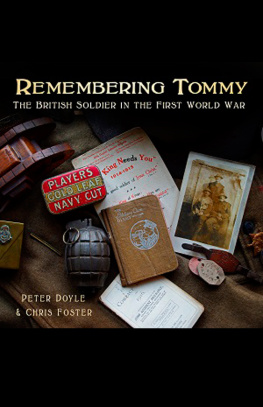

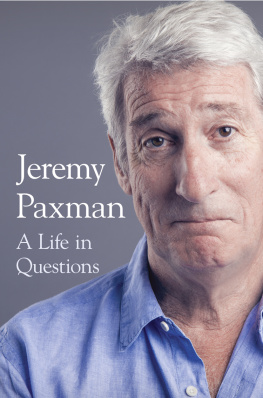

Uncle Charlie and his friends. They had no idea what modern war would be like.

There is a photo on the wall. It was taken, most probably, in the spring of 1915, and shows eight uniformed men in the jaunty confidence of youth, bedrolls slung over their shoulders. They stand, arms around each others shoulders, caps askew, one with a cigarette in his mouth, another with a pipe. They smile cheerily. The bright spring sunshine leaves deep shadows on their foreheads. In the middle, arms folded, a young man with a heavy moustache leans on a roadsign: DANGEROUS! KEEP OFF THE TAR. This is my great-uncle Charlie. He has a Red Cross badge on each shoulder and grins broadly.

In his entire military career Uncle Charlie won no medals for bravery, never advanced beyond the most junior rank in the army and almost certainly neither killed nor wounded a single German. He had enlisted in the Royal Army Medical Corps and his job was to save lives, not to take them. The 1911 census records Charles Edmund Dickson as a twenty-year-old living in Shipley, working as a weaving overlooker in one of west Yorkshires numerous textile factories. Uncle Charlie looks a slightly unconvincing soldier, cutting none of the elegant dash of glamorous young officers like Rupert Brooke. He fills the uniform, for sure. In fact, he looks as if, with a bit of time, he could more than fill it.

On 7 August 1915 this bright young Yorkshireman, with his affable, cheery face, was killed in Turkey.

Uncle Charlies is one of 21,000 names carved around the Helles Memorial, a great stone obelisk at the tip of the Gallipoli peninsula in Turkey, surrounded by fields of grain nodding in the breeze off the sea, and clearly visible to the boats that run up and down the coast from the Aegean to Istanbul. He was my mothers fathers younger brother, dead well before she was born. Yet as children we were all familiar with him seventy or more years later Uncle Charlie was a present absence. I often meant to ask my mother what she knew of how he had died, but I never did, and now shes dead I never will. Family legend had it that he signed up in the rush of naive, enthusiastic young recruits in 1914. Like most men of his background, he had almost certainly never been abroad before he travelled to his death on the far side of Europe.

