Table of Contents

Table of Figures

Foreword

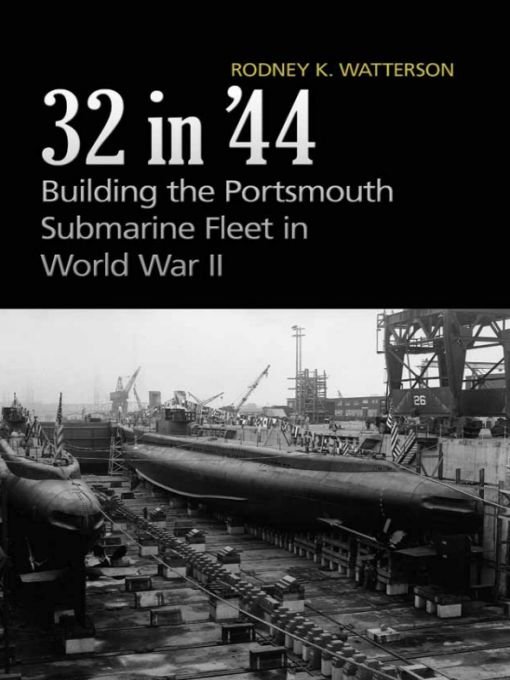

Naval ships have been built on the shores of the Piscataqua River since before 1776. When the U.S. Navy Yard was established in 1800, naval ship repair and construction commenced as an operation of the U.S. government. A century later, the United States began building submarines, and in 1914 the Portsmouth Navy Yard received an order for the L-8, the first submarine built at the yard. Three decades later the Portsmouth Navy Yard set the pace for submarine construction and played a crucial role in the buildup of the underwater Pacific fleet during World War II.

This book is the story of a remarkable period of submarine construction in the Portsmouth Navy Yard during World War II. Rodney Watterson examines the history of the yard, from the earliest period of submarine construction there through the era during which it was the principal submarine design and construction yard in the country. The shipbuilding efforts prior to World War II are well described and easily identifiable as the building bocks upon which the outstanding performance described in this book became possible. Probably the most noteworthy feature was that the Navy Department wanted to retain Navy control over the design and construction of submarines, largely due to the earlier dissatisfaction with private shipbuilding companies.

The Portsmouth Navy Yard was built on a small island in the Piscataqua River, thus the area and facilities for shipbuilding were very small, while the infrastructure required for large-scale construction was limited in scope. Additionally, the size of the labor force was very modest prior to World War II. Shipbuilders were not just brought in from the street; new employees required considerableoften very precisetraining in order to be effective contributors. These featuresinfrastructure, labor, and trainingall loomed as major impediments to a large-scale buildup of submarine construction.

Following World War I and through the late 1930s, funds for Navy ship construction, especially submarines, were extremely limited. Fortunately, and with apparent good foresight, the Navy Department was able to keep a very modest submarine construction workload ongoing at Portsmouth Navy Yard. During these several years many private shipyards were forced to close, and for those in any way involved with submarine construction, know-how was lost. There were several years when the only submarine construction ongoing in the United States was at the Portsmouth Navy Yard. As the 1930s drew to a close, the threat of war drove the need for the construction of new naval warships, including submarines. Elements of the Navy Department directed shipyards to identify needed upgrades of infrastructure, and large-scale improvements were rapidly undertaken.

The fact that a submarine construction effort at Portsmouth continued during the decades preceding World War II placed the yard in the enviable position of having a management team and a trained, skilled workforce in place. Both were critical to the yards many successes between 1941 and 1945. Indeed, the infrastructure, labor, and funding requirements were identified and Navy Department action was timely and responsive. The yard was able to proceed without impediment!

On the eve of the war, nearly four thousand people were on the payrolls at Portsmouth. Management realized, however, that far greater numbers were needed as new submarine orders poured in. Vast recruiting efforts were undertaken to increase the size of the workforce and improve training for new workers. As a result, by 1943 the number of men and women employed by the yard had swelled to more than twenty thousand.

During the early 1940s the Navy Department consolidated two of its existing bureaus into a single Bureau of Ships in an effort to eliminate the fragmentation of responsibilities. This new bureau was overwhelmed with its task of bringing new shipyards into the building business throughout the country. The impact on Portsmouth Navy Yard was most favorable. It was in the enviable position of not being overly managed by higher authority, thereby permitting many innovations by the challenged shipyard team. Many of these innovations are described in this book and, in some cases, are shown to be way ahead of their time.

Prior to World War II, the lifeblood of Portsmouth Navy Yard was its people. The managers and the workforce were made up of very experienced individuals, many of whom had stayed in their positions for lengthy periods of time. These individuals, in addition to supervising necessary training programs, were the ones who came forth with the ideas, challenges, and processes that led the yard to greater and greater performance. The yard was truly blessed with the caliber of its top leadership, both military and civilian.

In the concluding part of the book the author states, in part, that remarkable production success can be achieved when bold and enlightened management leads dedicated and motivated employees and both are zealously committed to a common objective. Such was the case in the astonishing performance of Portsmouth Navy Yards submarine construction throughout World War II, especially the thirty-two boats delivered there in 1944.

WILLIAM D. McDONOUGH,

Captain, U.S. Navy (Ret.)

Commander, Portsmouth Naval Shipyard

August 1974August 1979

Acknowledgments

I want to thank the members of my dissertation committee who got me started on this work while I was a doctoral student at the University of New Hampshire. These include my dissertation adviser, Kurk Dorsey, and committee members Jeffrey Bolster, Ellen Fitzpatrick, Gary Weir, and Carole Barnett. Their comments were extensive, insightful, and helpful. Also to be thanked are Richard Winslow, author of several Portsmouth Naval Shipyard histories, and Jim Dolph, the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard historian, who read the dissertation and provided valuable comments. Thanks to Capt. Bill McDonough, USN (Ret.), for writing the foreword. I especially want to recognize the important contribution of Cdr. Vic Peters, USN (Ret.). He made many valuable professional and editorial recommendations that significantly improved the final manuscript. Finally, sincere thanks to copy editor Julie Kimmel.

Many contributed to the success of my research. Archivist Joanie Gearin was especially helpful in finding Portsmouth Navy Yard records and managing the carts of boxes and binders that I mined during my many visits to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Waltham, Massachusetts. Archivist Patrick Osborne provided the same support at NARA in College Park, Maryland. Nancy Mason, special collections assistant at the Milne Special Collections and Archives at the University of New Hampshire, was especially helpful in reproducing the shipyard photographs used in the dissertation. Thanks also to Tom Hardiman, the keeper at the Portsmouth Athenaeum, for making available the oral histories of shipyard workers collected as part of the Music Hall Shipyard Project. Walter Ross, William Tebo, and Dennis OKeeffe were particularly accommodating, hospitable, and entertaining during my visits to the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard Museum.

Im especially grateful for the individuals who consented to be interviewed for this work. The interviews with Frederick White, Percy Whitney, William Tebo, Eileen Dondero Foley, and Dan MacIsaac gave meaning and life to thousands of pages of yellowed paper and hundreds of old photographs. Their contributions added greatly to the quality of the book.