Dedication

FOR CATHY

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the staff at the National Archives of Scotland; the Police Museum in Glasgow; and my wife, Cathy, for all their help and support in the writing of this book.

A great city with a strong leaven of scoundralism in its population.

Glasgow Herald, 7 October 1850

Preface

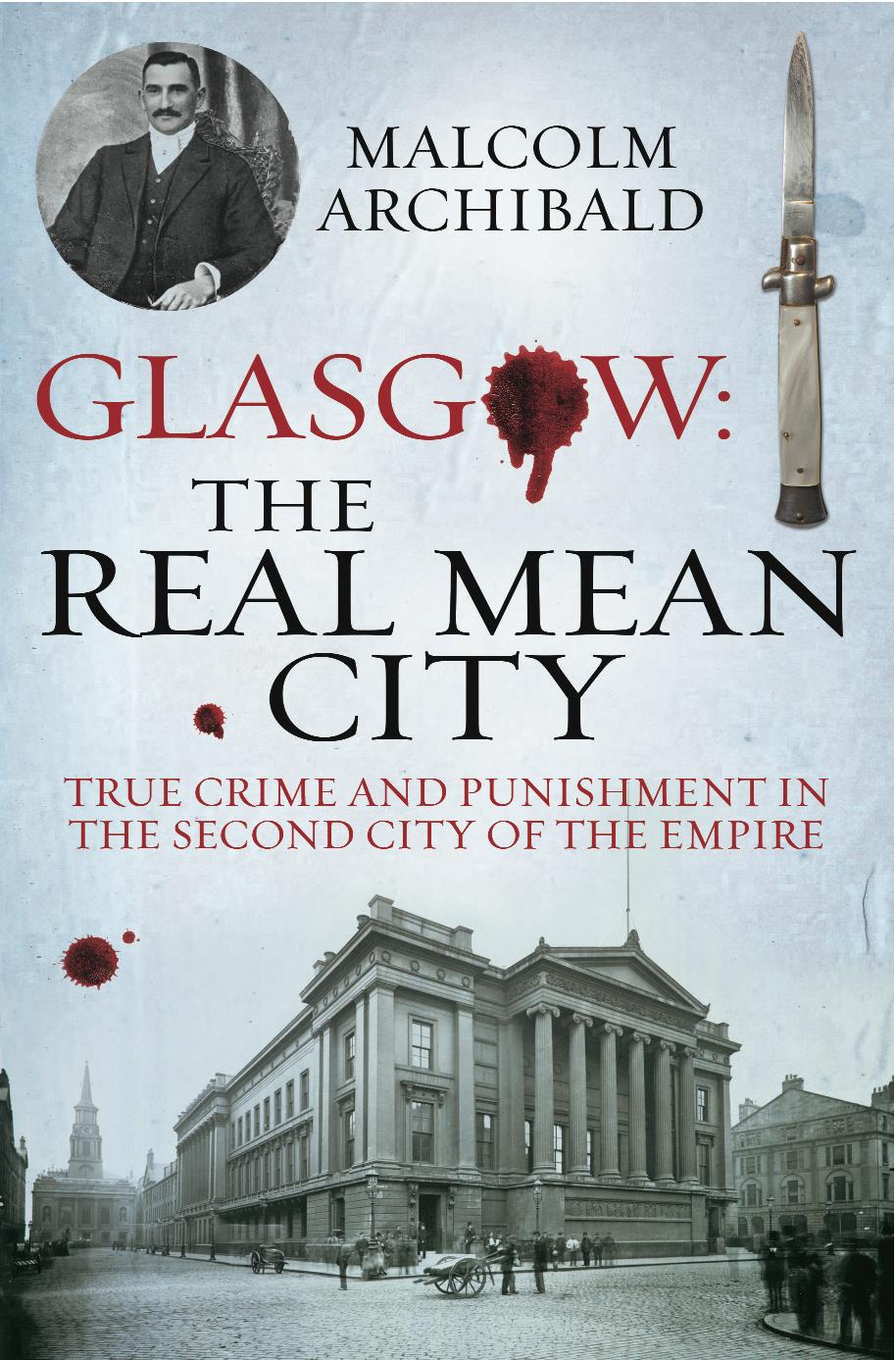

My grandfather, George Frederick Archibald, was a regular soldier. He joined the Royal Scots in 1897, aged 19, and left in 1919. During these twenty-two years, the world changed forever. He served in India, Burma and Ireland and throughout the First World War from Mons until the Armistice, and survived with a chest full of medals, lungs full of gas and a head full of stories with which he tantalised young grandchildren. Among the well-known tales such as The Angel of Mons, The Christmas of 1914, Ladies from Hell and The Crucified Canadian were many I have never seen written in any book about the Great War. Two of these involved regiments from Glasgow.

The first anecdote was of a time when a staff officer visited the trenches and saw a handful of Glasgow soldiers escorting a large number of German prisoners to the back areas. The officer was horrified to see that many of the Germans had broken noses and bruised faces. He accused the Glasgow men of abusing the Germans after capture. My grandfather, a CSM at the time, informed him gently that in hand-to-hand combat this particular regiment sharpened the rim of their steel helmet and used it as a weapon: a trench-warfare Glasgow kiss. The second story was similar; he told me of having served alongside a regiment of Glasgow Bantams, men under five feet in height who had the reputation of having disposed of more of the enemy by the bayonet than by the bullet.