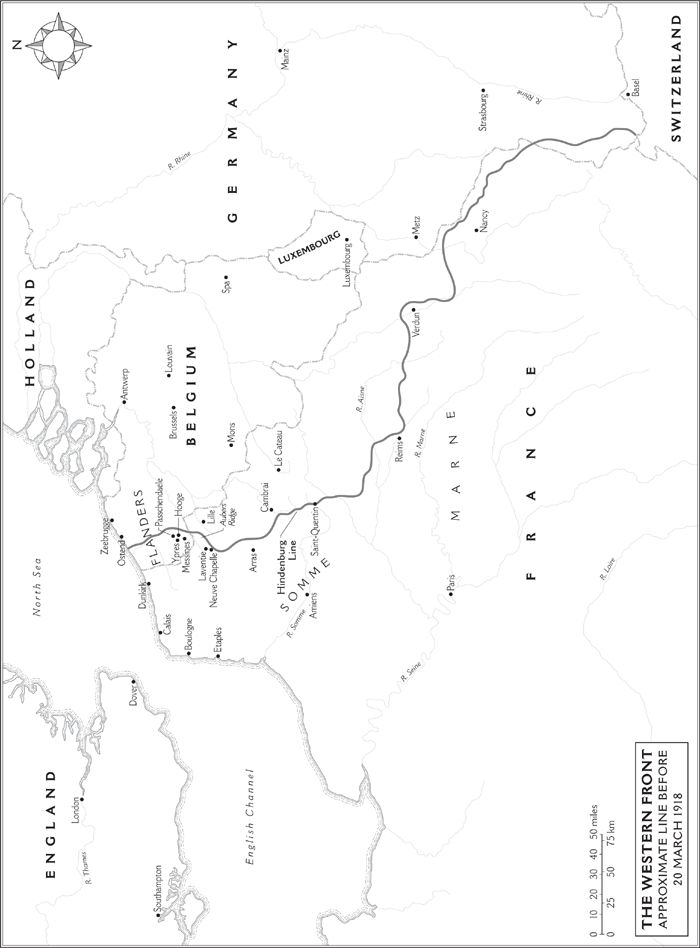

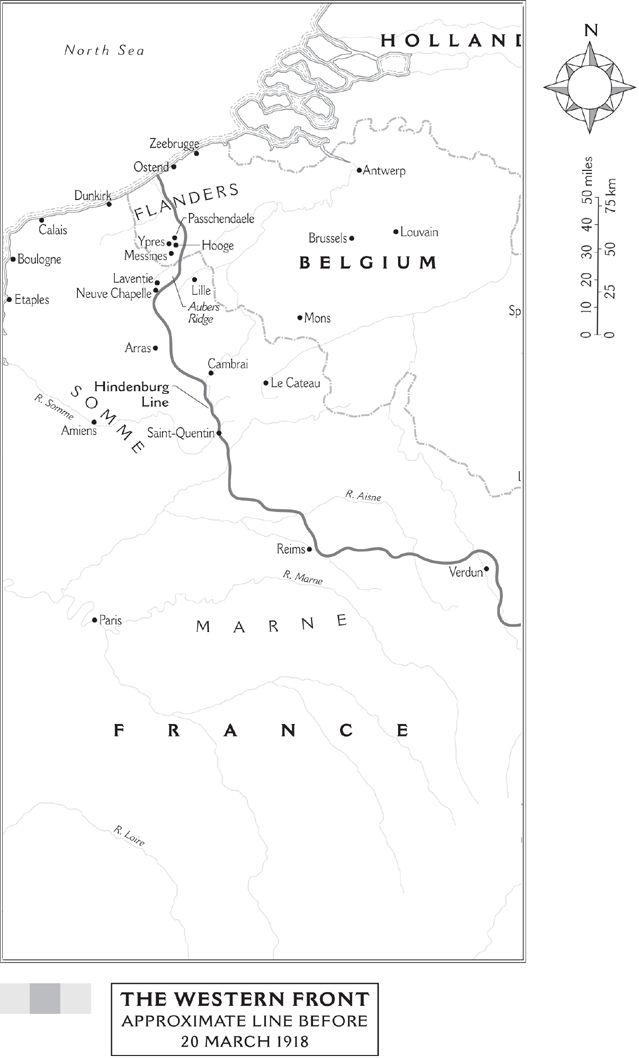

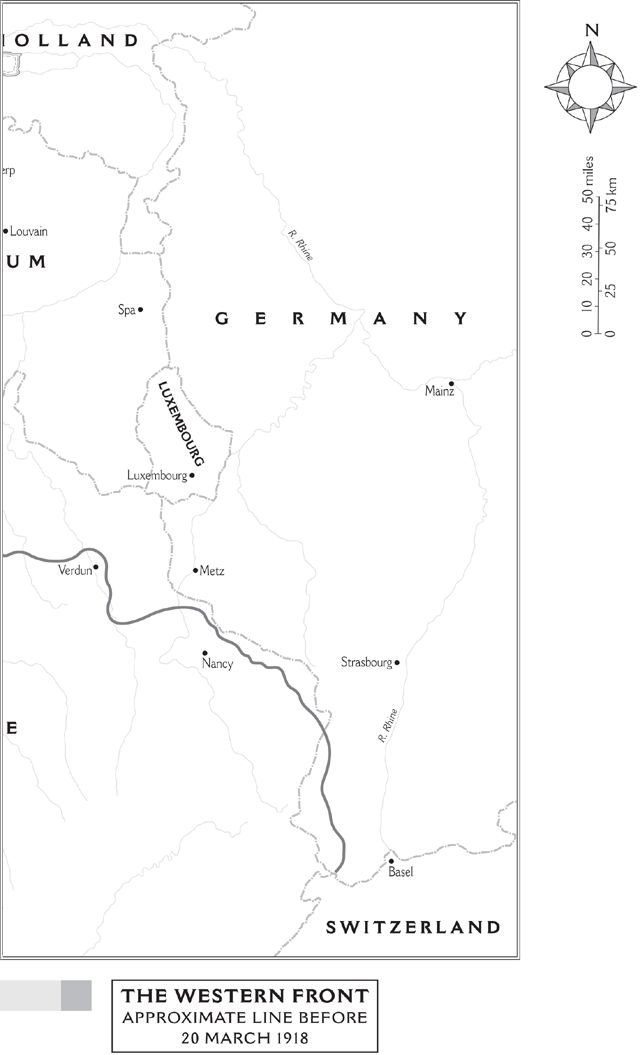

How exactly he died may never be known, but the causes and circumstances of his death are easier to explain. His detachment of the Royal Army Medical Corps had been despatched to Gallipoli as part of First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchills ill-conceived attack on the soft underbelly of the enemy, its purpose being to relieve the stagnation of trench warfare in France and offer a decisive breakthrough. Clement Attlee, the 1945 Labour Prime Minister, once told Churchill that his Dardanelles adventure was had been for the Royal Navy to blast their way through the Dardanelles, the narrow strait that leads to Constantinople (as Istanbul was then called) and, by attacking Germanys ally, Turkey, to open a new front in the war. When the navy discovered that Turkish mines and well-positioned shore artillery made it impossible to force the strait, British generals compounded the disaster by putting tens of thousands of men ashore in an attempt to destroy the Turkish batteries and safeguard the sea passage from the land. They had underestimated both the difficulty of the terrain and the quality of the Turkish army: British and allied soldiers had to fight their way out of the sea and then scale cliffs and hillsides in the face of well-established Turkish machine-gun positions. After the best part of a year of misery British commanders admitted defeat. Captain Attlee was one of the officers in charge of the evacuation of the peninsula: the retreat from Gallipoli was the only successful part of the entire operation.

