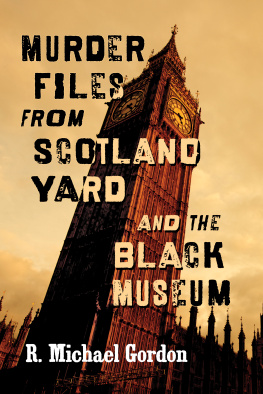

T he Black Museum officially came into being in 1875, when exhibits that had been acquired in previous years as evidence and produced in court in connection with various crimes (not just murder) were collected and displayed in a cellar at 1 Palace Place, Old Scotland Yard, Whitehall. It was dubbed the Black Museum by a newspaperman in 1877. Eight years later the augmented collection was moved to a small back room on the second floor of the offices of the Convict Supervision Department. By then, the objects on display, consisting mainly of weapons, and all carefully labelled, numbered about 150.

In 1890, when the Metropolitan Police began moving into their new headquarters at New Scotland Yard, between Whitehall and the Victoria Embankment, the Museum went too. Now called the Police Museum, its primary object was to provide some lessons in criminology for young policemen, and secondly to act as a repository for artefacts associated with celebrated crimes and notorious criminals. Privileged visitors, criminologists, lawyers and people working with the police were shown round the Museum by a curator, who for the last 100 years has always been a former policeman, with a special responsibility for the cataloguing, maintenance, collection and display of the exhibits, and for dealing with correspondence from criminologists and policemen all over the world.

In 1968, the Metropolitan Police moved into their present modern high-rise premises at 10 The Broadway, London SW1. The Museum, now officially designated the Crime Museum, was housed in a large room on the second floor. Eleven years later, on the 150th anniversary of the founding of the Metropolitan Police force, the Museum was reorganised, redesigned and resited on the first floor of the Yard, Room 101, and on 12 October 1981 it was officially reopened by the then Commissioner, Sir David McNee. Not open to the public, it can be visited by criminologists, distinguished persons and foreign visitors. But it is generally used as a teaching aid, and to acquaint serving policemen with some of the more sensational aspects and diversity of their job.

The Museums collection of articles, documents, photos and exhibits is unique. It covers more than murder. Other sections deal with Forgeries, Espionage, Drugs, Abortions, Offensive Weapons, House-breaking, Gaming, Bombs and Sieges, and Crime pre-1900. The Museum also contains displays concentrating on particular crimes, such as the Great Train Robbery and the attempted kidnapping of Princess Anne, and possesses such peculiar exhibits as Mata Haris visiting-card, a fake Cullinan diamond, a loving-cup made from a skull, two death masks of Heinrich Himmler, and 32 plaster casts of the heads of hanged men and women, executed in the first 70 years of the nineteenth century at Newgate Prison, and at Derby and at York. Some of these shaven heads are said to have been made to record the features of those who were hanged. Many criminals then used aliases, and the only way of identifying them, if necessary, after death (before the use of photographs and fingerprints) was to make a plaster likeness. Most of these heads were probably made for doctors or phrenologists intent on proving theories about the physiognomy of criminal types by examining the shape and every aspect of a criminals head after its owner was dead and gone.

Some items are not on show. There is a mass of other material (newspaper cuttings, photographs, documents, letters and miscellaneous artefacts) relating to the exhibits and to other crimes, which is kept in cupboards under lock and key, mainly because space is restricted, but also because some of the items, such as police photographs of mutilated murder victims, are too gruesome to be shown.

Those on display are grisly enough: a glass tank of formaldehyde containing a murderers severed arms; a skeletal hand; a pickled brain; and a grim assortment of instruments of death. Even innocuous household objects like a tin-opener, a cooking pot or a bath become more than sinister when you know how they were put to use. The total effect of the Museums exhibits and show-cases is cumulatively shocking. They present a dreadful picture of ruthlessness, cruelty, greed, envy, lust and hate, of mans inhumanity to man and especially to women. There is nothing of kindness or consideration. There is no nobility, save that of the policemen murdered on duty. There is no pity or mercy; there is pain and fear. But the Museum makes you realise what a policeman must endure in the course of his duty: what sights he sees, what dangers he faces, what depraved and evil people he has to face so that others may live secure.

This book covers a period of 150 years and contains murders investigated by the Metropolitan Police which were not included in my previous book, Murders of the Black Museum. Charles Peace and the murder of Arthur Dyson appeared in that book; but after it was originally published in 1982, a manuscript written by the investigating inspector was sent to me by one of his descendants and passed on to the Museum. This added so much new detail that Peaces story was rewritten and reappears here. Indeed, if any reader has any objects, documents, photographs relating to any of the murders described herein, the Museum would be glad to receive and preserve them.

The accounts of these murders have been dealt with as case histories, with an emphasis on factual, social and historical detail, and on the characters and background, so far as it is known, of both victim and murderer. Principal sources are listed at the back of the book. But in the main, statements to the police and to reporters, as well as court proceedings, have formed the basis for each account. No dialogue has been invented: it has been reproduced from statements and what was said in court by the accused, by witnesses, and by the judiciary and the police. The whole truth is of course never told in court, or revealed. In some respects a court of law is a theatre of deception, where the witnesses, defendants and barristers seek to deceive the jury and each other. All the relevant facts are seldom disclosed. Even the judge, the arbiter of truth, can mislead and be misled. That is why there is always some doubt, when motives and some matters are not fully explained or known, about even the most clear-cut evidence. This is the fascination of murder the wanting to know not just about what happened, about who and how, and where and when but why.