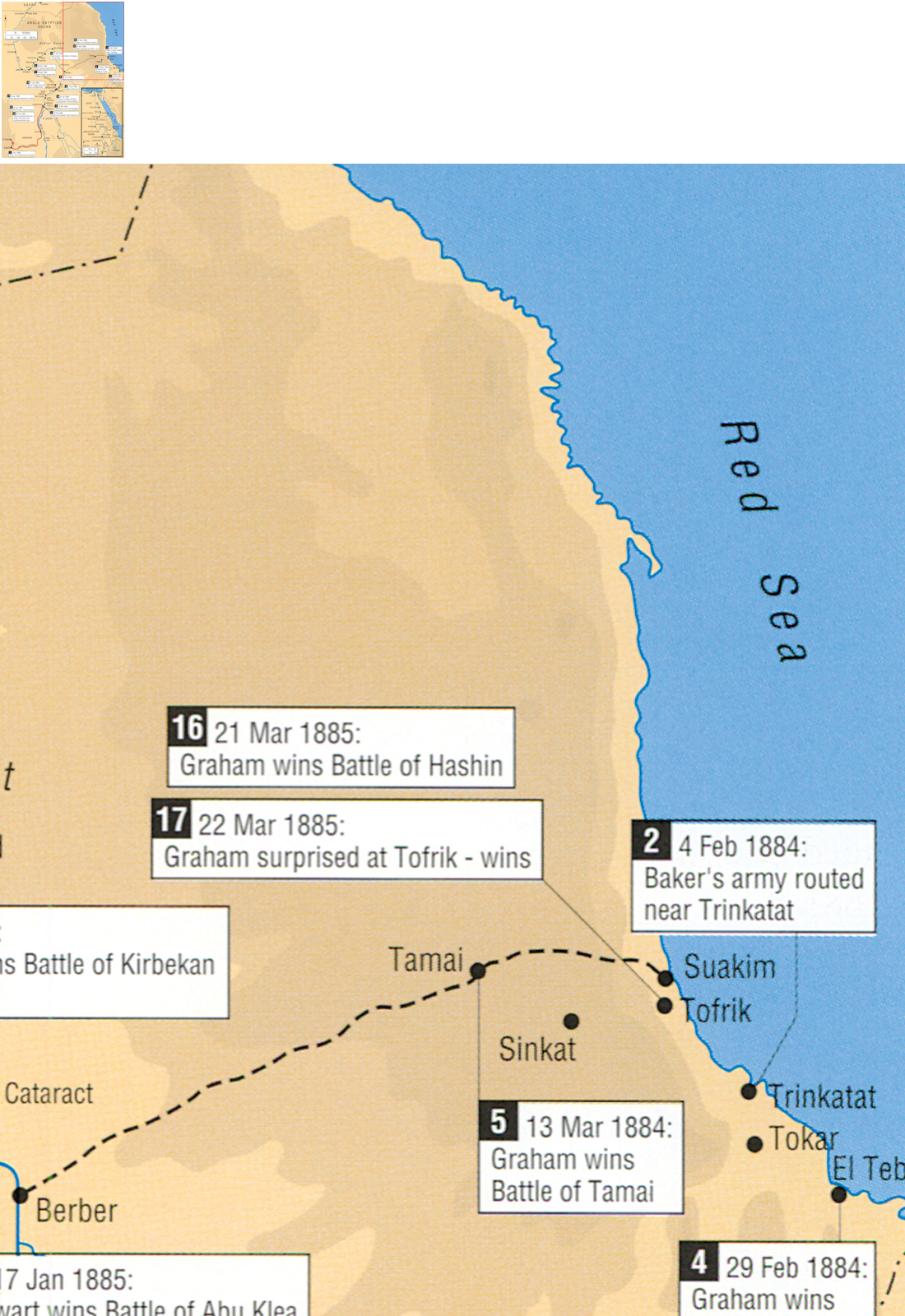

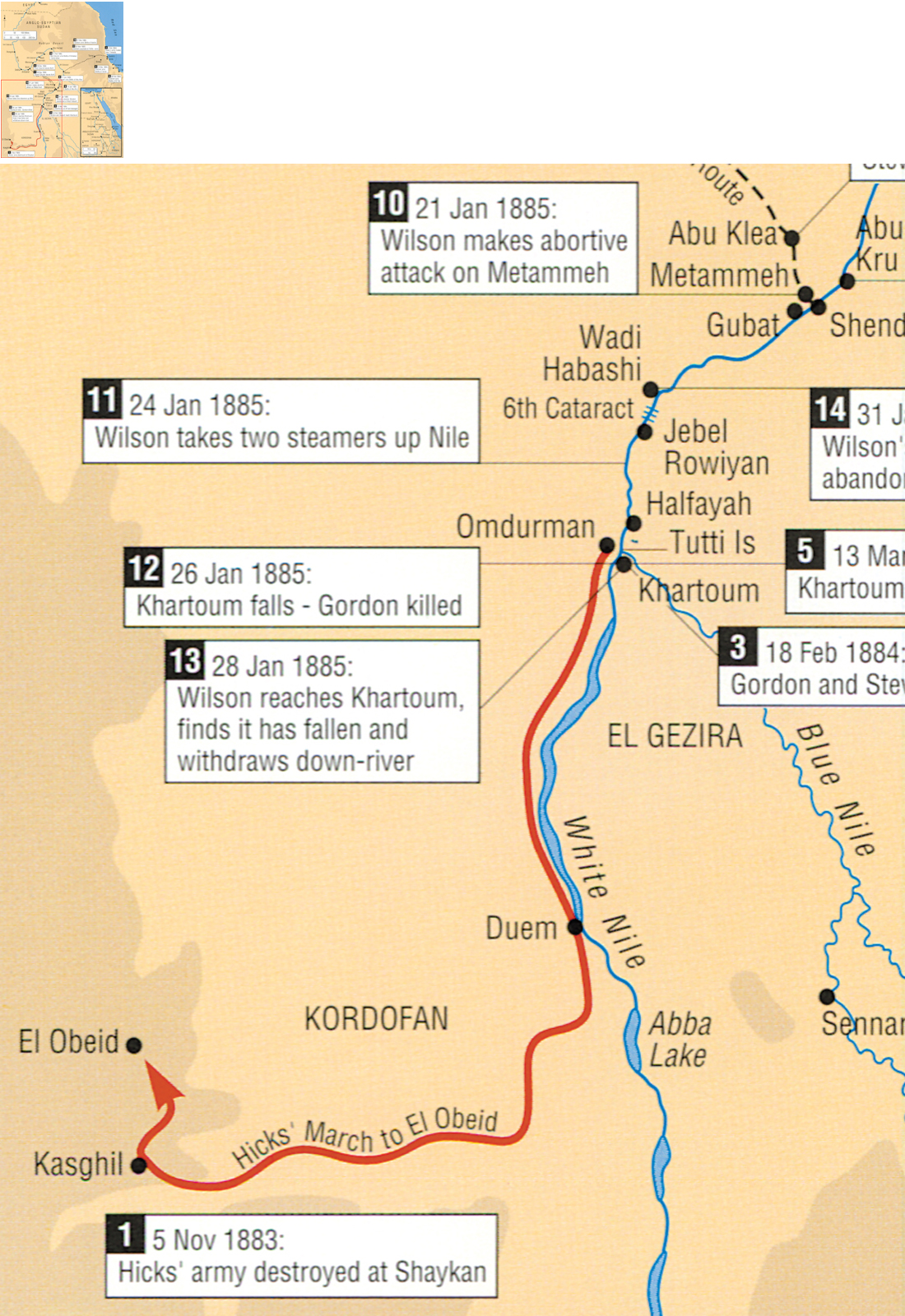

The Arabic name for the Sudan is Baled-el-Sudan Land of the Blacks, and the events under consideration occurred in the eastern (Anglo-Egyptian) part of the country, stretching about 1,400 miles from the southern frontiers of Egypt to Uganda and the Congo (now Zaire), and from the Red Sea to Wadia. The capital is now Khartoum, although after its capture by the Mahdi in 1885, the distinction of being the principal city was transferred to Omdurman. The northern part of the area is very arid, consisting mostly of scrub desert, rocky outcroppings and wadis, with large areas of sava grass; trees are mostly thorny acacia, and mimosa grows in close profusion. The southern part is scrub jungle and swampland. The most important feature of the Sudan is the mighty and dangerous River Nile, with six almost impassable cataracts between Egypt and Khartoum. Generally very hot, the climate is perverse and temperatures can drop to freezing during the night.

The Peoples of the Sudan

In the north the Hamitic Arabs, in the south the Negroes; the former being divided into several major peoples Beja in the area around Suakim; Ababdeha in the north; Bisharin south of Wadi Haifa; north of Debba the Kababish, the Hassaniyeh and the Shaguyeh near Khartoum. South of that city was the homeland of the Baggara people, and the Amara were the major tribe near Abu Hamed.