As a long-eared child with all a boys interest in the gore and supposed glory of warfare, I lapped up these tales and often wondered what sort of men these Glaswegians were. I did not know then that Glasgow contributed an estimated 200,000 men to the British Army in that horrendous mass slaughter, or that in 1914 Glasgow reputedly built more ships than all of Germany or the United States of America. I was later to hear of the landlords who tried to evict women while their men were fighting in France, leading to the largest rent strike in British history and proving that Glaswegian women were every bit as formidable as their men. Much later, I read about Red Clydeside and a British government so afraid of supposed Glaswegian communism that it sent 10,000 English troops backed by tanks and artillery to the city, while confining the local Highland Light Infantry to barracks in case it joined the strikers. I heard of the police baton charge in George Square that was repelled by strikers who were campaigning purely for decent working conditions. I learned of Glasgow gangs that fought with bayonets, and of razor gangs a thousand strong battling it out in the streets. In time, I also knew about the Orange Marches and the bitter rivalry between Celtic and Rangers, two of the most famous football teams anywhere.

The stories and legends, true, half-true and pure fiction, all painted a picture of a city that resounded with verve and violence, yet when I visited I found forthright, cheerful and friendly people who were more than willing to share all they had. I had read of a city of bleak black tenements and foul slums, but although there were bad areas in Glasgow, as in every city, there were also splendid museums and beautiful parks, and some of the Victorian buildings were of such high quality they would be an asset anywhere. There are churches by Greek Thomson, an Art School by Rennie Mackintosh, a City Chambers that would rival that of any city in the world and a number of quality universities. This city produced two British prime ministers and arguably Scotlands most controversial socialist in John Maclean; it built many of the Empires railway locomotives and a huge proportion of the words ships; it boasted the largest timber importing business in the world, as well as the artist Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Throughout the nineteenth century Glasgow was a beacon of progress, and there were probably more Gaelic speakers here than in any other city in the world there were many sides to Glasgow. And yet the legends of crime and violence persisted. I wondered what had created this negative image of Glasgow and when it had earned its reputation as a grim dark place.

The answer does not lie very far back in time; it was the nineteenth century that saw Glasgow flourish as Scotlands largest city and fostered Glasgows multi-faceted reputation for culture, progress, engineering and crime. This book will not attempt to write a history of Glasgow; far better qualified historians than I have done and will continue to do that. Instead, I will attempt to draw a picture of the criminal side of Glasgow in the nineteenth century not only the obvious crimes of robbery, assault and brutal murders but also the more unusual, the fraudsters and child strippers and ship scuttlers, who all added to the overall pattern of crime.

The book starts with a brief explanation of the creation of industrial cities and the fear of crime they instigated, followed by a look at Glasgow itself. The bulk of the book consists of thematic chapters that cover the whole spread of the century. As it is impossible to cover even a fraction of the crime that occurred with a major city over this time period, what is mentioned is merely a representation of events, but hopefully enough to capture the atmosphere of Glasgow in the nineteenth century. Within these pages is the dark side of the city, but even here there are the bright splurges of humour, stern courage and undoubted humanity that help make Glasgow the great city it undoubtedly is.

Victorian Cities, Glasgow and Crime

When the English gentleman Edmund Burt visited Glasgow in 1730 he thought it the prettiest and most uniform town that I ever saw and I believe there is nothing like it in Britain. In 1772 the Welsh naturalist Thomas Pennant thought Glasgow the best built of any second-rate city I ever saw. These were only two of the travellers who gave favourable comments on Glasgow when the town had not yet mushroomed. Glasgow had been a quiet city that languished on the banks of the Clyde, always important but never quite central until eighteenth-century trade and nineteenth-century industry catapulted it into Scotlands largest city, the second largest city in Great Britain, the Second City of the Empire and the greatest shipbuilding centre the world had ever seen.

Glasgows position on the West Coast of Scotland gave certain advantages with trade to North America during the troubled eighteenth century. It was distant from the main bases of the French privateers that wreaked havoc with English and East Coast Scottish shipping, and it was free of the tides and winds of what was then termed the British Channel, thus making the transatlantic passage less hazardous. Geography ensured the passage would take less time from the Clyde than either the Thames or the Severn. When the Glasgow merchants used these advantages and added kinship connections with the smaller tobacco plantations in North America, they began to create vast commercial fortunes; history remembers them as the Tobacco Lords.

The tobacco trade between Scotland and the North American colonies had begun in the seventeenth century but escalated after 1707 when Scotland united her parliament with that of England to form Great Britain. Within a few decades Glasgow overtook Bristol and Liverpool in the transatlantic trade and used the wealth to create industries and deepen the Clyde so shipping could penetrate upriver as far as the Broomielaw. Although the American War of Independence severely damaged the tobacco trade, by then Glasgows industry was well established and the city grew year on year. Glasgow was Scotlands boom town.