The family never learned precisely what killed Uncle Charlie. Was he machine-gunned to death? Was he one of the thousands who had been weakened by the dysentery and typhoid that quickly spread among the men, pinned down in disgusting conditions in the gullies below the enemy machine guns for days on end? The memory of some others who died there bakers sons from the Orkneys; gardeners and footmen from the royal estate at Sandringham; the almost 500 men of the Dublin Fusiliers; or the son of the vicar of Deal who won the Victoria Cross for repeatedly wading ashore under fire to rescue wounded men from the beaches has been kept more conscientiously alive. The deaths of over 11,000 Australian and New Zealand soldiers at Gallipoli are venerated as a sacred part of their nations histories.

All I know about Uncle Charlie is contained in an old, brown, broken-sided cigar box found among my mothers effects when she died in 2009. She never smoked cigars, so presumably it was passed to her complete with most of its contents. Inside, at the top of the small bundle of documents and effects, was the paper every family dreaded to receive: Army Form B 104-82.

Uncle Charlie must have made it clear when he signed up that his mother, Florina, was a widow, for the printed Sir, with which the form begins, has been scored out and replaced with a handwritten Madam. The impersonal tone resumes with the printed sentence It is my painful duty to inform you that a report has this day been received from the War Office, notifying the death of , and here the colonel in charge of Medical Corps administration at Aldershot has inserted into the blank spaces Charlies name, rank and number, adding Number 34 Field Ambulance, of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force in the space left blank for his unit. The cause of death was , and here an entire line of the form is left empty, which the colonel has made no attempt to fill, just writing the single, unilluminating word wounds. Personal effects, the form states, will be sent on later.

Lying underneath it in the cigar box is another form, apparently signed by the War Secretary, Lord Kitchener:

The King commands me

To assure you of the true sympathy

Of His Majesty and The Queen