All of these were subdivided into numerous tribes the Hadendowa were part of the Beja, and the Taaisha were a division of the Baggara: there were the Beja-Hadendowa, Baggara-Taaisha, the Jaalin, the Danaqla, the Batashin, Berberin, Barabra, Allanga, Duguaim, Kenana, Awadiyeh, the Hamr-Kordofan, Darfureh, Monassir, Sowarab, the Hauhau-hin, Robatab, Base and Shukreeyeh. It could truly be said that the Mahdis recruiting ground was the entire male population of the Sudan.

History of the Sudan in the late 19th Century

This vast and inhospitable land, grudgingly watered by the Nile, had lain festering throughout the century, under the unchallenged, unkindly, unprofitable and unwise rule of her neighbour Egypt. In eight major garrisons and many lesser posts, 40,000 soldiers of the Egyptian Army held the country in corrupt and unhappy submission, stoking up fires of hatred that would inevitably burst into blazing rebellion. Early in 1881 the general unrest began to crystallize around the name of an obscure man of religion, Mohammed Ibn Ahmed el-Sayyid Abdullah, in his retreat on the island of Abba in the Nile, about 150 miles upstream from Khartoum.

Proclaiming himself the long-expected Mahdi, the Guided One of the Prophet, he preached that the Sudan was to be purged of its Egyptian oppressors, and her people brought back to the purity of the true faith. Soon, the Egyptian government, installed by the British after the Arabi Pasha revolt of 1882, found itself hard-pressed to maintain authority in the Sudan, being forced into a series of abortive operations against the Mahdis swelling hordes of followers until finding itself with only token garrisons to defend isolated posts at Sennar, Tokar, Donagla and Berber.

The Mahdi (Mohammed Ibn Ahmed el-Sayyid Abdullah), 1844-85. This warrior-priest of humble origin emerged in 1881, rapidly to become the undisputed leader of the entire Sudan, revered by all as a reincarnation of the Prophet. Before he died on 22 June 1885 (probably of typhus or smallpox) he had defeated every British and Egyptian challenge and had reigned supreme in the Sudan.

The Mahdis first battle victory was in August 1881 at Abba, where his 311 ill-armed Arabs cut a much larger Egyptian force to pieces; in October Rashid Bey marched to Khur Maraj with 1,200 men, to be annihilated by a force swollen to 8,000 warriors; on 29 May 1882 another Egyptian army, lured into the interior to Jebel Jarrada, were destroyed in their zareba at night by a Mahdist army now 15,000 strong.

The next objective was El Obeid, rich capital of Kordofan, defended by 6,000 Egyptian troops whose commander, Mohammed Sayyid, on 1 September 1882 hanged the Mahdis emissaries who had offered surrender terms. Now numbering 5,000 cavalry and 50,680 foot, the Mahdists assaulted the town but were thrown back with heavy losses by the disciplined fire of Egyptian Regulars Remington rifles. Abandoning former edicts that his troops should use only traditional weapons such as spears and swords, the Mahdi, now allowing the use of the rifles captured from previously defeated Egyptians, tightened the siege and El Obeid fell on 17 January 1883; high-ranking officers were executed and all the surviving troops were pressed into the Mahdis service.

Every reverse encouraged the rebellion which now turned into civil war, with followers flocking to the Mahdis banner; from Kordofan Province where his influence was greatest, the Mahdi extended his domains until he controlled most of western Sudan. At the same time his principal lieutenant, Osman Digna, was active among the tribes along the Red Sea coast, and by the autumn of 1883 several Egyptian garrisons were cut off and under siege.

The fall of Kordofan, the richest province in the Sudan, convinced the Egyptian government that an expedition would have to be sent to suppress the rebellion and, the British being unwilling to cooperate, sought a man to lead it. In late January 1883 Abd el Kader, the new Governor-General of the Sudan, appointed a retired Indian Army officer, Colonel William Hicks, to the post of Chief of Staff.

The Destruction of Hicks Pasha

Colonel William Hicks had begun service in 1849 in the Bombay Army, fought in the Mutiny of 1857, and saw service in Abyssinia with Napier in 1868. Courageous and energetic, but with little command experience, 52-year-old Hicks began organizing the troops available to him for his Sudan expedition. In April 1883 he led out a force of four and a half battalions of infantry, some mounted Sudanese Bashi Bazouk mercenaries and four Nordenfelt machine-guns. On 29 April, at Jebel Ain, he was confronted by a sizeable Mahdist force with numerous cavalry. In square, with rocket tubes, howitzers and the Nordenfelts pouring out a deadly fire at close range, they repelled the attack at a cost of only seven casualties; the enemy leaving more than 500 dead on the ground, including twelve Amirs and their leading chief, Amr-el-Makachef.